First Section

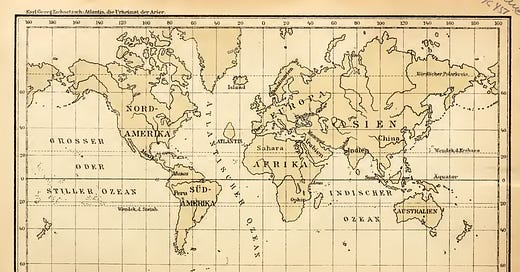

The original homeland of the blond, blue-eyed Aryan tribe, which is also generally known among us as the Germans, was the island of Atlantis, which sank into the sea due to the catastrophe known as the Sintslut and whose remains still rise above the Atlantic Ocean in the Azores islands.

Due to the location of the island of Atlantis between Europe and America, migrations took place not only to the former continent but also to America. The migrants then carried the ancient traditions concerning the events that had taken place on the island to the new lands, and there they continued to live on. To clarify the historical events on Atlantis, therefore, one must also consult the American traditions, which moreover reach back much further than the European ones and report on events that go far beyond the Sintbrand.

The European mythologies (legends, traditions) speak of four world ages called the golden, silver, bronze, and iron ages. However, these world ages only encompass the period between the Sintbrand and the Sintflut. The situation is different with the world ages mentioned in the American traditions. These span much longer periods than those mentioned in the European mythologies and cover time periods that were of the greatest significance for the fate of the Atlanteans, i.e., the Aryans, as they called themselves.

At the end of each of the first three world ages, the Aryans suffer a severe catastrophe. The sequence of the world ages is not entirely consistent in the American traditions. Since the last world age ends with the sinking of the island into the sea and the preceding one ends with a rain of fire, the two earlier world ages are left to be marked by destruction through famine and wind. Which of these was the first and which was the second world age is subject to disagreement in the traditions. The order given in the Codex Chimalpopoca—Sun of the Tigers or Hunger, Sun of the Wind, Sun of Fire, and Sun of Water—should, since the last two world ages are correctly indicated, also be regarded as correct for the order of the first two world ages.

The first world age (or sun) ends through famine, as an evil spirit tears up all the grass, all the flowers, and plants, thereby causing the death of mankind. This is the usual tradition. According to Gomara, the destruction is caused by earthquakes. In both versions of the myth, it is always the earth itself that, by withdrawing its benevolence, brings about the end of the first world age. Those who escaped the famine or the earthquake were eaten by tigers.

The second world age is that of wind or air. At the end of this world age, powerful hurricanes arose, uprooting trees, tearing houses and even rocks apart, and destroying mankind.

The third world age is that of fire. At the end of it, the god of fire descends to the earth to destroy it. Only the birds escape, and the people who had been transformed into birds. A single human couple hides in a cave.

The fourth world age is that of water. At the beginning of this period, the serpent-woman Cihuatcohuatl or Luetazli populated the earth. She always gave birth to twins. Therefore, she was later revered as the mother of the human race and as the protectress of children—indeed, as a goddess of the highest rank. At the end of this world age appeared the goddess of water, Matcacueje, the consort of the water god Tlalok, who destroyed the human race with a universal flood.

In the American tradition, the duration of the four great world ages is also specified, according to Humboldt’s determination, as 18,028 years. Furthermore, both in the American tradition and in that of the Egyptian priests, who shared information about it with the Greek sage Solon and later with the Greek historian Herodotus, chronological information has been preserved, according to which the sinking of the island of Atlantis, i.e., the Sintflut, occurred about 9,600 years before our calendar era; thus, a total time of 29,500 years from the beginning of the first world age to the present emerges. From this, it follows that the Aryans have known a reckoning of time for at least 29,500 years, if not longer, and thus lived in order and discipline.

While no detailed information is found in the traditions about the first two catastrophes—through famine and storm, which can therefore also be called Sintfamine and Sintstorm—quite precise traditions have been preserved about the two later catastrophes—through the fiery comet hail (Sintbrand) and through the sinking of the island into the sea (Sintslut)—as well as about the events in the intervening period, both in the Old World and in the New World.

Furthermore, in the various mythologies, besides information about the events in the time between the Sintbrand and the Sintflut, there are also references to the division of the land, the buildings, the customs and traditions, and other conditions in Atlantis. Given the significant gaps that exist in all mythologies, to create a coherent picture of Atlantis and the events and conditions there, one must compare the mythologies, assemble the relevant parts, and supplement them mutually.

Second Section

The hail of fire (Sintbrand), presumably caused by a comet that came too close to Earth, does not seem to have struck and devastated the entire island of Atlantis but only the southern part, which was also home to the fertile plain inhabited by the Aryans. Here, the Aryans had formed a large community. The northern uninhabited part, however, where the volcanoes were located and which was probably covered by dense primeval forests—hence it was not cultivated by the Aryans—was spared from or less affected by the world fire, so that animals survived there.

If the comet thus apparently only struck the southern half of Atlantis, then its main area of devastation must have extended further south from Atlantis. Due to Earth’s rotation, the comet must therefore also have touched regions southeast and southwest of Atlantis. South and southwest of Atlantis lies the Atlantic Ocean, where a fire would leave no traces. It is different with the lands lying south of the latitude and east of the longitude of the Azores—that is, mainly North Africa, including the Sahara and extending east to Arabia. In the Greek myth of Phaethon, it is also said that through the uncontrolled chariot of the sun, which the youthful, inexperienced Phaethon could no longer control, the Earth was set on fire. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book 2, line 40, it reads:

“Then first the people of Africa turned black,

their blood boiling through their pores;

then Libya’s fields turned into deserts,

where all moisture was devoured by the blaze.”

Other regions, such as Scythia, the Caucasus, the Alps, and others, are also mentioned, which were probably hardly damaged by the fire trail of the comet. The mention of all regions known to the ancients probably arose from the belief that the Sintbrand had destroyed the whole world. When the Aryans later arrived in North Africa, they still found traces of fire everywhere, from which they had to conclude that the world fire had been widespread. It is very likely that lands that were already not very rainy were transformed by such an immense fire, which destroyed all vegetation, into deserts that remained barren thereafter. That the Sahara was once more water-rich and thus more vegetated is shown by the numerous canyons once carved out by water and also by the fossilized tree remains that have been found in the Sahara region.

The comet therefore must have begun to touch the Earth much further east than the longitude of the Azores. The traditions give a fairly precise picture of the events during the Sintbrand. The hail of fire began at evening on the vernal equinox with such speed and violence that of the entire numerous Aryan tribe populating the plain, only three people—who happened to be near a spring (Urd well)—found refuge in a cave at the edge of this spring from destruction. These three were an already somewhat elderly man, his much younger sister, and her small daughter, who was about nine or at most twelve years old. The woman was so severely wounded that she died on the evening of the second day or in the night that followed.

As the traditions further relate, she gave birth while dying to a premature child, or rather, the child had to be cut from the mother’s womb by the man—an old man—who had also lost one eye during the Sintbrand. This child was a boy, born at seven months, and was cared for by the old man, who became his foster father, and by his little sister, who was first his foster mother and later his wife. The traditions do not agree on what animals provided the milk. Presumably, various animals had to nurse the child in succession—apparently a wolf or dog, then a wild goat and a deer; it seems that the wolf or dog fled into the life-saving cave along with the humans. Since the Aryans at that time were still vegetarians, the animals moved without fear near the humans. It therefore would not have been difficult for the old man to accustom some of the animals to give milk to the child.

That three people of the Aryan tribe survived the Sintbrand was due, apart from the protective cave, to the two springs that formed the well known as the Urd well in Norse mythology. Of these, one was ice-cold and the other hot; the first was presumably closer to the cave, while the hot spring lay closer to the Yggdrasil oak. The hot spring emitted strong vapors, which always kept the leaves of the Yggdrasil moist and which presumably enabled the Yggdrasil to withstand the fire of the world blaze. The cold spring, on the other hand, is credited with the fact that the water of the Urd well did not boil during the world fire; at the same time, the cool, rising water provided relief to the surviving humans and thus enabled them to endure the terrible fire that wiped out the entire remaining Aryan people.

Yggdrasil is referred to in Norse tradition as an ash tree; but that cannot be correct. “Dgg” or “Yg” corresponds to the Norse “Eg” and the English “oak,” and “Yggdra” or “Ygdra” corresponds to the Norse “Egetrae” and the English “oaktree,” while the ending “sil” is identical with “soul.” Yggdrasil would thus mean “oak tree of the soul,” or, since soul = life, also “oak tree of life” and therefore “tree of life.” The term “tree of life” indicates that this tree provided a nourishing fruit. Among oaks, there are several species that bear edible fruits. These fruits—acorns—can be eaten raw or roasted, or, as was the case in Atlantis, even used as bread flour. One of these species, which is evergreen, occurs both in Western Europe and in North Africa. This type of oak was probably the Yggdrasil, which was kept moist by the water vapors rising from the Urd well and thus escaped the world blaze. It remained green and fruit-bearing, and it was this tree that provided sustenance to the foster father and his young niece during that time.

Tree worship, which is found throughout the world, was therefore worship of the Yggdrasil, the tree of life. This tree was often represented by a simple cross symbol and in this form was worshipped in various parts of the world. The use of the cross itself was very widespread in ancient America; crosses or trees were planted on the graves of the dead, crosses were worn as amulets, and cross symbols protected against ghosts at night. The cross was also directly worshipped in some areas of America as the “tree of life.” The cross erected by Quekalcoatl or Huemac was revered as the god of rain or health and as the tree of sustenance or life. The swastika also represents the cross in Europe, Africa, Asia, and America.

The cult of springs, which was as widespread as the tree cult and often combined with it, can be traced back to the sacred Urd well, at which the Yggdrasil also stood. Associated with the Urd well is also the water baptism, which was found in various parts of the world. This practice also existed in ancient Germanic times. The water baptism probably goes back to the old Atlantean custom of sprinkling the newborn with the water of the sacred Urd well—with the water of life that once enlivened the first ancestors. In addition to a water baptism, there was also a fire baptism, in which the newborn was passed through fire. This custom also refers to the Sintbrand—the child was thereby to be protected against fire. The practice of newlyweds jumping over fire has the same meaning.

The Urd well is also related to the legend of the fountain of youth, or the rejuvenation fountain, which is also found in various parts of the world. For example, in the German heroic saga of Wolfdietrich, this fountain of youth appears. Wolfdietrich was led by the rough elf across the sea in a ship to a land (Troy), where she ruled as queen; there she bathed in a rejuvenation fountain, shed her rough skin, and emerged with the new name Sigeminne, as the most beautiful of all women. This land (Troy) is Atlantis, and the rejuvenation fountain is the Urd well. In the Edda it says: “This water is so holy that everything that comes into the well turns as white as the inner skin of an eggshell.” This is a common phenomenon often observed at hot springs, where objects placed in them become coated with a white sinter layer. In the Azores, there are still hot springs that deposit sinter.

Furthermore, the Urd well is connected with the German folk belief that little children are fetched by the stork from a pond. This pond is the Urd well, and the stork takes the place of the swan, which is rare among us, for the Edda says: “Two swans also feed at Urd’s well, and from them comes the swan race of that name.”

The first three humans of the new post-Sintbrand age appear in various mythologies. They are particularly clearly depicted in one of the American traditions, where the old foster father is named Botschika, his foster daughter Batschue, and the boy born shortly after the fire rain, the foster son, is called the “ancestral husband.”

In the tradition of the ancient Saxons, only the old foster father appears clearly under the name Wodan, while his two foster children, Donar and Sarnot, are less prominent. Also, in the trinity mentioned by Caesar—sun, moon, and fire—who, as he writes, were worshipped by the Germans, these three are again to be found: the sun represents the foster father, the moon the foster son, and the fire the foster daughter, as goddess or guardian of the hearth fire.

The symbolism of the first humans as sun, moon, and Venus also appears in America, although this symbolism or veneration of the ancestors in the heavenly bodies is not uniform everywhere. In some regions, the sun was considered the symbol of the foster father, the moon that of the foster son, and the star Venus that of the foster daughter. In other regions, the moon was assigned to the foster daughter and the star Venus to the foster son. Elsewhere, the sun represented the foster son and the moon the foster daughter; or vice versa, so that the sun symbolized the foster daughter as the elder of the two siblings and the moon the foster son as the younger or smaller one. In that case, the foster father was then symbolized by the rainbow or by the dawn, which precedes the sun. The latter, as well as the dawn, sometimes—apart from an occasional designation for the foster daughter—also served as a symbol for the mother of the two children who perished during the Sintbrand. Consequently, the most famous descendants of the ancestral couple were later symbolized by the descendants in stars or constellations, such as Jupiter, Mars, Mercury, Saturn, Hercules, the Pleiades, Hyades, etc. This star cult is thus nothing other than an ancestor cult. This forms the foundation of the various religions, which are composed of ancestor cult and moral law or moral service.

Biblical tradition also begins with three persons. Of these, God the Father is identical with the foster father, while Adam represents the foster son and Eve the foster daughter. The only difference is that Eve was the elder and Adam the younger, and that Eve was not taken from Adam’s side but rather that Adam had to be cut from the body of his mother, who succumbed to the injuries she suffered in the Sintbrand. As the Bible then correctly continues, the ancestral couple had three sons, while the daughters—whose number was four—are not further mentioned. Of these four daughters, the eldest remained unmarried, while the other three couples propagated the Aryan tribe.

During the first period after the Sintbrand, the ancestral couple and the first generations stayed at the Urd well; later, when the tribe had grown in numbers, they again resettled in the great plain, which was then once again cultivated.

Third Section

In the Bible, at the very beginning of the creation of man, the existence of irrigation is mentioned:

“And a river went out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it parted and became four main rivers.”

Thus, irrigation already existed there since the pre-Sintbrand times. Even if the old system might not have been put into use or needed by the ancestral couple and the first generations, it must have been restored and expanded later, as the tribe grew larger, so that food could again be provided throughout the year.

This tradition in the Bible also appears—only in more detail and precision—in Plato’s account. According to him, a main canal encircled the plain, collecting the rivers flowing down from the mountains. From this main canal, other interconnected canals branched off from its upper part, leading through the plain, so that it was crisscrossed by a proper network of canals and could be irrigated.

The construction of the canals probably began at the start of the second world age, after the first world age ended with a terrible drought that claimed the lives of many people, while the rest were decimated by the wild animals on Atlantis, which, driven by hunger, attacked the humans. Just as the Aryan spirit invented a remedy for every evil, so too did it likely invent irrigation and the spear to avoid such disasters. With the help of this irrigation, the extremely fertile plain, located in a warm climate, produced crops continuously. The irrigation system was therefore as valuable and nourishing for the inhabitants of the Atlantean plain, or Midgard as it is called in the Edda, as if milk had flowed through it. From this comparison arose the expression “the land flowing with milk and honey.” This is a tradition that the Bible later transferred to the land of Canaan.

What the main diet of the Aryans was cannot be clearly determined from the traditions. David says:

“Content with what nature freely gave,

Man fed on what the tree and shrub

Brought forth in fruit and food

And what the hedgerow and hawthorn gave him.

The oaks gave him his daily bread,

The thorny blackberry bush the juicy berries.”

Accordingly, it would seem that the Aryans lived on wild fruits that grew naturally. This may have been partly the case, but they would not have needed irrigation for that. Since such irrigation was present, they must have possessed cultivated plants and practiced agriculture many thousands of years before the Sintbrand.

As the oldest staple crops of Atlantis, only those that were found in both the Old and New Worlds and that may have been brought from Atlantis by migrating Aryans—along with the knowledge of irrigation—to both the warm regions of the Old World and to America before the Sintbrand, can be considered. These plants are: the banana, taro (a tuber crop), and the bean; these plants are also very responsive to irrigation. Additionally, the yam and the coconut palm come into consideration, for the latter was also native to Atlantis according to Plato.

Humboldt says that the banana plant has accompanied man since the earliest days of his civilization. Furthermore, if one considers that the banana has completely suppressed seed formation in favor of its fruit flesh, then the frequently made claim that the banana is one of the oldest cultivated plants of the world is justified; its cultivation must have begun in the earliest prehistoric times. In the Bible, this fruit is also mentioned, albeit under a different name: The scouts sent into the Promised Land brought, among other fruits, a bunch of grapes “and carried it between two men on a pole.” The land “flowing with milk and honey” did not refer to the land of Canaan but rather to the land of Atlantis, and the fruit that had to be carried by two men on a pole was not a grape bunch but a banana bunch, which can weigh up to fifty kilograms. The banana plant loves warmth and humidity and good soil. All of this existed in Atlantis, and whatever moisture was lacking was supplemented by irrigation; even today, the banana grows on the Azores. The designation of the banana as the “paradise fig” or “Adam’s apple” was probably not invented out of thin air but was likely contributed to by some ancient tradition.

According to Ovid, grain originally did not belong to man’s first foods, although it was cultivated during the Golden Age. Initially, it was probably cultivated by hand using a stick or a hoe-like tool, but already in the Silver Age, according to Ovid, cultivation was done with a plow and oxen. The Scythian legend also reports that the plow and the yoke were known in Atlantis, for among their first kings, as Herodotus reports, a plow, a yoke, an axe, and a cup—all made of gold—fell from the sky into the land of the Scythians. This means that these tools were already in use in Atlantis and that the Scythians brought some of them north with them when they migrated. In the Peruvian tradition, the precise time of the invention of the plow is also given: it was invented by Thor’s predecessor or father, who died in 1500 after the Sintbrand.

In various traditions, it is said that the primal mother knew weaving and taught it. In the Bible, however, it says that the first humans sewed fig leaves together and made themselves aprons. Presumably, besides weaving, there was also another method of making clothing, which must be considered the older one; but this did not consist of weaving fig leaves, rather of processing the bark of the fig tree into fabrics. This is done by removing the hard outer bark from the stripped bark, after which the remaining bast layer is beaten until it becomes a cloth-like material that serves as clothing. Even today in Africa—especially in regions where banana cultivation is common—such bark fabrics are still made, preferably using the bark of wild fig trees.

The consumption of meat among the Aryan population only emerged in post-Sintbrand times, when through immigrant non-Aryans and mixed races in the settlements on Atlantis itself a mixed population arose, which could not entirely abandon the customs of their non-Aryan ancestors. While the non-Aryan races consumed everything that could fill the stomach and satisfy hunger, the Aryans had until then lived only on plant-based food, which was also carefully selected for its digestibility. Later, when they tried meat, it turned out that it was not only less beneficial to health but that various ailments appeared depending on the type consumed, which made it advisable to limit meat consumption or even to prohibit certain kinds altogether. Consequently, regulations may have been issued that directly banned some types of meat and required fasting from meat at other times. The health benefits of fasting and abstinence in all respects for the human body had likely already been known and practiced in earlier times in Atlantis.

The dietary laws found among various peoples thus partly go back to these ancient Atlantean regulations, which probably underwent various changes over time. Some prohibitions also stem from the later totem system, for the totem animal or the totem plant, which a particular non-Aryan or mixed tribe bore as their emblem, could not be eaten by them. Partly, some prohibitions were also of political origin, in which one party or tribe declared the sacrificial animal of another party or tribe to be unclean to prevent the mixing of their own people with the supporters of the opposing party. That such prohibitions were possible is also taught by Germanic history: among the Germans, the horse was a sacrificial animal, whose consumption was later forbidden by the Christian priesthood.

During the world ages before the Sintbrand, the seat of government was presumably in the middle of the great plain; after the Sintbrand, this seat was moved to the area of the Yggdrasil and the Urd well, which in Norse tradition is called Idafeld. Here, at this sacred place, which was the starting point of the new race, not only the seat of the highest government was established but also the institutions for the boys and girls who were taught all skills here. Furthermore, living quarters were established here for the sick and the disabled, as well as for those who remained unmarried and who now engaged in weaving and in the production of other equipment for the administration and the institutions of Idafeld.

This Idafeld lay at the edge of the plain and was separated from it by one or more bodies of water or watercourses. These were later connected to establish a link with the canal system and to better defend Idafeld, so that Idafeld thus became an island. Furthermore, this water belt was connected to the sea by a long canal to allow direct access for seafaring vessels to the capital.

The water that separated Idafeld from the plain (apparently two rings of land and two rings of water were later created around Idafeld) was later bridged so that Idafeld could be reached on foot from the great plain. According to Plato, the bridge was one hundred feet wide and built from white, black, and red stones. This bridge is also mentioned in Norse tradition under the name Bifröst; it says of it: “It has three colors and is very strong and made with more skill and craft than other works.” In the memory of the Aryans who migrated north, the bridge Bifröst was as beautiful and colorful as the rainbow. Over time, as the real meaning of the traditions faded, the bridge, “as beautiful as the rainbow,” was then mistaken for the rainbow itself. Norse tradition also says: “That the gods made a bridge from heaven to earth, called Bifröst.” By “earth” is meant the great plain, while “heaven” means the hill or mountain behind the Urd well, which was called Himmelsberg, or simply “Himmel.” On top of the Himmelsberg, which was later terraced, stood the “Himmel’s castle” with a throne for the Allfather (king), from which he had a wide view in all directions. The Himmelsberg also contained large cavities inside, which either existed naturally or were artificially expanded; these were connected with each other and also with the cave at the Urd well, as well as with the temple or palace—the castle—at the top of the Himmelsberg by passageways. These cavities in the interior of the mountain served partly as treasure chambers and partly as burial places for princes and other notable figures who had earned merit for the tribe; their bodies were carefully embalmed and then laid to rest in the Himmelsberg. The other members of the tribe, on the other hand, were buried in stone graves. Later, when the tribe had grown large and diseases had been introduced through contact with overseas settlements, cremation of the dead on wooden pyres began.

This should not be confused with the later custom of burning bodies in a volcano. Even the living who did not show obedience to the priest-king and his laws in late Atlantean times or who had made themselves otherwise unpopular were punished by being thrown into the eternal fire that burned in the volcano’s interior, the hell region. Likewise, this punishment was carried out on the corpses of those who had sinned against the laws of the priest-king or who were otherwise in opposition to the priestly rule. For example, the corpse of Baldr was secretly stolen by his enemies and thrown into a volcano. By contrast, personalities who had proven themselves to be loyal supporters of the priest-king or had otherwise earned his favor were given an honorable burial, if not on Idafeld, then at least on the island.

Even before the priesthood came into power, when the government on Atlantis still lay in the hands of the kings, it seems to have been customary for deceased esteemed Aryans from overseas settlements to enjoy the privilege of being buried in their homeland on the island. This must also have been the case here in the north, as the expression “to set sail,” which is often colloquially used for “to die,” indicates. Later, when the rule on the island and in most overseas territories fell to the priest-king (though the Aryans who had migrated north to Europe were never under his rule), this practice was probably expanded to gain even more influence. The decision as to whether the corpses of the deceased were to be buried on the island or handed over to the eternally burning fire in the volcanoes was then transferred to a special death tribunal on the island of Atlantis.

The great plain, originally the only inhabited area, which occupied the south of the island of Atlantis, was divided into nine districts, and the Aryan population of each district was again divided into two groups. This resulted in eighteen groups or clans, each of which bore a special name formed from the consonant of the respective landscape and a vowel (a syllable). The difference was that in one group the consonant of the landscape came first and the vowel followed, and in the second group of the same landscape, the vowel came first and the consonant followed. From the eighteen groups or original clans into which the population was originally divided, new clans later emerged through intermarriage, carrying new names formed from the old ones, with the name of the paternal clan placed first and that of the maternal clan second.

The migrating clan members then took these names with them to their new settlements in various parts of the world, where they often survived as names of regions, tribes, mountains, rivers, and places. It was customary for the clans to name the places, areas, or rivers where they settled after their own clan names. The same was true here in the north, which became the second homeland for the Aryan people. Here, the individual clans can even still be traced in the family names, as these are partly nothing other than old clan names, and their bearers are still members of these clans.

The division of the inhabitants of each district into two groups or clans, as well as the naming of the sub-clans that arose from the intermarriages with special clan names, was done for the sake of work organization, as the two groups of each district took turns working each week. According to the oldest Atlantean calendar, the year was divided into eighteen months corresponding to the nine landscapes with two population groups each. Each month was divided into four weeks of five days each. These eighteen months of twenty days each totaled 360 days; the remaining five days were inserted as intercalary days. To bring the civil year of 365 days in line with the solar year, 13 days were inserted at the end of a 52-year cycle, and at the end of ten 104-year cycles, seven days were dropped. Between the Sintbrand and the Sintflut, several changes were made to the calendar system. It is likely that the later division of the year into twelve months and the week into seven days also originated in Atlantis, since this division also existed in America.

Apparently, this year and week division was also brought to Germany by migrating Aryans, as even before the introduction of Christianity, there was a weekly holiday in the north, and this was Monday. This also relates to the term “Blue Monday,” because blue, besides being the body color of the princes, had also become a sacred color. The other sacred color was white.

At the head of each district stood an elder or prince, who was elected by the district inhabitants and held his position for one year or several years. These nine princes or the entire tribe then elected another prince as their head or king (Allfather), who also had authority over Idafeld. Over time, as the administration became more complex, the office was filled for life, and later the position—especially that of the king—became hereditary, passing from father to one of his sons. These ten Atlantean princes were then joined by a council or parliament consisting of fifty representatives of the people. Later, the leader of the army (Mars, Ares) and the leader of the fleet (Neptune, Poseidon, Midgard serpent) were added to these ten princes, and they also oversaw the connections with the settlements. This brought the number to twelve. Over time, as the institutions of Idafeld became ever more extensive, a separation occurred when it received its own head, which in Norse tradition (the Edda) bears the title Loki, and through this the number thirteen became an unlucky number.

Another prince who was on the island but did not belong to the old council of Aryan princes was the head of the non-Aryan and mixed population settled in the volcanic mountains. He is named in the various traditions as Vulcanus, Hades, Hephaestus, Pluto, or, as in the Edda, Fenriswolf; other names for him are Devil, Satan (although sometimes this also refers to Loki), as well as fire god and prince of hell, as lord of the volcano or hell region.

Although Idafeld produced some harvests from its own facilities, these were by no means sufficient to feed the population of the many institutions that were established on Idafeld over time. Since all these institutions and administrative facilities served public purposes, they had to be supplied by the people, that is, the population of the nine districts. For this purpose, the nine regions had to deliver a portion of their harvest to Idafeld, which lay at the edge of the plain and thus formed a tenth region. From this comes the term “tithe,” which originally did not mean the surrender of one-tenth of the harvest but rather the supply of food to the tenth region, Idafeld.

The palaces and temples built on Idafeld, as is evident from various traditions, were covered and overlaid with gold and silver and sparkled inside with these precious metals, which were abundant in Atlantis. For other buildings, they used stones of the same color, but also stones of different colors. The ring walls also received a coating of tin or bronze. The buildings of Idafeld must have made an overwhelming impression in later times, when everything was completed and beautifully decorated, an impression that one can hardly imagine today and which, especially in terms of the use of precious metals, has never been equaled anywhere on earth.

Fourth Section

A very detailed and vivid tradition about Atlantis was preserved among the Egyptian priesthood, who shared it with the Greek scholar Solon during his visit to Egypt. From his descendants, Plato passed it on to posterity as follows:

“I will now tell this ancient story that I heard from an old man. Kritias was, according to his own account, almost ninety years old at the time, and I was about ten; it was on the festival day of the Apaturia, and it was celebrated in the usual manner, with the fathers offering prizes to us boys for the best recitation of poetry. Many of us recited, among other poems, verses by Solon, which were still quite new at that time. One of our group—whether he truly thought so, or simply wanted to say something kind to Kritias—remarked that Solon seemed to him to possess the greatest wisdom and also the highest nobility among all poets. The old man—I can still see him before me—was very pleased and replied, smiling: ‘Yes, my dear Amynandros, certainly he would have become as famous as Homer, Hesiod, or any other poet, if only he had not practiced poetry as a sideline, but had devoted his full effort to it as others did! And if only he had completed the story he brought back from Egypt! But he had to leave it unfinished because of the internal unrest and all the other troubles he found upon his return.’

‘What was that story?’ the other asked. ‘The story of the greatest and most famous deed among all those our city ever accomplished; but because of the long time that has passed and the deaths of its heroes, the story has not come down to us.’ ‘Tell me from the beginning,’ the other replied, ‘what and how and from whom Solon heard and reported it.’ Kritias began: ‘In Egypt, in the Delta, where the Nile splits at its mouth, there is a district called Sais, and the largest city of that district is also called Sais, the birthplace of King Amasis. The inhabitants of this city consider a goddess as their founder, whom they call Neith in Egyptian and, as they claim, Athena in Greek; hence they were great friends of the Athenians and in a way akin to them. Therefore, when Solon visited them, he was treated with great honor, and when he inquired of the priests—who were especially knowledgeable in these matters—about the earliest times, he found that none in Hellas even had an inkling of these things.

Once he wanted to get them to tell him about the ancient times and began to relate to them the oldest stories from Hellas—about Phoroneus, said to be the first man, about Niobe, and about how after the flood only Deucalion and Pyrrha survived; he listed the genealogy of their descendants and tried, by calculating the years assigned to each of those he mentioned, to determine the times. Then one of the priests, a very old man, said: ‘Solon, Solon, you Hellenes are always children, and there is no such thing as an old Hellene!’ ‘What do you mean by that?’ asked Solon. ‘You are all young in soul,’ the priest replied, ‘for in your minds there is no ancient tradition and no knowledge hoary with age. The reason is this: many and various have been the destructions of mankind and will be again, the most frequent through fire and water, but also through countless other causes.

For example, what is told among you about Phaethon, the son of Helios, how he once harnessed his father’s chariot and, unable to control it, burned everything on earth and was himself struck by lightning and killed—that sounds like a fable, but the truth behind it is a deviation of the heavenly bodies that revolve around the earth, causing at long intervals a great fire that destroys everything on earth. In such a catastrophe, the inhabitants of the mountains and high, dry regions perish more than those living by rivers and the sea; but we are always saved by the Nile, our benefactor in every trouble—even in this case. When the gods flood the earth to cleanse it, only the herdsmen and shepherds of the hills survive, while those living in the cities near your rivers are swept into the sea. Here in our land, the water does not pour down from the sky to flood the plain; rather, everything rises from below. For this reason, everything here is preserved and considered the oldest. In fact, wherever the climate is not too extreme in cold or heat, humanity always exists, sometimes in greater, sometimes in smaller numbers. Whatever has happened anywhere in the world that is noble or great or otherwise notable is written down in our temples from the earliest times and thus preserved. But with you and with other nations, every time the usual cycle ends with a flood from heaven, only the illiterate and uneducated survive; and so you become like new-born children all over again, knowing nothing of what happened in ancient times—either here or among yourselves.

Your genealogies, dear Solon, as you just recited them, are little more than children’s tales. You know of only one flood, whereas many have taken place; and you do not know that the most excellent and noblest race of men once lived in your land—from whom both you and your whole city are descended—though only a small remnant of them survived. All this has been lost to you because for many generations your ancestors died without leaving any written record. Before the great destruction by water, the state that is now called Athens was the bravest in war and had the best constitution in every way; it performed the most glorious deeds and had the best laws of any under the sun. Solon marveled greatly at this and eagerly begged the priests to tell him in detail the whole story of his country’s early history in correct order. The priest said: ‘Nothing will be withheld from you, Solon, and I will tell you all, for your sake and for your city’s sake, but above all for the sake of the goddess who founded and raised both your state and ours, nurturing yours a thousand years earlier with the seed she took from Gaia and Hephaestus, and later ours in the same way. According to our sacred writings, the constitution of our state has existed for eight thousand years. Your fellow citizens therefore lived nine thousand years ago, and I will now briefly describe to you their constitution and the greatest of their deeds. We shall talk about all this in detail another time, with the aid of the sacred writings.

Of their constitution you may form an idea by comparing it to ours here, for many features of your ancient order can still be seen in our present arrangements: a separate priestly class, then a class of artisans, each working separately and not mixing with the others, and the shepherds, hunters, and farmers. And finally, you will have noticed that here too the warrior class is separate from all the others, with its only duty being to care for military affairs by law. Their weapons were the spear and the shield, which we adopted from the peoples of Asia, just as the goddess first taught them to you. You also see how much care our lawgiver has given from the very beginning to the cultivation of the mind—selecting from all the arts dealing with the universe, including prophecy and medicine and the divine arts, everything that is useful to human life, and appropriating these arts and all that pertains to them. Following this entire arrangement, the goddess first founded your state, choosing the place of your birth with a view to the happy blend of the seasons there, which would best produce wise men; since the goddess loved both war and wisdom, she chose the place that would produce men most like herself and first settled them there. Thus you lived there under such a constitution and many other good arrangements, surpassing all other men in every virtue, as might be expected of descendants of gods.

Among all the great deeds of your state that we read about with admiration in our records, one stands out for its greatness and heroism: our writings tell of a mighty power which your state defeated when it arrogantly marched against all of Europe and Asia from the Atlantic Ocean. For at that time one could still sail that ocean; for in front of the mouth that you Greeks call the ‘Pillars of Heracles’ lay an island larger than Asia and Libya combined. From it one could then cross to other islands, and from those islands to the entire opposite continent that encloses that truly boundless ocean. Everything within the said strait seems like a harbor with a narrow entrance, but that sea is truly an ocean, and the land around it rightly deserves to be called a continent. On this island of Atlantis, a great and wondrous royal power arose, ruling not only the whole island but also many other islands and parts of the mainland; in addition, their influence extended over Libya as far as Egypt and over Europe as far as Tyrrhenia. This power once tried to subjugate with one blow all lands within the strait, including ours and yours. Then, Solon, the strength of your city shone forth in all its brilliance and heroism: surpassing all others in valor and military skill, it led the Greeks, and when the others fell away, relying on its own strength, it overcame the invaders, erected trophies, and thus saved those who had not yet been enslaved—becoming a glorious liberator of us all within the Pillars of Heracles.

Later there were violent earthquakes and floods, and in a single dreadful day and night all your warriors sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis likewise disappeared into the sea. Therefore, the sea there is now impassable and unsearchable, because of the great mass of mud that the island produced when it sank.”

First of all, let us recall that a full nine thousand years have passed since, as the story goes, that war took place between those living beyond the Pillars of Heracles and those within them, which I will now describe in detail. Over the one side, our state ruled and carried the war to its conclusion; over the other side, the kings of Atlantis. This island was, as noted, once larger than Asia and Libya combined, but it sank due to earthquakes and left behind an impassable, muddy shoal that prevents any passage to the open sea beyond.

Now, in the nine thousand years that have elapsed since that time until now, many great floods have occurred. As a result, the soil that was washed down from the heights during these times and events did not, as in other regions, accumulate in layers, but was carried away all around and disappeared into the depths. Thus now, as happens with small islands, compared to the land of that time, only the bones of the sickly body remain, as the fertile and loose soil was washed away and only the barren skeleton of the land is left. In those ancient times, when the land was still intact, its mountains were not high and covered with soil, and its plains, which are now called stony ground, were filled with rich soil; on the mountains stood dense forests, of which even today clear traces still exist. For now, some mountains only provide enough food for bees, yet it is not so long ago that beams made from the trees there were still well preserved—beams that were used for the largest buildings. The land also bore many tall fruit trees and provided herds with inexhaustibly rich pasture; especially, too, the rainfall throughout the year brought it abundant prosperity, for the water did not, as it does now—where, due to the barren soil, it flows into the sea—go to waste, but the rich soil absorbed the rain and stored it in its clayey subsoil and then let it trickle down from the heights into the valleys, thus providing abundant springs and rivers everywhere; even today, sacred signs can still be found at their ancient sources, proving the truth of what is still told about them.

Such was that once so fertile land, cultivated by true farmers who truly deserved that name, who dedicated themselves entirely to agriculture, pursued the right, and were gifted, as they also enjoyed the best soil, the most abundant irrigation, and, as far as the climate is concerned, the most suitable alternation of the seasons.

But now let us also describe the conditions that prevailed among their adversaries and developed among them from the beginning; I hope that my memory will not fail me regarding what I already heard as a boy, so that I can tell you, my friends, everything in detail. I must first preface my account with one small detail so that you are not surprised if non-Hellenic men bear Hellenic names; you should know the reason for this. When Solon wanted to use this story for his poetry, he made careful investigations into the meaning of the proper names and found that those ancient Egyptians who first inscribed them had translated them into their own language; therefore, he himself also translated the meaning of each proper name and wrote it down as it sounded in our language. These notes were also with my grandfather and are still with me today, and I examined them thoroughly as a boy. Therefore, do not be surprised if you hear proper names there as here; you now know the reason. But now to our long story, whose beginning sounded approximately as follows.

We have already reported above that the gods divided the whole earth among themselves into larger and smaller portions and founded their sanctuaries and places of sacrifice: thus Poseidon was assigned the island of Atlantis, and he settled his descendants, whom he had fathered with a mortal woman, on a place on the island of the following nature.

On the coast of the sea, in the middle of the whole island, there lay a plain that was said to be the most beautiful and fertile of all; at the edge of this plain, about 30,000 feet from the sea, was a low hill. On it lived Evenor, one of the original men who had sprung from the earth, with his wife Leukippe; they had an only daughter, Cleito. When the girl had grown up, her mother and father died, and Poseidon fell in love with her and united with her; he surrounded the hill on which she lived with a strong enclosure: he made several rings of land and water around the hill, two of land and three of water, each equally distant from the others in all directions, so that the hill became inaccessible to people, as at that time there were no ships and no navigation.

He, as a god, furnished this hill, which had thus become an island, in the best way possible: he caused two springs to rise from the earth, one warm, the other cold, and made the land yield abundant fruits of every kind. He begat on her five pairs of twin sons, had them raised, and then divided the entire island of Atlantis into ten parts and assigned to the firstborn of the eldest pair the dwelling of his mother and the surrounding land as the largest and best portion, and appointed him king over the others; but he made them also rulers, each over many people and a large territory. He also gave all of them names, and he called the eldest, the first king who ruled at that time, Atlas, from whom the whole island and the ocean received their name; his twin brother, who received the outermost part of the island, from the Pillars of Heracles to the region of present-day Gadeira, was given in the local language the name Gadeiros, in Greek Eumelus—a name that was to lead to that name of the land. From the second pair, he named one Ampheres, the other Evaemon; from the third, the firstborn Mneseas, the younger Autochthon; from the fourth, the elder Elasippos, the younger Mestor; and from the fifth, finally, the elder received the name Azaes, the younger Diaprepes. All these and their descendants lived for many generations on the island of Atlantis and ruled also over many other islands of the Atlantic Ocean; they even extended their rule as far as Egypt and Tyrrhenia.

From Atlas sprang a numerous lineage, which was not only highly respected in general but also maintained the kingship for many generations, as the eldest always transferred it to his firstborn son, whereby this lineage preserved such a wealth of prosperity as had never existed before in any kingdom and would hardly exist again in the future; they were also provided with everything needed in a city and in the countryside. Although foreign countries supplied many things to these rulers, most of what they needed for life was provided by the island itself. First of all, everything that mining offered in the way of pure or smeltable metals; among them especially a kind of orichalcum, now known only by name, but at that time valued more highly than anything except gold, which they mined in many places on the island.

The island also produced in rich abundance everything that the forest offers for the works of builders and nourished wild and tame animals in great numbers. There were also many elephants; for not only did all kinds of feed grow for all kinds of animals in the marshes, reeds, and rivers, on the mountains and in the plains, but also in equal measure for this, the largest and most voracious of animal species. Furthermore, all the fragrant substances that the earth now produces in roots, herbs, woods, exuding juices, flowers, or fruits were also produced and cultivated in abundance on the island; likewise, the “sweet fruit” and the fruit of the field, which serves us for food, and everything else that we otherwise use as vegetables under the general name of greens; also a tree-like plant that yields drink, food, and oil all at once; and finally the quickly perishable fruit of the fruit tree, intended for our delight and pleasure, and all that we serve as dessert to stimulate the appetite of the already sated stomach; all this the island produced then in wonderful beauty and in inexhaustible abundance, still accessible to the rays of the sun.

Since the land offered them all these things, the inhabitants built temples, royal palaces, harbors, and shipyards, but they also organized the entire country and proceeded according to the following arrangement. First, they built bridges over the canals that surrounded their old royal residence and thus established a connection with the royal castle. This royal castle they built from the beginning on the very residence of the god and their ancestors; each inherited it from the other, and each sought to embellish it as best he could and surpass his predecessor in it, until finally their residence, because of its size and beauty, offered a wondrous sight.

First they dug a canal from the sea to the outermost ring, three hundred feet wide, one hundred feet deep, and thirty thousand feet long, enabling ships to sail into it from the sea as into a harbor, and made it wide enough to accommodate even the largest ships. They also cut through the earth walls between the ring-shaped canals beneath the bridges and thus created a passage wide enough for a single trireme between the different canals; they then bridged this cut again so that one could sail underneath with ships, for the edges of the earth walls were high enough to rise above the sea. The widest of the ring-shaped canals was eighteen hundred feet wide; the following earth belt had the same width; the next ring-shaped canal was twelve hundred feet wide, and the adjoining earth belt was the same; finally, the innermost canal that surrounded the island itself was six hundred feet wide, and the island on which the royal castle stood was three thousand feet in diameter.

They surrounded this island, the earth belts, and the one-hundred-foot-wide bridge all around with a stone wall and built towers and gates on the bridges facing the entrance from the sea; the stones for this, white, black, and red, were quarried from the slopes of the central island and from the inner and outer sides of the earth walls; in this way they also created hollows on both sides of the earth walls for shipyards, which were covered over by the rock itself. For their buildings, they used some stones of the same color and also combined differently colored stones for visual enjoyment, thus giving them their full natural charm.

They covered the outermost earthwork wall with a coating of bronze, the innermost wall they covered with tin, and the citadel itself with orichalcum that shone like fire.

The royal seat within the citadel was arranged as follows: In the middle stood a temple dedicated to Cleito and Poseidon; it could only be entered by priests and was surrounded by a golden wall. It was in this temple that the race of the ten princes had been conceived and born. Every year, from all ten districts, the first fruits were sent there as offerings for each one of them. Also there stood a temple of Poseidon, six hundred feet long, three hundred feet wide, and of corresponding height, built in a somewhat foreign architectural style. The entire outer surface of the temple was covered with silver, and the inner parts with gold. Inside, the ceiling was of ivory adorned with gold and orichalcum, and the walls, pillars, and floors were clad with orichalcum. Golden statues were placed inside, showing the god himself, standing in his chariot and driving six winged horses, so large that his head touched the ceiling, surrounded by a hundred Nereids on dolphins—because it was then believed there were that many. Besides, there were many other statues in the temple, dedicated by private citizens. Outside, there were golden statues of the ten kings themselves, their wives, and all their descendants, as well as many other offerings from the kings and from private individuals of the city itself and the overseas territories they ruled. The altar matched this splendor in its size and construction, and the royal palace was also in accordance with the size of the realm and the grandeur of the sanctuaries.

They also made use of the two springs—one warm, one cold—which flowed abundantly and provided delicious and wonderfully useful water for every need; they built buildings around them with appropriate trees planted and constructed bathing facilities, partly in the open air and partly in covered rooms with warm baths for winter use, separate for royalty and commoners, as well as special baths for women and swimming pools for horses and other draft animals, all of which were suitably appointed. The wastewater was partly directed into Poseidon’s grove, where trees of every kind grew tall and beautiful thanks to the richness of the soil, and partly it was channeled over bridges into the outer ring canals. There were sanctuaries of many gods there, many gardens and training grounds—some for men and some for chariot teams—on the islands formed by the earthworks, and in the middle of the larger island was a special racecourse six hundred feet wide, laid out around its entire circumference for chariot races. Around this racecourse were the residences of most members of the royal guard. The most trusted of them were stationed on the smaller earthwork closer to the citadel as sentries, while those who had shown particular loyalty lived in the citadel itself near the palace.

The shipyards were full of triremes and all the equipment needed to outfit such ships, which was kept in good condition. Such was the arrangement of the royal residence. When one passed beyond the three harbors outside it, one came to a wall that began at the sea and ran in a circle, enclosing the largest ring and the port, at a distance of thirty thousand feet on all sides; it ended at the same spot at the mouth of the canal into the sea. This entire area was filled with densely packed houses; the harbor and the largest port bustled with ships and merchants from every region, and there was constant noise, clamor, and shouting of all kinds day and night.

This concludes pretty much everything that was once told to me about the city and that former residence of the kings. Now I must also try to report on the natural features and administration of the rest of the land.

First, it is said that the entire island rose very high and steeply out of the sea, except for the area near the city, which was a flat plain entirely surrounded by mountains that ran down to the sea. It was level and even, longer than it was wide, extending three thousand stadia in length on one side and two thousand stadia in width from the sea inward at its center. This part of the entire island lay on the south side, protected on the north by the northern wind. The surrounding mountains were said to have surpassed all present-day ones in number, size, and beauty; they contained many densely populated villages, rivers, lakes, and meadows with ample pasture for all kinds of tame and wild animals, and finally great forests that, in their varied array of trees, supplied timber for every kind of work. Such was the natural condition of the plain, which many kings had worked to develop further. It mostly formed a complete rectangle; the missing parts were corrected by a canal drawn all around; what is reported about its depth, width, and length sounds almost incredible for a human-made structure, besides all the other works. This ditch was one hundred feet deep, six hundred feet wide everywhere, and ten thousand stadia in total length. It collected the rivers flowing down from the mountains, touched the city on both sides, and emptied into the sea. From its upper part, approximately one hundred feet wide canals were drawn in straight lines into the plain, each of which again emptied into the canal leading to the sea and were spaced one hundred stadia apart; by this means, timber was brought from the mountains to the city, as well as all other products of the land, using canals that crossed the main channels lengthwise and connected the city with them.

The land produced two harvests annually: one in winter thanks to the fertilizing rain, and one in summer thanks to irrigation from the canals. As for the number of inhabitants, it was determined that each property in the plain must provide a war leader; each property had a size of one hundred square stadia, and the total number of properties was sixty thousand. In the mountains and other regions, the population was said to be countless; nevertheless, all were assigned to one of these properties and its leader according to their respective villages. Each leader had to supply a war chariot, so that in total there were ten thousand such chariots for war; furthermore, each leader had to provide two horses and riders, a light chariot without a seat carrying a warrior with a small shield and the charioteer, plus two heavily armed soldiers, two archers, two slingers, three stone- and javelin-throwers, and finally four sailors for manning twelve hundred ships. That was the organization of the military in the royal state; in the other nine states there were different regulations, the discussion of which would take us too far afield.

The relationships of government and the state authorities were originally arranged as follows. Each of the ten kings governed the people in his own district from his city and was above most laws, so that he could punish and execute whomever he wished. The rule over themselves and their mutual relations was determined by the command of Poseidon, as passed down by law from their ancestors, engraved on a pillar of orichalcum in the middle of the island, in the temple of Poseidon. There they met alternately every fifth and sixth year, to give equal honor to the odd and even numbers, and there they deliberated on common affairs, investigated whether any of them had broken a law, and passed judgment on it. When they were about to pronounce judgment, they first exchanged a pledge of loyalty.

They held a hunt among the bulls that roamed freely in the sanctuary of Poseidon, using no weapons but only clubs and ropes, and prayed to the god that they might capture the animal he wished to be sacrificed. They then brought the captured bull to the pillar and sacrificed it on top of it, directly above the inscription. On this pillar was, besides the laws, an oath invoking severe curses on any who disobeyed. When they had sacrificed all the limbs of the bull to the god according to their customs, they filled a mixing bowl and poured a drop of blood into it for each of them, while the rest of the blood they threw into the fire and purified the pillar all around. Then they drew with golden cups from the mixing bowl, poured their libations into the fire, and swore, while doing so, to judge according to the laws inscribed on the pillar, to punish any who had committed an offense, and never to break any of those ordinances intentionally, and to rule and obey no one except the one who governed according to the laws of their ancestors. When each of them had pledged this for himself and his family, he drank and dedicated the cup as a memorial to the temple of the god; then he prepared his meal and took care of the needs of his body. When darkness fell and the sacrificial fire had gone out, they all donned a beautiful dark blue robe, lay down by the embers of the oath sacrifice, then extinguished all the fires in the sanctuary and received and rendered judgment at night whenever one accused another of breaking the law. At daybreak they inscribed the judgments on a golden tablet and dedicated this, along with the robes, as a memorial.

There were also many other laws concerning the rights of the kings, but the most important one was that none should ever take up arms against another, but that all should come to the aid of any who might try to overthrow the royal line in any city; after joint deliberation, as their ancestors had done, they were to decide on war and all other matters, but give the primacy and command to the lineage of Atlas. The right of a single king to put to death any of his relatives was only to be allowed if the majority of the ten approved.

This power, which at that time existed in those lands in such a manner and to such an extent, was led by the god against our land, according to the legend, for the following reasons: For many generations, as long as the divine nature was still active within them, they obeyed the laws and were kind and friendly to the divine, to whom they were related; their disposition was sincere and entirely magnanimous; in all the vicissitudes of fate and in their dealings with one another, they showed gentleness and wisdom. They considered all goods outside of virtue to be worthless and regarded their abundance of gold and other possessions indifferently, more as a burden. Their wealth did not intoxicate them, nor did it deprive them of their self-control or bring them down; rather, with sober insight, they recognized that all these goods could only flourish through mutual love combined with virtue, but would perish through eager striving for them, and with them, virtue itself would also vanish. With such principles and the continued activity of the divine nature within them, everything I described earlier flourished in the best possible way.

But when the divine part of their nature began to fade due to repeated and frequent mixing with the mortal, and the human nature became dominant, they could no longer endure their fortune, but degenerated. Anyone who was able to perceive this could see how shamefully they had changed, destroying the most beautiful thing of all their possessions; but anyone who could not see what kind of life truly leads to happiness thought them at that very time to be particularly noble and blessed, because they possessed unjust wealth and unjustly acquired power. But Zeus, the god of gods who rules according to eternal laws and was well able to see this, decided, seeing such a noble race sink so low, to punish them so that, brought to their senses, they might return to their former ways of life. Therefore, he gathered all the gods together in their most venerable dwelling place, which lies in the center of the universe and grants a view over everything that has a part in creation, and spoke . . .

Here the story breaks off. Because Plato only began to write it down in his later years, death probably surprised him before he could complete his work. However, from the account given at the beginning, we can piece together the conclusion: When all exhortations were in vain—that is, when the earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, which had already begun long before the final downfall of the island, did not bring about any improvement in the conduct of the mixed people of Atlantis—then, during a dreadful day and a fateful night, the island of Atlantis sank.

It is now suspected that Plato invented this whole story merely to present to his fellow countrymen an ideal state as it should be, and how it could collapse due to mismanagement. It is unlikely that Plato wrote down this story for purely didactic purposes, for then he would not have used the name of his ancestor to claim that Egyptian priests had told these events to Solon. Plato himself had also been to Egypt, and if he had wanted to present his fellow countrymen with a mirror image of a once-perfect state of his own imagination that had then perished due to its own faults, he could just as well have said he himself had heard it from the Egyptian priests. Precisely because he brings in the name of his ancestor, it must be seen as proof of the truth of Plato’s account; for it is not to be supposed that he would have misused the name of one of his ancestors. Solon had visited Egypt and there engaged in discussions with the most learned of the Egyptian priests on philosophical and historical matters. Given the respect he had as a Greek scholar, it is quite possible that the Egyptian priests let down their guard and shared things from their secret store of knowledge, which they otherwise guarded from their own people, with a foreigner they regarded as their equal in wisdom. Vanity may also have played a role, allowing them to present themselves as the more knowledgeable to this famous Greek scholar.

According to Plato’s account, the story of Atlantis also begins with four people: there is Evenor, who is identical to the foster father; Leukippe corresponds to Semele, whose daughter Cleito is the foster daughter; and Poseidon is the boy born in the cave by the lake, who in Greek mythology also appears as a river god. The Poseidon of Plato’s account, the ruler of the seas—i.e., the commander of the Atlantean fleet—has nothing to do with the sea god Poseidon. The note that when Cleito grew up, her father and mother died, is not entirely correct, for the mother died shortly after the end of the fire rain, while the foster father lived much longer and not only raised his foster son but probably also instructed his children in pre-deluge knowledge.

The foster father, as already mentioned, was a brother of Leukippe. Even if he was the oldest of Leukippe’s possible siblings, he would hardly have reached the start of old age at the time of the fire rain. Given the very moderate lifestyle of the Aryans in early Atlantean times, it can be assumed that he was granted a very long lifespan.

Such discrepancies, which are inevitable in oral transmission, continue to occur but can easily be corrected through comparison with other mythologies.

Fifth Section

In the tradition that survived in Peru about the ancient times of Atlantis, it is said: “These descendants (of the first human couple) lived in peace and unity with one another for about half a millennium.” Such peace would have reigned on Atlantis for many millennia prior as well, since the disturbance of this peace and unity did not arise internally but was instead brought to the island from the outside—by the three Thursen daughters, as they are called in the Edda.

Even before the Fire Rain, the Atlanteans had begun to cross the ocean surrounding the island, the Atlantic Ocean, to provide the Aryan offspring—who no longer had enough space on the island’s plain—with suitable land for settlements, since the volcanic and forested regions to the north of it were too difficult to cultivate. From the traditions of the Muzos in present-day Colombia (South America) and the Arcadians in the Peloponnese (Greece), it is evident that these peoples descended from Aryans who had migrated there before the Fire Rain. It is very likely that, at that time, Aryans had also settled in other parts of Europe, America, or Africa in particularly favorable locations that were easy to cultivate; however, they were either exterminated in wars with the native inhabitants of the new lands or intermarried with them. Over time, through increasingly extensive mixing, these descendants themselves would have reverted to a savage state, forgetting all traditions of earlier times.

Nevertheless, through these emigrants, many Aryan skills—such as the making of fire and the manufacture of stone tools—would have been brought to these new areas. Therefore, if traces of fire and old stone tools are found in very ancient layers, they are likely to come from Aryan emigrants who settled in those regions in pre-Fire-Rain times; from there, these skills could have spread further over time.

As the Aryan race on Atlantis grew so rapidly over the next centuries after the Fire Rain that overpopulation threatened, they would have recalled the traditions of the pre-Fire-Rain era, which their ancestors had received from the foster father, and again turned their steps overseas. The tribes—that is, human tribes, not tree trunks—that the Aryans encountered there, and which are called Ask and Embla in the Edda, lived in a completely primitive state. These tribes had to be taught by the Aryans who came to them—whether as emissaries or settlers—the knowledge of fire-making, agriculture, various crafts, as well as the basic concepts of morals and law and the division of time; in short, these Aryans had to first make these tribes human.

The reports about the primitive races of Mesopotamia, East Asia, Africa, Australia, and America all consistently state that these races also lived in a completely savage state and that they had not created even the beginnings of culture on their own but that everything was first brought to them by the Aryans. Some of these races have proven to be very apt students in certain respects—though this may also have been due in part to the Aryan blood they received through mixing with the Aryans.

*) Anyone who is further interested in these questions, as well as in the many others that cannot be treated in more detail here, will find more information in the main work Origin and History of the Aryan Race.

Sixth Section

Whether the tribes of Ask and Embla were in the Old or the New World (though the former is more likely) and in which century the Aryans from Atlantis made contact with them is not further specified. It is quite possible that this happened before the end of the fifth post-Fire-Rain century.

The three Thursen daughters who came to Atlantis after the expiration of the first five hundred years were apparently no ordinary Thursen daughters, but, judging by the expression "rich in power" in the Edda, the daughters of leaders of the tribes or peoples whom the emigrating Aryans had encountered. Furthermore, it seems that these three Thursen maidens were married to some of the princes of Atlantis, either for political reasons or to accommodate the tribes of Ask and Embla.

As also emerges from the Peruvian tradition, the three Thursen maidens did not come alone but brought followers with them, and it is assumed that part of this entourage remained with the three Thursen daughters in beautiful Atlantis. In the Edda, a Heid is then soon mentioned who appears to be somehow connected with the Thursen daughters, either because she was one of them or, more likely, a descendant or relative of them or of their Thursen kin or followers who remained on Atlantis. This Heid possessed the art of brewing—that is, the art of making intoxicating beverages.

According to the American tradition as well, the invention of an intoxicating drink by a woman marked the beginning of the time of misfortune in the history of Tula, i.e. Atlantis. In the Bible, it is Eve who, by consuming a forbidden fruit, commits such a sin that she and her husband are expelled from Paradise. Eating a harmless fruit could not have caused such ruin; rather, the brewing art, through the production of intoxicating beverages, has indeed caused unspeakable harm. It was probably a fruit—perhaps even grapes—that was pressed experimentally rather than eaten fresh. Such a test would easily explain the invention of an intoxicating drink, for pressed juice soon ferments and becomes intoxicating.

The expulsion from Idafeld was probably not even a punishment for making intoxicating drinks at first, but only the subsequent excesses made it necessary. In the American tradition, a festival is mentioned that was celebrated on the "Schaumberg" with the pulque invented by the woman Maiavel, and during which Prince Cuerteco became so intoxicated that he exposed his shame. The Schaumberg here refers to the "Himmelsberg," the hill or mountain behind the Schaumbrunnen, the Urd-Brunnen.

This event is also reported in the Bible, but in a different version. There it is Noah, of whom it is said: "And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent." This unique incident then caused the Aryans to put an end to all this activity by expelling them from Idafeld.

Instead of completely removing the expelled ones—who were probably mostly of Thursen descent—from the island (which may no longer have been possible due to their numbers), they were assigned the uninhabited mountainous part of the island. Until their expulsion, they were probably also supplied with provisions from the plains whenever the orchards of Idafeld did not produce enough. That now ceased, and they had to work the soil in the mountains by the sweat of their brow and procure their own food or forage in the forests.

According to the Bible, Idafeld then had to be guarded against the return of the expelled. Especially the Tree of Life, the Yggdrasil, was protected. From the entire third chapter of Genesis, it is clear that the strangers had access to the fruit trees present on Idafeld, including the oaks in the sacred grove. Only the Yggdrasil was excluded because its fruits were collected and enjoyed annually at the memorial festival of the Aryan tribe. Thus Yggdrasil was the tree whose fruits were not to be touched or eaten. But even this prohibition was not respected by the strangers.

Thus, the event of the Fall did not occur during the lifetime of the first human couple but at least five hundred years later. Moreover, the woman who instigated the Fall was not the original mother Eve, but another Eve and also not an Aryan. This example shows how traditions were transferred in the myths and how events that were centuries apart were conflated.

Immediately after that, the Bible describes the first murder committed by Cain against his brother Abel. According to the Edda, this murder is connected with the brewing art of the Heid. After the expulsion of those who had committed excesses, the making of intoxicating drinks remained in use or was resumed. However, it is also possible that this murder took place before the expulsion and that it was one reason or the main reason that led to the expulsion. According to the Bible, however, the murder took place only after the expulsion had long since occurred. Through the drinking of intoxicating beverages, tempers were now inflamed, and one word led to another, and from words came violence. This incident apparently occurred in the palace or great hall on the Himmelsberg, “in the High Hall,” which, due to the desecration from the murder, was set on fire and then rebuilt. The first murder mentioned in the Bible and the one in the Edda refer to the same event. The first murder that occurred on Atlantis was committed by an Aryan against another Aryan, thus by a brother.