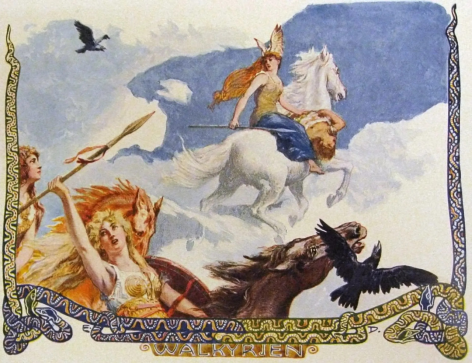

Consecration of the Valkyries

by Guido von List

To the high-minded, truly German woman,

Mrs. Victorine Wannieck

may this hymn of praise to German womanly virtue be dedicated.

From the author.

Once I journeyed as ferryman on perilous voyage, in the slender and fair-sailed ship, through the whirling waves’ surf roar, through thundering whirlpools of the Danube’s stream. Past castles and towering cliffs, by lush meadows and laughing shores, past sheltering sacred groves, until where a headland, shattered in cliffs, threateningly presses in proud grandeur up from the foaming, surging stream. There the nixies wrestle and never rest; the dreadful wave-arms dig deep into the rock, they strive to hurl down the defiant reef in raging assault. In between tremble the eerily hollow rolling whirlpools like restless eyes, encircled by brows of foaming spray.

With glances full of hate, full of roaring wrath, whether fruitless labor, whether joyless striving, howling they accompany with gurgling roar, to which joins the ghastly crashing and thundering, when mightily the princely rock hurls the waves downward, so that the nix, flung aside, boastfully rises again in woodland rage.

Thus it stands since ages steadfast and strong, amidst the envious horde of nixies, surrounded by the thundering surf’s din, in battle-bold majesty like a king. So it stood, as if just now steering the keel, guided into the boiling spray, when high foamed at the slender prow the frothy flood, lashing the flanks of the ship with resounding blows, so that the sturdy beams creaked and cracked, and the stately mast groaned in torment. With the wind at its side the boat storms past, into greedy whirlpools, and full of joy greeted the princely rock with foreboding rapture this consecrating word: “Be greeted, rock! Noble image of the Germanic people in the struggle of nations exalted! Like you, surrounded by envious neighbors, strong it stands and proud in the onslaught of storms full of noble grandeur, powerful against the yelping of the small. Thus you tower in menacing defiance against the pressings of the never-tiring nixie hosts. Therefore receive my greeting, you, glorious stronghold, you sanctuary of ancestral strength, from the ship on the Swan Road!”

Then through the spray of the surf-beaten reef there roared a song, like Æsir-song from the air. It resounded as if the clouds sang, the waves, the world-lonely meadow and the rigid stone, as though the sun in heaven’s heights had sung it, as though it surged from the depths, from the shadow of shafts. And free of all will, guided by song, I turned the rudder in swift movement and lowered the sail from the gaff. Onward the ship shot through the breaking surf, and island and boat lay side by side.

My foot ascended the steps of the rock, and swiftly was the towering peak attained. There sat an elder of noble bearing, his head covered with a mighty helm, from the full flight of the noble eagle loftily overarched, the high-vaulted broad breast in splendid armor. The curved shield, the gleaming battle-sword lay at his feet, and leaning idly a massive spear against his mighty shoulder, shining in the blue light with blazing brilliance.

Two ravens circled with whispering call about the noble head of the high hero, and two wolves with triumphant howling encircled the knees of the mighty warrior; yet never did they dare, despite wild fury, to break the fetter which a mighty will had laid around them both, to bind them both. Now he lifted his head. His flaming eye cast down, almost burning its way into my soul, so that my breath grew heavy, my pulses halted, then feverishly they flew again. Once more a torrent of fire swept the rigid body from heart to head, so that the trembling breast seemed near to bursting under the spell of oppression.

“Banish your fear and draw near, Runeward!” Thus cried the mighty one, naming me with riddling names in whisper, kindly to me: “Not feared by the Æsir is the old king, scarcely known any longer by his people, though faithfully he still leads the paths to Valhalla, despite his banishment. Fearless still stands a world in arms, the noblest-guided of all nations. Yet nevermore can it combat the treachery of the creeping poison of slippery serpents, that gnaw and rage at the marrow of the root, shamelessly fattening upon the mightiest folk.

The fiercest foe my people overcame, and never could thieving Rome in fetters forge the Lady Germania! Parthians and Greeks, Gauls and Britons bore the yoke of bondage, but my Germans pressed as avengers into the gates of Rome and toppled the throne of the proud Caesars. Thus there approached the Germans, in the press of envy, Avars and Huns, Tatars and Turks, Magyars, Mongols, Frenchmen and Slavs, and no people of the earth, however joyful I see them, can one name that would not in daring battle have been defeated by my Germans! But stricken to death, Rome emerged from the furious destroyers; with treacherous cunning, after heavy sickness it crept across the Alps to beguile the nations like a carnival play, disguised in hoods, with cross and crozier. And what it never won with weapons, that was granted it in this transformation! Still I hear the clinking and rattling of chains in which disgracefully my people languished. Still burns the brand-mark of Canossa in the heart, still is the wound of grief unhealed. And already vile agitators threaten again to strike my princely people to the core with bitter poison, to pervert the gifts that gracious gods bestowed upon the land. But never, in daring contest of wave-battle.”

With whirring sword-stroke did the cowards dare to wrest from the faithful people their goods. They came sneaking on smuggler’s paths, with filthy haggling, full of deceit and treachery, to snatch the fruits of labor with greed. Neither sword-stroke helped them, nor heroic deeds; the skald alone with words of warning, with inspired song, healing can be wrought here, enflaming the people to liberating deed! So hear then, Runwart, Herian’s whisper:‘Take this rod, carved with runes, the rod of wishes, to you gives it the god of desire! It opens all the guarding hill-doors, gives tidings to you from vanished days, and treasures you shall lift in wonder, that lie hidden, sunken in the sheltering rubble. My face I raise from Asahome, longed-for knowledge awakens for you. As Runwalt I consecrate you, Runwart, in faith, so wield the rod of desire. Understand for me the runes, unravel the staves, the strongest, most steadfast staves. Primordial speakers carved them, primal gods engraved them, the head of Asa cut them for you!’

Vanished was Wuotan. Thunderstorm’s sultriness lay on the land. Flashing bolts shot through the clouds in jagged turmoil, rolling thunders in resounding roar clattered, bellowing, to the surging surf. And howling the stormwind whistled around the treetops of the groves, the jagged spikes of the reef. A thunderclap boomed, it woke me mightily from rigid stupor; I strove, groping, to reach my boat, which soon I attained, to hastily steer the keel away from the isle through wildly disheveled, shattered waves, to flee the storm in hastened flight.

The green eyes of the nixies grinned maliciously at me, and nixie-arms grasped greedily at the swaying ship, to hinder the voyage, treacherously to drag it into the dark flood, to the dreadful depths. Heavy was the struggle with the daughters of Ran for boat and life; ever mightier they hurled their raging wave- and weather-powers against the boat in the foaming stream. My eye spied the near shore, yet it showed me no path, no track, no road, no house, no yard. Only in the distance I beheld rigid rock, and pine trees dark with dampness revealed themselves all around to the searching gaze.

Hissing poured down the rushing rain from frenzied clouds of rolling billows. Howling, the stormwind whirled the waves, the jagged gorge of the rocky pass, and roaring broke through the dreadful surf, wild in tempests the raging storm, so that the air mingled with the surging waters and wave and cloud became as one. To defy the storm with sail and rudder, to complete the voyage as lone ferryman, seemed never possible. Mightily urged the darkening twilight to make land before the envy-joying night destroyed all hope of near salvation from the nets of Ran. My eye spied the rocky shore.

With anxious searching through the crumbling rocks, at last joyfully it found in the rigid stone, close above the roaring, crashing surf, that in the rock there opened the dark maw of a shielding, shelter-promising cave, offering refuge for the night’s necessity, and wretched bedding on clay and rubble. Gladly I steered my boat through whirl, through waves, and soon the perilous voyage was ended. Already crackled and snapped in the gnarled pinewood, in abundant brushwood, quickly I gathered the flickering flame. Flickering it showed in reddish glow the spaces of the cave. Thinly flitted like hastening shapes the shadows and lights along the walls, hiding in crevices and wide clefts, then again appearing, growing in size, on surfaces and pillars, sometimes broad, sometimes broken up, in hundreds and hundreds of confused images. Now forming into hideous grimaces, then again resembling dreadful demons, the whirling shapes like threatening specters from vault to vault in ghastly circles swung themselves, fluttered about by bats and ugly owls, which with shrill cry flew round the fire in fearful flight to fend off the hateful guests. I seized the Rod of Wishes — O wonder! — what transformation, what magical end!

To a blissful hall the cave expanded, beautifully adorned with delicate carvings. The ceiling rested on towering columns of gleaming marble, mighty arches vaulted over doors and wide windows. Between them stood rich seats up to the high seat in splendid splendor, as worthy as that of the mightiest king. And awe-filled wonder seized my senses, as I saw the hall alive and filled with noble heroes and lovely women. In radiant glory also the princes of the people, and with golden diadem, as fairest adornment of the noble hall, his gracious consort at his side. Yet all were silent! Then with the rod I drew the magic circles, and without delay resounded the magic song: “With a name you once called me, since then you have led me to the peoples. But Wuotan, as Runwalt, the Rod of Wishes to me Runwart you handed down in whisper. Shone upon me the countenance from Asa-home, desired knowledge awoke. You unriddled the runes, revealed to me the staves, the strongest, most steadfast staves. Primordial speakers carved them, primal fathers cut them, you, Asa-head, carved them for me!”

First Song.

Ruodegar.

Ruodegar, son of Ruoperath, sat in the hall. The heroes and warriors in noble ranks, on benches all around along the walls of the hall, the mead-horns filled, yet of sorrowful mood. No bard praised with resounding song the glorious deeds of famous forefathers. No minstrel drew from the merry fiddle joyous tunes, no drum, no pipes called enticingly to the laughing dance. Only gloomy brooding and anxious fear lay like a nightmare upon every spirit.

How blissful it had been in the age of the ancestors, when not yet the envious, plundering Rome had raged in the land like hateful wolves, when still the mighty domains of men resounded with the mighty horn call through the woods, to a heartfelt campaign, to joyful hunt, and lively men in defense and arms answered the call with Hoihoh and Heiló!

Surely the Romans have gone homeward with meager treasure gold and the dreadful shrine, in which they bore the dead Roman, the Severan woman, her last guardian. The people were freed from the dreadful foes, but more dreadful still loomed the Hunnish horde that terribly drew near to the Noric land. Far more horrible yet than the approaching horrors raged in the land like wild lions, the warring tribes of their own people, destroying themselves in senseless strife of envy, instead of standing united against the looming storms that mightily encircled Germania.

The mighty will of noble Odacher had defeated the last Caesars, and gloriously in battle won the Roman crown for Germania, full of manly pride. Yet at home by the Danube, there ruled treacherously, as under-king, the powerless Onoulf, Odacher’s brother, full of arson and robbery. After being driven out from Chermis’s fortress, the last king of the glorious Rugians, in furious feud he fought the Goths. No less Lamisso, the mighty Langobard, hurled himself with robber’s might upon Ruodegar, the Harlung ruler, and overcame the proud one, and broke and burned down Bechlaren’s castle.

In the Noric land peace never blossomed again: the seed of peace in joyful bloom all too soon was smitten to the ground. Fields were laid waste, cities destroyed, broken castles bore the wounds that mad raging had struck upon the land, so that fulfilled seemed the vala’s dreadful prophecy: “Now brothers strangle brothers and become murderers, siblings plot the ruin of their kin. The grounds resound, greed flies: not a single man will spare the other anymore. Terrible treachery desecrates the earth. Time of axe and sword, of shattering shields, time of storm and of wolves before the fall of the world!”

Thus had fled with few men, after Bechelaren’s fall, the prince of the Heruli, to where in the forests the Harlung fortress offered protective shelter to the shield-warriors. Still he was king! What pitiful name, when power is taken, when secretly by night the loyal ones gather for sorrowful counsel, when the mead-drink lacks the flutes and fiddles, encouraging tones, joyful song. Sorrowfully they sat so, king like warriors, silent in the hall. Then spoke the shield-bearer: “O noble warriors! Onoulf has robbed me in deceitful defiance through treachery and council, despite all oaths and sacred pledges, of inheritance and treasures, land and people. The hall is emptied, the stables plundered, the cities burned, the castles broken, the herds stolen, the fighters scattered; yet king I am still called! — To sorrow yet scorn!

You few brave ones, who still swing the sword, who secretly creep to murmuring council, sneaking on hidden paths to trick the throne-thief, at night the rogues may near the hall to you. Spare your lives for shining death in battle! And tread the ways of watchers and warners, to bold Quadi and mighty Marcomanni, arouse the united eagles to vengeance. But I, your king, I choose this misery! Aimless I wander as a roaming fugitive, directionless with you as watchers and warners, for never shall Ruoperath’s son bow as vassal to the shameful, ignoble Onoulf.”

Thus spoke the king. The counseling warriors were silent and pondering. They hid their brows, pressed in their hard, sword-calloused hands, yet none dared speak in words how their hearts ached with grievous sorrow.

Then arose from his seat the old Sintold and spoke thus to the helpless host: “True it is and wise, how the king has decreed! Beyond the Danube in the March lands, bound together into one princely people, are Quadi and Marcomanni through bold battles. Never do they yield the lord of the Heruli, the ruler of the March-men’s domain. To seek aid, even to wield the sword at his side, diminishes not — so I deem — also not the honor of our dear king. For King Agilomar is of the noblest lineage and full of aid with counsel and with deed.”

The tormenting sorrow that consumed Ruodegar’s soul, to lift the gnawing grief from his heart, to the poor king the old man began: “Still harbors your spirit, my lord, many heavy cares you conceal. Though we may be too weak to dare a wave-battle against the torrent of bristling swords, yet are we mighty enough, O protector, to share in loyalty all your cares with you. So reveal the grief, O king, that torments you. Even if counsel cannot help nor find healing, still does a compassionate heart lighten the burden. So grant us, your faithful ones, O king, the solace of sharing your pain, when whispered counsel avails nothing.”

The pale king looked up in sorrow. He would not betray the secret of his heart, yet neither would he wound his men through silence. Therefore he resorted to deceptive cunning, and spoke thus to Sintold, the elder: “My thanks I give you, dear ones, and all you nobles. Therefore I will not conceal what grievously afflicts me. So hear then, my good men, the cause of my grief: in the holy harug, the sacred grove, at the foot of Cotwich’s hill, there springs a fountain, the maiden’s well of Lady Hulda, where lately the knowing vala laid the lots for me. As offering I consecrated a delicate goatling. It was indeed a meager gift, O poor king, I could not offer a horse as sacrifice, for war had robbed us of horses and children, herds and homes and hoard alike!”

The hag-Idise, the knowing vala, she slaughtered the goatling with downy fleece of softest wool and snowiest white, sprinkled with its blood the bubbling fountain, the broad beech tree and the mossy stone. Then drew the priestess its tender fleece away, spread it out before the beech upon the ground, and placed, as is custom, her foot upon the pelt. Thus consecrated, to dare the healing oracle, now she cast backwards in sacred order carved runes to the edge of the fountain, and once more drew at random the staves. From them she read to me with shuddering awe the lots of fate.

Thus sang and spoke the knowing vala in runic riddles the aims of the future: “Victory-songs sound in the holy grove; forged are fetters, the host is held back! Brave king, a Valkyrie chooses — thunderous castle-fire — bar of fate. Victory-songs sound in the holy grove!”

Silent and dismayed stood the loyal ones around the Harlung king, as the grievous tidings had just been told. No counsel they found, and pondering no comforting words, they lingered long in heavy silence. For all men knew that no one could turn such a dire prophecy to salvation. Long had Ruodegar’s speech ended, yet still the nobles remained in silence, when swiftly from Golfe Gëro, the doorkeeper, rushed into the hall: “To arms! Raise the helms! Shields are buckled, swords are drawn, the Hunnish dogs bark in the thickets!”

“The time has come,” cried the battle-bold king. “Cast fire into the beams of Harlung’s burg, and forth through the marshwood that shadows the castle. Then ride the gorges in tireless haste, and seek the paths to Burodun’s burg! No son of a Hun sinks gladly in the swamp, and if one does, may we gladly grant it him. Those who know the secret paths may escape the robbers in fog and night. So ride salvation and guard yourselves bravely!”

Then the noble Harlung heroes regained their word and their resolve: “We shall never abandon you in grievous plight. You have been to us truly in fortune a god. Therefore we stand by you, with our contending swords. If we fall, we fall, as Wuotan wills!”

“No!” cried the king. “No salvation comes from battle! Bravery, I believe, is wise action in helpful deed, not useless perishing in slaughterous strife!”

With wild woe the Harlung ruler seized a torch and hurled it, blazing, into the rafters of Harlung’s hall. And then a second, in reckless defiance, he thrust into the straw, that in thick layers covered the roof of the adjoining house. Full of horror and dread the Harlung heroes beheld the deed of the daring throne-lord. Yet he turned to his brave ones and spoke in farewell this proud word: “Already the flame licks the straw-yellow roof, beams and pillars collapse in the blaze. Into ashes sinks the ancestral hall, the proud hall of the sons of Harlung. To the ground bows Harlung’s burg. Therefore mount, O noble warriors, let each man choose his path, to ride upon perilous refugee tracks as watchers and warners for future battles! Farewell, you heroes and battle-bold men. So wills Wuotan, the ruling lord of battle, who now unites us all in the raging wall of fire to immeasurably mighty slaughter of men!”

Still stood the proud Herul heroes, spellbound by the king’s mighty will. Already crackled and roared the greedy flame around gables and halls, from roof and rafters, and glowing brightness shimmered through the night. Already crashed down pillars and beams, then stormed the Harlungs out of the hall to find their steeds for flight’s swift ride.

Ruodegar, however, the ruler of the Heruli, passed through the collapsing chambers of the burg to rescue from Pallas’ consecrated halls fair Walburg to his wounded breast. Howling surrounded on rough steeds, dwarfish riders with twisted beards and pointed skulls and crooked limbs the Harlung burg engulfed in flames.

Second Song.

Walburg.

The echoing hoofbeats of Hunnic hordes resounded with dull, threatening thunder in the rustling leaves of shady beeches. The Krajân-fires, like ghastly craters, flared with flickering cries of fire through Noric districts. Gnawing grief and choking rage stirred in the people, yet the end of bondage had not yet come.

The great and noble of the Noric lands had sunk to vassals of the Huns, or languished, disgracefully bound in fetters. Most, however, lay covered as dead. The ravaged fields, many had fled. The remnant of armies, in disordered hordes, marched as plunderers, shamefully defiling, robbing and pillaging the weary land. The rightful owners of inherited farms, turned into serfs, robbed and stripped, were hunted like wild forest wolves. At last, overcome by endless suffering, or terribly desperate, embittered and enraged, they themselves became raging bandits.

Ruodegar, the noble Herul lord, could not bear the shame to behold, nor ever in hidden defiance to carry golden chains as a Hunnic vassal. Fleeing, he left the lofty halls—the mead-hall, the free heritage of ancestors. Himself, he cast the burning brand into the trees and beams of the fortress, and as it roared and crackled in fiery splendor, the licking flames shot up to the gables. Crashing down, the halls of the stately court collapsed in dreadful blaze, falling prey to the joyless feast of Loge’s brood, the greedy brood of fire-devouring flame. Until all the warriors stepped forth alone, then he too departed—once lord of men, now landless fugitive, on a fleeing steed out into forest-shadowed paths, encircled by the blazing brand of the fortress.

Before him in the saddle sat the princess of peoples, his dear wife, the beloved Walburg. Stolen by enemies was the princely inheritance. Burned was the noble Harlung fortress. Left behind were all the gleaming treasures. Ruodegar had only his dear Walburg, his whirring sword, and his swift horse. Through moors and moss, through groves and heath, through gloomy forests’ dusky twilight, through craggy passes and rigid stone, through wild rivers and ravaged fields, led perilous the fugitives’ path of the weary wandering Harlung hero, until a sheltering hall rose as refuge, barely sufficient for the landless king as harmless hearth. Thus the cave became the Harlungen’s hall, consecrated by King Ruodegar’s will.

The forest offered game, the chase provided, the bold king with mighty throw. The spring refreshed the parched lips, and berries and mushrooms and potent herbs, also wild honey, granted the wilderness, so that never did want threaten the lost joy of better days. The shaggy bear’s soft woolly coat gave clothing and beds to the exiles. Hanging before the cave’s entrance, it held back harsh storms in wonder. A mighty fire blazed within the spacious cave like the home hearth, and bravely there Walburg nobly managed the simple household, alone and swiftly, that once, surrounded by women and maidens, she ruled in kingly hall under crown.

Thus gradually faded the horrors and fears that at first the wilderness, the grim banishment, showed to the Harlung lord in form. He felt himself richer than the most famous prince, for such a treasure, so noble, so sunny, he could only now in fullness discover. He could only now so wholly call his own, to recognize and cherish his brightest joy, to devote himself in all things alone to it, to consecrate henceforth his work to it. What were now to him people, friends, or foes, since Walburg grew to him as highest bliss—she who once in the shimmer of princely honor seemed to him only half so radiant?

And she was queen alike, the dear Walburg; so she is today, yet only to him alone. Were she a rose, or were she a swan, she would be queen; and shining in stars she would first glow as evening star. But no! Then must, at envious cold morning, fade her radiance—more dazzling, more glorious than the rosy glow of May morning appeared to the king as his sunniest joy! So grew the king’s love for Walburg and drew its golden magic circles around Ruodegar’s heart, so that the Harlung lord rarely thought of the oaths of his throne.

As agitator and warner from court to court, he walked the paths into the land of the Marchmen. Thus it once happened, that on a wild forest path, as Ruodegar hunting pursued the tracks of a mighty ursine beast, a band of robbers encircled the valiant hero. They blocked his way, with wild mockery derided his bright weapons. Then he would never have withstood the greater numbers. But the Harlung hero did not heed the pack. A grim throw struck the first; a firm blow toppled the second; and mightily trampled the third, with wild urging, the steel-hard hooves of the stallion. The rest, in frantic flight, trembling with fear, paid ransom for their lives, and howling, cursing, fled the Harlung.

Ruodegar gathered new arms and weapons, manly ornaments of brownish bronze, the rings and bands and clasps of the slain. And homeward he rode to the towering cave, where the beloved Walburg awaited his return. Tenderly embraced the battle-bold prince his dear wife and pressed her to his heart, speaking these words:

“I give to you, Walburg, to you, beloved spouse, this shimmering sword with sharp-honed double edge, which I took from the villain who wielded it in shame with robber’s comrades against his kin, while violent Hunnic hordes massively depopulate Germanic lands! I sent it to Hel on wind-cold paths. In their galling, seething blood I gave gleaming shine to the flashing blade, and now I wish that its mighty guilt of battles and slaughter-flame be consecrated to you, worthy one, my chosen joy—you, most noble guardian of divine fortune!

The rings and bands and shining clasps, the whirring battle-sword, they adorn you, tender one, as proud ornament—you, man-brave princess of the people, who endures without complaint the curse of princes, the banishment to wolves! Worthless to me now is women’s adornment. For you no more—only warrior’s state becomes you, free, fearless princess. For like a Valkyrie you choose the ways to Valhalla!”

Like the fire of the sun in radiant flames, reddishly gilding the towering peaks, mighty mountains, as if rising from clouds, seeming to lift themselves to heaven’s heights, so was transfigured with noble glow the noble princess of the Harlung folk. She seemed to transform into a shining goddess, as she raised her golden-locked head and lifted the flaming sword toward the sun. Her breast surged high, like storming lightning flamed from her blue eye, and thunder-like roared her speech from the heart:

“Hear me, Ruodegar! Hero in battle, hero in renunciation! Zio has sent you the victory-boding sign. This shimmering sword as light and beacon! Already I see it gleam in proud ray—the mighty Germania’s morning sun. Already I see in glowing, smoking dawn the hosts of ravenous Huns perish, and gloriously arises a sunlit people, which, mightily as a flood rushing south, opens paths eastward and westward, and easily gains wide lands. Already I see, divining, the ranks. Despite envious gnawing of vile foes, the fruits ripen on the tree of the people, granted to the Germans by gracious gods. The foes fall, and victoriously rises a mighty Germania from the seething blood-smoke!

Hail to you, Ruodegar, raging hero! Hail to your southern march in streams of swords! Go forth with the sign of Zio, weighty and wise, to the council’s rulers, as solemn call to manly, united deed!”

Walburg wavered, sank exhausted into Ruodegar’s arms. She, a seeress, looked into distant, fair days. But blinded by flashing, radiant light of heavenly distances, her senses failed of the mortal woman’s body. The wonder-stars of her blue eyes closed in pain, until, accustomed again to earthly dark, she raised her lids to greet, in love, with friendly glance her princely husband.

The knowing counselor of runic riddles now listened to Ruodegar’s loving advice, who gently embraced his faithful wife, tenderly swaying her on mighty knees. “Do not trust, O beloved,” Ruodegar spoke, “in deceptive play of comforting dreams. The time is not yet to march forth on hidden paths, demanding the army. Scarce could the meager, small host of the Harlung force withstand the countless Huns in battle behind stones and trees in forest ambush. A pitched field-battle with Huns prudence forbids, as even Wuotan forbids useless slaughter.

Wiser, I think, it is to endure without complaint, till once more healed of hardest wounds my sword-strong people. While the fearful Hun dreams himself secure in careless peace, and the sly stranglers rest in slumber, then it is time to encircle the oppressors, to kindle the flickering flames, that shining, blazing holy fire might grow into a surging wall of fire, terribly kindled into raging world-blaze, devouring the dreadful foe. From Hutberg to Hutberg, from Harug to Harug, shall run the blaze of the Krajân-fire, as wind-swift messenger to banish the spell! In one day, in a thousand places, the flame of the weary land shall blaze, that terribly the merchants and carters cry out, terrify the courage of the Hunnic hordes.

The brightest flame, the flashing sword-light, shall encircle the faint-hearted with stormy might. Then we shall fall, victorious in proud slaughter, with inwardly flaming wound-fire, the battle-wolves raging in forest-wild fury! But today it would be ruin, my dear heart—ruin to the people, and ruin to you! In heavy hour you must forego my aid, my beloved. So let this warn you, that we prepare future as we proclaim it: the divine working of mortal woman, and divine action comes from human deed! So wait and hope and endure joyfully! And give me then a noble heir, ornament to the tribe, support to the future. So I swear aloud by Zio’s wrath-sign, as stealthy prowler from Harug to Harug, from court to court secretly to go, to stir the ferment to blazing fire, to heroic deed of Hun-destruction!”

Third Song.

The Birth of Schwertwart.

From soft, woolly, warming fleece—the pelt of the Walkönig Petzo, who once had snatched Ruodegar with life and limb from peril—had become the bed on which Walburg, with harmonious heart in heavy hour, bore a fair-haired, sun-blessed son. Ruodegar, bending joyfully, lifted him up, thanking tenderly the gracious Hulda.

For months the skillful mother had chosen wax from sorrowfully won honeycombs. From it carefully she formed the magic candle, bound with twisted, tender bast of rushes. At waxing moon, with whispering murmurs and many a strong magic word spoken, she carved runes with anxious care for the helpful healing of the child’s candle, which now burned by the bedside’s frame. Most holy herbs, full of sacred power, consecrated beasts chosen for sacrifice, the happy husband and princely father devoted in reverence to the eternal Æsir at the hearth of the cave.

The lone-born, blond noble child was named Schwertwart by his sword-bold father, and carefully guarded by the sun-honored, loving mother. He thrived and flourished, and in growing strength became a sturdy lad of noble parents—the happy couple.

As restless Yuletide rolled the year, sunk in the stream of passing times for the loving pair, brightly shone again the sun on the same spot of the blue sky from which it gleamed when Schwertwart was born the vanished year before. Then worry pressed the faithful shield-lord’s troubled heart, when he shudderingly thought of the painful vow which required parting from his beloved wife, his sunny son.

Walburg too lived in wild woe, yet she was equally brave and strong-willed, and dared, not delaying, with steadfast word to urge the dear one to manly deed. Thus passed away, clouded by sorrowful care, the second year too in the stream of time. And again there appeared, a warning of guilt, the day of birth of both together, for joyful celebration in loving union. Yet troubled was the mood; streaming tears the thoughtful princess strove to restrain, and shy to the wood slipped the Harlung.

And though neither had spoken aloud, warning and urging in meaningful word, both knew in anxious woe that the hour of parting in storm drew near. Then Walburg dared, conquering her heart’s harm, with steadfast soul and strong spirit, in cheerful tone turned warningly to Ruodegar, whispering to remind him of the manly word: to walk the path of agitator and warner, to feed the flame with princely freedom into bright, people-liberating fire.

With a sorrowful sigh now Ruodegar looked on his beloved wife, so manly of spirit; but sadly, full of dark foreboding, he spoke:

“My royal wife! How can I yet dare to walk the way of agitator and warner, when unshielded I know, in dreadful wilds, you—dearest heart—and sweet Schwertwart?! Who will ward off the throttling forest-wolves? Who will ban the bear’s marauding horde? When traveling far, who will guide your way? Who will protect you from the stately horned stag, the wild aurochs, the swift deer, and the herd’s flickering holy flame?

So refrain, O good one, from such mad reckless urging, before Schwertwart, sword of the sword, is grown strong enough to wield mightily with manly strength. And while waiting, shielded and guarded, for I know you safe in rocky stronghold, then Walburg, full of mighty will, shall draw forth the flickering sparks into blazing flame, swirling, with raging ropes, with searing gusts, to strangle the vile foe in radiant flame of people’s liberation!”

Well knew Walburg how hard it would be to overcome the fear of her own soul, to urge Ruodegar to glorious ride, to combat the husband’s wavering delay. She knew to honor his burning love, yet knew also to honor, to uphold, the high duties of the people’s princess. Though her heart quivered in her breast when she foresaw the coming woe, and always thought, shuddering, of parting, she knew unshakably the will of the ruling guardians of world-fate. Thus she bravely fought the pressing grief that gnawed within her wounded soul. With heroine’s spirit she overcame the doubts of her deeply concerned one with seeming defiance:

“See! These sinews and mighty muscles!” In excited speech the noble one cried. “Of bronze I seem to be formed, and scarcely could one believe a weak woman has hurled the heavy shaft that now whizzes and buries in the beech bark!”

Thus speaking, in passionate surge, she cast with mighty arm the great spear of the Harlung hero, in sure aim, with furious force, so that the gleaming blade bit the beech and the swaying shaft trembled deep in wood. Upon this, pointing with proud dignity, Walburg turned her word to the valiant:

“I am born to be princess of the people, to share in loyalty, joy and sorrow, with the dear one on throne, in dangers and need! This seems higher to me, my Harlung lord, than to be called only the joy of your love! Think you, I would not bravely dare to fight the pitiful bear, the whimpering wolf? Think you, the chamois, the stately stag, the swift deer would escape the throw from the iron arm of the lonely noble? I am the royal consort of the bold Heruler! Ride calmly to the roaring council, follow your noble ancestors’ ways—the world-famed path of agitator and warner. Walburg remains guardian and keeper of the noble heir, our kingly child. She shines as proud princess of the people, adorned in manly ornaments and gleaming sword-gear. And once again enthroned beneath crown, on lofty seat in princely hall, Walburg shall be with the people’s ruler—the mighty prince and leader of the hosts!”

With growing pride she looked upon his strength—the dear, noble, awe-inspiring princess, the battle-bold Walburg, his stately wife—whose glowing cheeks, in fiery speech, shone with noble transfiguration. Passionately the king embraced the heroine, kissed the brave one in joyful sorrow. Then he tore himself away, and spoke thus:

“Now I am calm and ride to the council of glorious avengers of ruthless Huns. The magic-laden Zinklinge adorn yourself with, loving, tender mother—you wondrous great one, you divine wife! Your dear, smiling, radiant face, may it shine like guiding star on joyless paths of adverse fate, hovering before me as blissful vision, like Freyja’s veil upon my secret way! Guide and guard the boy wisely, you best of mothers in loving care. Wait and hope, till back to the hall, to renew your joys, your honored husband shall bring his son, his beloved wife!”

Another kiss to wife, to child—and Ruodegar, on swift, raging steed, rode forth from home, the cave that held them, to stir the flames of people’s battle. —

Fourth Song.

Walburg’s Death.

Long still did the loving Walburg listen to the fading sound of hoofbeats on hard earth. Long still she waved to the shining hero, to her dearly beloved, the noble one in thought, until envious brushwood, twining vines, alder and oak, hid the Harlung lord from the eyes and ears of the noble lady. Tearful-eyed she sat alone at the entrance of the sheltering cave, with anxious heart—the foreboding Walburg. She who once ruled, surrounded in splendor by merry maidens, by lively women in Harlung’s high-burg, was now banished in concealing wilderness, to bears and wolves, to roaring winds. Deprived of all, a sacrificial offering as princess of the people—yet she felt it dreadfully as loving wife, as tender mother. It was so hard for her, the parting from her godlike, caring, battle-bold husband.

She concealed her fear in her sheltering breast. In her grieving heart she had bravely, yet painfully, withstood the spring of tears; but now that he was gone, downward flooding the tears streamed flowing from the well, releasing her soul from searing grief. To her beating heart she pressed the dear boy, caressing and kissing, lovingly laying him. She lifted her bright eye to heaven, still wet with the flood of sorrow’s tears, and with strong, steel-clear voice singing, over forests and ponds, meadows and rivers, sounded her fearless song of consecration:

“Hear then, you noble, most holy gods,

Walburg’s fearless consecration-song, her magic-song!

Runes were carved

By knowing women,

Haag-Idises,

In faithful service

Of the eternal Aesir;

They guarded the knowledge

From ages primeval,

Foretelling the deeds

Of great-gracious gods,

Who rule the universe,

Whirl the clouds,

The salty sea,

The devouring flame,

The groaning storms,

And the Midgard serpent,

Strong enough to bridle

In anger,

With fate-forging,

Most holy hand.

So hear then, you noble,

Most holy gods,

Walburg’s fearless

Consecration- and magic-song:

Blessing and woe,

Ruling Wuotan,

Is Walburg’s wish—

Grant it, O Mighty One!

I know how you hung

On the wind-cold tree

Nine eternal nights,

Wounded by spear,

You yourself, to yourself,

To Wuotan devoted!

I know how you grew

And became wise

Through wishing word:

In rune-ring,

By spell-forcing,

Your wish grew

From wish to will,

From will to word,

From word to work,

To world-awakening

Heroic deed!

So will I consecrate myself

With wish and with will,

With bold defiance,

To you, ruling Wuotan,

Brave as a Valkyrie!

Grant it, ruler,

Guardian of the hosts!”

“So hear then, you noble, most holy gods,

Walburg’s fearless consecration- and magic-song:

Freed from the burden

Of the woeful body,

Let the Valkyrie choose

On cloud-ways,

Joyless, painless,

Walvater’s hall.

Therefore, gracious Hulda,

Lift away

To harmless home-folk

My royal child,

And later grant him

A renewed, useful,

Light-filled life,

When, demanding freedom

From shameful fate,

Germania one day shall honor

A power-proud king,

Who mightily shall break

In days far to come

The treacherous tyrants’

Torturing fetters,

The dishonoring yoke.

So hear then, you noble,

Most holy gods,

Walburg’s fearless

Consecration- and magic-song:

You, fire, then roar

In blazing flame

Through Germania’s marches,

With flickering fire,

Crackling breath,

Storm yourself down

On wicked robbers,

On wicked Rome,

On Hunnic hordes,

On cowardly Byzantium!

For warning and stirring,

Fate-shaping,

I have mightily bent

The will to battle

Of my husband.

So hear then, you noble,

Most holy gods,

Walburg’s fearless

Consecration- and magic-song:

Blessing and woe,

Ruling Wuotan,

Is Walburg’s wish—

Grant it, O Mighty One!

Let me guide

Ruodegar, the Avenger,

Me, the power-joyful,

Rune-unriddling,

Rune-mighty,

Cloud-riding,

Knowing Valkyrie!

Let me guide him

To proudest victory;

Let me choose him

For fairest battle-death;

Let me call him

Einherjar hero,

From seething blood-smoke,

From raging battle!

And when crackling the fire

Through rustling brushwood

Sends its greedy flame

To weave the wavering mantle

In fire-golden splendor

Around the dear dead

On fir-wood throne,

Then let me, loving,

Embrace the leader

Of the princely people,

Let me lift him

To lofty bow

Of the cloud-horse,

Let me guide him,

Show the ways

To Walvater’s Valhalla!

Grant this, O Wuotan,

To the future Valkyrie,

Who worthily consecrated herself

With child and with husband

To you, guardian of the host,

As you once consecrated

Yourself to yourself!”

Then she turned her gaze toward the sun, radiant, shining, with holy exaltation. The child at her breast, sheltered in her arms, the noble Walburg stood in radiant beauty, transfigured as though one of the Asynjes themselves, awaiting with dignity the god’s granting.

Now twitched the tousled, heaving clouds, coiling like threatening dragons around the rolling wheel of the sun. Like skulking shades in slinking creep, like mangy hounds circling the hunter, dodging the lashes of the whistling whip that striped their backs with bloody welts. No, they did not fear—the approaching shadows, sneaking in twilight as nearing clouds, darkened the sun with dimming veil, covered mountains and castles, forests and waters, hid the laughing land in sullen gray.

Now howling, roaring, with snorting and puffing, the storm-wind rolled in furious rage, chased by the hounds, the wind-wolves of Wuotan. Howling, whining, with shrieks and barks, they tore forests and rocks in wild frenzy, snapping branches, toppling trunks, splintering firs and pines to ruin. On gray-cloud steeds in rushing ride the Valkyries followed the panting hounds, spurring the gray mares with shrill cries, so that whinnying they reared in wild hunt, foam from their bits streaming in showers as surging torrents swept the fallen trunks.

The clashing of chains, the rattling of rings, the shrill cries of grim Valkyries, the wild neighing of cloud-steeds, the thunder of hooves, the whips’ whistle, the storm’s raging, the hounds’ howling, the hail’s drumming, the thunder’s rolling—all mingled into marrow-shaking uproar. Even the cheerful finch, the lark, fell silent; all fled, for from heaven’s height sounded the voice of the Ruler with might.

Only Walburg knew Walvater’s will. Fearless she stepped into the dread tumult, her child in her arms, soothing, kissing. She looked upon the terror of the skies, saw Valkyries spearing through the storm, heard their roaring, thundering magic song:

“We choose you, Walburg,

By Walvater’s will,

To sisterhood—you, weak,

You, mortal woman.

Your life shall end,

Freed from the fetters,

Step forth, O pure one,

From the thorny path.

Granted are wishes,

Your will has turned them

From wish to word,

From word to work.

So mount, sister,

On the smoke-gray steed,

To restless riding

On cloudy ways!”

The blissful Walburg, radiant, fearless, heard the granting of her wish in mighty words. She pressed the boy to her heaving breast. Then, flashing, Walvater’s Gungnir flew—the god’s spear in heavy throw, piercing mother and child together.

Crashing trees, falling stone and dust covered the remains of the consecrated, shielding them from wolfish desecration. Walburg now rose as Wuotan’s Valkyrie, as youngest sister of battle-maidens, riding the storm-clouds to Valhalla’s hall.

The howling ceased; the storm grew silent. Rain fell softly, as Hulda lifted the child’s soul aloft in swan-feathered host, to harmless spirits, little home-folk. The sun broke forth again in brightness, the birds sang anew, the forest king Petzo once more licked honey, and peace spread across the world.

Now the rainbow arched flaming high—the Aesir’s fire-bridge, showing Walburg the path to Walvater’s throne in Valhalla.

Fifth Song.

Krajân Fire.

South of the Danube, to his loyal men, Ruodegar rode, the lord of the Harlungs. Disguised as a pauper, in the darkness of night, on wolf’s paths through the Harlung land, he carefully avoided the roads and towns. From grove to sanctuary, from hall to homestead, the king passed in secrecy, until at last he came on his riding steed to summon the nobles. With burning words he called them to mighty uprising, to vengeance upon the strangling robbers—the Hunnish hordes that ravaged the land.

The Harlungs welcomed their king. With heartfelt joy they received the hero, whom they had long thought dead or imprisoned, and swore anew, by shield and by sword, oaths of loyalty for deeds of liberation. Each noble pledged to provide men and horses as much as he could, also watchers upon every peak and hilltop. Great piles of resin-rich logs were stacked as beacon-fires, while scouts were set to spy the land. And so it was decreed that, when the Krajân flames rose blazing from the nearest mountain, each pile would be kindled at once in answer—a joyful call to the people’s uprising.

In the Noric districts, by Ruodegar’s swift and shrewd hand, the smouldering ember of hatred for the Huns was fanned to a bright flame. Veiled only thinly, it awaited impatiently the devastating outbreak. When his counsel had thus succeeded, Ruodegar crossed the river in a proud chariot. Once he had reached the other shore, he cast aside the lowly disguise, stripping off the concealing cloak that hid his byrnie, and stood forth once more as a battle-bold warrior on his swift horse. So he hoped to summon the Marchman king to bold alliance, and to declare that a levy of bright hosts would follow him when the beacon-fires proclaimed, with flames, the day of liberation.

Soon was reached Burodun’s burg, proud city of the noble Agilomar. A mighty fortress of manly Germans, it had once been a thorn to the Romans while their legions camped along the Danube, and now it stood as shining prize alike to Huns, Goths, Rugians, and Lombards, to be contested in daring strife. But Agilomar knew how to guard his jewel, so that none dared stir conflict against it. All sought rather his alliance, preferring bonds of friendship to perilous enmity.

The precious Burodun Ruodegar now approached. At the edge of the ditch he rode along, behind which towered, glowing red from fires long ago burned into the rock, the massive walls enclosing the warlike city. High in the air, upon its steep crag, rose the castle with turrets and battlements, its base unassailable by ram or ladder. Beside the towers lay piled clay projectiles, with mighty slings and heaps of pitchwood, ready to hurl fiery welcome upon any foe.

The watchman spied the rider and called boldly: “What warrior rides there before Burodun’s wall? Tell me, bold one, whose son you are, of what tree the blossom—are you friend or foe?”

Ruodegar answered swiftly: “Tell your king, faithful warden, that I come as king from the Noric lands, seeking and bringing aid. Ruodegar am I called, lord of the Harlungs.”

The warden returned with greeting: “Agilomar, king of the Marchmen and Quadi, sends you welcome with words and kiss of friendship.” Soon the oak gate groaned open, and Ruodegar rode into the city, through winding streets, past watch-hill and heroes’ meadow, up the steep climbs to the citadel where the high hall stood beside the sanctuary. At its threshold Agilomar himself greeted him, aiding him from his steed: “Welcome, Harlung king! Long have I missed the famed Ruodegar. Come in, refresh yourself, and tell your tale!”

Inside the golden hall they sat. The cupbearer poured rich mead from a twisted bull’s horn, and after deep refreshment Ruodegar spoke:

“My gracious host-friend and king! Long known it is how mightily you Marchmen and Quadi for five centuries have driven out the fiercest foes, so that never for long envious oppressors played lords in your halls or reaped harvest in your homes. It is otherwise with us in the Noric lands. Though still I am king—they dared not take all—yet by treachery my inheritance was stolen, my castles broken, my herds scattered. I would not bow as Odacher’s vassal, Rome’s servant. I chose exile rather than disgrace, for the Harlung ruler never bends. Then came the starving hordes of the Huns, and robbed what remained. Only wife and white steed, only sword and shield are mine still. But I have fanned the sparks of hate to holy flame in the Harlungs’ hearts. When the Krajân fire leaps from Burodun’s burg, that flame shall blaze from peak to peak as sacred war-call. Thus I offer aid, and ask it in turn.”

Agilomar answered: “Your aid, O Ruodegar, is welcome indeed. Long since have I resolved on the march to Rome. Though a German sits now on Caesar’s throne, Rome is still Rome—the strangling wolf, the dire oppressor of our people. Therefore I counsel this: ride to Rome, bridle the wolf, and bind him like cunning Loki. One under-king alone shall rule in Italy, wise and mighty, but loyal to Germania’s realm, that from her lands one high king may weld together a mighty whole. If you will, then rest in my hall, and spare the hunt for allies—they are already sworn. When the Krajân fires blaze from Burodun, the hosts will gather, and you may hold the war-muster at Heristal.”

So the kings bound themselves by oath and handshake to aid one another. Ruodegar thought longingly of Walburg, but held back from naming her—better she remain hidden in Harlung forest than risk her as hostage in another’s hall. Later, high upon the castle hill, Ruodegar beheld the beacon-pile, towering like a tree, drenched in resin, awaiting the spark. He foresaw in vision Germania united, born in fire at Burodun’s burg, rising above Rome itself. He dreamed of Walburg crowned queen, young Schwertwart at his knee, Germany’s hosts storming the Alps, Rome in flames, its walls fallen. Yet he also saw a pale figure, thrice-crowned, rising from the ruin, threatening Germany with chains and torment. But brighter still rose a star, banishing the shadow, promising hope and strength to the people.

Then Valkyries circled in the storm-wind, and one spoke prophecy:

“Know, Ruodegar, the fate of the Germans.

Three roots of guilt bind them.

Division—you call yourselves Saxons, Swabians, Quadi, Lombards, Alemanni—

when will you call yourselves Germans?

Foreign-lust—the second curse: despising your own, craving the foreign,

you weaken your race and kin.

Blindness—the third, heaviest root:

failing to see, until too late,

that at the abyss you awake only to fall!

This threefold guilt is your fate,

never to be erased.

Yet with will and valor you may fight fate,

and postpone the end,

until Germania falls with the world itself!”

Ruodegar was shaken. But that night came tidings—Ermanaric, king of the Goths, sent word that young Dietrich would march with them to Rome. Then the beacon-fire was lit, the night blazed with flame, and the German hosts gathered for mighty, liberating battle.

Sixth Song.

The Valkyrie

Destroyed, crushed beneath the wrath of the peoples, in the steaming reek of blood and smoke, Rome lay plundered and burned, like a corpse. Fallen were her stately soaring battlements, the gilded gables and vaulted halls; her towers burst, her gates broken, her lofty columns splintered and cast into rubble. Proud Rome, the capital of the world, stood judged—a city undone.

So once had the Harlung ruler beheld it in vision, the sword-victory over the world-city. And now, when in truth by the shining sun he looked upon that horror, the shaft had already robbed him of life and body.

A long procession of battle-weary warriors left the camp of the victorious Germans. Before them they bore a bier of gleaming shields, where Ruodegar, their king, was laid—the last to fall, pressing ever forward, who with dying eye had still beheld victory: the shameful flight of beaten Romans, the dawn of a splendor yet to come, of a people united, noble Germans. Then Walburg had crowned him, with a long and tender kiss, as Wuotan’s Einherjar.

Yet never would the envy-cold earth of Welschland cover the fiery lord of storms. Faithful friends, as Agilomar commanded, bore the fallen prince homeward, back to the far and sacred soil of his fathers, where above him the burial mound should rise. Kings, princes, warriors, the whole host, accompanied him to Heristal. There they placed the mighty lord on a high seat richly adorned, and about him heaped treasure-hoards as consecrated offering.

But still more was done. For by Agilomar’s will, Ruodegar was armed again in byrnie and harness, set upon his glorious steed, and with treasure-laden pack-beasts and noble retinue carried in solemn train to the homeland. Since forefathers’ days a sacred hill had risen there, out of the forest-rich valley, like a throne of clouds into the blue. On Herian’s hill Agilomar ordered the mound to be built, that all might know the grave of the fallen friend.

Upon the summit they raised the pyre—a gleaming fortress of shields, faggots bound with resin and thorn, crowned with a princely seat of fir. Upon this they set the king: the bossed shield, the byrnie gleaming, the mighty spear, the great helm crested with eagle’s wings, the flashing sword, flame of battle—all war-gear he was given, richest gifts for his ride through fire to Herian’s hall.

The hooves of his white steed too were raised upon the pyre, that he should not lack a horse in Valhalla. And bound around him they laid the bodies of captive foes, to serve him above. Treasures piled in curved shields surrounded his seat, that he might not come poor into the gods’ hall, but consecrated and rich.

Then the skald ascended the steps, consecrating the faithful steed which had borne its lord through storm of battle and whispered counsel, and which must now bear him through fire to Valhalla. With the shining sword the bard struck, and the white horse’s life ran red. Thus was all prepared for consecration.

But as the skald bent to kindle the fire, suddenly in whirling clouds, on smoke-gray steeds, the Valkyries circled the shield-fortress. From bright heaven a ray of light fell like a spark into the resinous wood. Crackling, roaring, the flames leapt high and wrapped the dear corpse in purple fire.

Silent, stunned, the host of warriors scarcely dared stir. No rune-song sounded, though custom demanded it. The steeds stood still, their riders rooted, spears raised, expecting no less than Wuotan himself for the last battle at Ragnarök.

Still the Valkyries circled. Still the flames coiled and the smoke twisted toward heaven. Then suddenly Walburg, upon her gray steed, rode into the blaze. Lovingly she embraced her husband, lifted the prince, and awakened his white horse, which snorted fire and foamed flame. With spark-showering hooves it thundered upon the pyre, and the victorious warrior sat once more proudly in the saddle. Beside the Valkyrie he rode forth from the burning mound. Behind them followed the maidens of battle, riding the cloud-paths. But foremost shone the pair, in radiant splendor through the blue, like divine forms freed of mortal burden, freed of the storms of joyless fate.

Upward they soared, swanlike, to Bifröst, the flaming bridge. Their hooves struck glowing crystal, the bridge thundered, quaked. Through the golden gate of the gods’ burg they entered, which rang as it opened and thundered as it closed. Only the last, the lame one bound among the captives, slipped within, struck at the heel, limping as reminder of mortal toil.

Behind them collapsed the pyre of the Harlung hero. Princes and warriors shoveled the glowing ashes, covered them with stones, heaped earth seven men high, and laid turf upon it. Thus was raised the mighty mound of Ruodegar. The people called it Ruodegar’s Horst, held it holy, and hoped that from it, in days of woe, the sleeping hero would burst forth with byrnie and banner, leading the Germans in the last battle, to guard them until the world’s end.

So believed the folk, and still believe today. In sorrow, when struggle presses them down, they lift their eyes to the high hill, and long for the rising of the hero—from Ruodegar’s Horst, the high Radhost, the Germans’ watch in Moravia.

Final Song

Abgesang

Once more the great hall arose, the Harlung fortress from the wellspring of vision. Again it gleamed in wondrous radiance, the fairy-tale image of the marble hall.

Beautifully wrought with delicate carvings, the ceiling rested upon towering columns of glistening marble; mighty arches rose above doors and broad windows. Between them stood rich seats, leading up to the high throne in splendid magnificence—worthy indeed of a mighty king.

And once more I beheld the noble heroes, the loving women, the song-bright bards, and in their shining circle the prince of the people, and with golden circlet, fairest adornment, the queen of the hall, the king’s consort.

But as in Briar-Rose’s enchanted hedge, so in the tree of sorcery the hall’s adornments lay dream-heavy upon the cushions of chests, leaning against pillars, paralyzed with slumber. Seated and standing, they seemed overcome by sleep, subdued by the force of the spell, tamed by the compulsion of enchantment—the brave and the fair of the king’s hall.

Were these mighty dreams of illusion, deceiving my senses with trickery? Then I thought of the whispering staff, the rod of wishes; and gleaming before me shone the runes, from twilight ages to show me the goal.

So once again I drew the magic circles with rune-carved wand of wishing, whispering, unveiling the word of desire: “Wielding Wuotan, to you I remain consecrated, in faithful service as skald forevermore!”

And once again I traced the magic circles, and boldly rang out my song of enchantment:

“By no single name have you called yourself,

Since you fared among peoples;

Yet, Wuotan, as Rune-wielder,

You gave me the wish-rod, whispering;

Your face shines to me from Asgard.

Desired knowledge awakens,

Runes are unveiled; staves whispered to me—

The strongest, most steadfast staves.

Primal speakers carved them,

The forefather engraved them,

You, head of the Aesir,

You cut them for me!”

Then a trembling shook through the hall. The pillars, the walls, the loft swayed. Into twilight shadows sank the warriors and women of the royal chamber, and once more the vast cave arched above me.

Darker and gloomier wrapped me the blackness; the last spark of fire sank with crackle into smoke. With effort the eye mastered the dark, and shuddering I beheld the spectral change.

For there, where the throne-lord had sat, I saw, with crown and sceptre adorned, an eagle. Around him, instead of heroes and women, circled falcons and ravens.

But the spell of silence was broken, the magic of sleep undone. The kingly eagle spread its wings for powerful ascent, and falcons and ravens shrieked about him as he strove for freedom, wings lifted for the flight to the sun.

Compelled by breathless wonder, I followed the winged host to the cave’s exit, the wand of wishing in my hand. And there gleamed, in golden light of the brightest sun, the glistening river, the jagged peaks of circling cliffs, the ferns and pines of headlands and bays, and above all arched the blinding eternal blue.

Down toward the river’s mirror the eagle descended. From his head he cast the radiant crown, and sceptre and treasure sank into the stream. Whispering, rushing, the waves rolled over in golden glow; a shining flood, and clear to the bottom my gaze followed the sinking hoard of the eagle—now faithfully guarded by the water-maidens, the nixes of Lady Isa, who singing and telling in wave-song proclaim the tale of the Harlung Hoard.

High toward the sun the eagle soared again, falcons and ravens whispering about him, toward the roaring high flight, to Ruodegar’s Horst.

* * *

And I boarded my ship, steering as ferryman, to follow the track of the Nibelung’s sons, to journey onward along the Swan’s Road, as once Lohengrin, to the holy Grail.

End.

Afterword

No people on earth—neither of ancient nor of modern history—has lived through so glorious a youth as the “most nobly-princely of all peoples,” as the people of the Germans.

This radiance-filled blossom of youthful vigor, which scholars somewhat inaccurately call the time of the migrations, our ancestors themselves named far more fittingly their “Age of Heroes” (Reckenzeitalter). They celebrated it with enthusiasm in saga and song, depicting it as immediately following the age of the gods, and closely linked to it.

Thus, it is difficult to describe the individual figures of saga purely in the historical sense, even though they are indeed historical personalities. First, because they are adorned with legendary embellishments; second, because they are seldom described in the time of their actual deeds; and third, because they often appear in inseparable connection with persons and events which historians dismiss as error, but which the student of legend must, with equal rigor, recognize and preserve as the literary property of the entire German people.

For this reason, such legendary material is suited to the form of epic poetry (compare Jordan’s Nibelungen, Hildebrand’s Return, etc.), since epic does not have to meet the strict demand of “historical fact” in the way a historical novel must. The epic may shape the legendary figure, while the historical novel must remain bound to the historical person.

Of the many kings and heroes named in saga, most are historically confirmed:

1. Dietrich von Bern as Theodoric the Great,

2. Etzel as Attila,

3. likewise Gunther, Ermanarich, and many others.

But the personality of Ruodegar of Bechelaren was only firmly established by the highly deserving historian Professor Heinrich Kirchmayr, the “Paulus Diaconus of the Quadi.” In his History of the Quadi, he demonstrated that Ruodegar of Bechelaren was none other than Radagaisus, King of the Quadi, who with two hundred thousand men invaded Italy in the early fifth century, advanced as far as the Catalonian mountains, where his army, consumed by hunger and disease, was finally defeated by Stilicho.

Just as the Herulian Odoacer is bound in legend to many localities (Groß- und Klein-Otter, Ottensheim, etc.) as King Otter, so too does Radagaisus appear as Ruodegar of Bechelaren, bound to Pöchlarn, to the Harlungenburg (near the present village of Harlanden), and to the “Radhost” in Moravia. It is especially noteworthy that both at Radhost and at the Great Otter the well-known Kyffhäuser legend has survived in connection with the respective king.

The saga of Ruodegar of Bechelaren, the one of Radhost, and their relation to the historical Radagaisus—even though they are separated by more than a century—I have attempted to merge in brief epic form, using it as a background for the main portrayal of a Germanic act of self-sacrifice: “The Consecration of the Valkyrie.” For this reason I have painted the saga only in broad strokes.

According to the Germanic faith, the human soul after death had three different fates:

1. The souls of the good were immediately united with the deity.

2. The souls of the just were reborn for further purification.

3. The souls of the wicked entered the cave of mists, where they remained until the world’s end, to be reborn—atoned—after the Fimbulwinter, when the new, cleansed world would arise under the renewed gods, green and blossoming.

Thus, the souls of the good appeared only in Wuotan’s host or in the retinue of Lady Hulda. The souls of the just could appear to mortals as benevolent spirits until their rebirth. The souls of the wicked, however, deprived of the grave’s rest, appeared as ghosts or other hauntings, to their own torment and that of mankind.

To be united immediately with the deity after death, to escape rebirth, and to obtain from the godhead the fulfillment of a special wish, self-sacrifice was held—besides death in battle—as the surest way. This path Walburg chose: to compel for her husband, by magical means of womanly faithfulness, the highest good of German herohood—battle-luck, battle-death, and undying renown. To depict such magical devotion of womanly loyalty is the aim of my epic poem “The Consecration of the Valkyrie.”

On the Origin of the Tale

A word on the origin of the frame story, found in the Prologue and Epilogue, which is linked to a voyage on the Danube in a gig.

In the early 1870s we traveled from Passau to Vienna, intending not to stay at any inn or eat in any tavern, but to live from our own provisions, cooking for ourselves, sleeping outdoors—briefly, to attempt an adventure.

In the Schlögener Schlinge (a narrow bend of the river below Passau), near the ruins of “Haibach,” we spent the night in a cave during a thunderstorm. A strong draft made itself unpleasantly felt in the cave, and so we jokingly called it the “Hotel of the Rheumatic Troglodyte.” Long we searched in vain for the wind-hole, but finally found it, and tried with a boat-hook to widen it to reach the outside. In clearing away rubble, we discovered a very old fragmented skeleton, with the remains of a child’s ribcage lying upon the chest.

We gathered these surely centuries-old bones, buried them before the cave, fired three honor volleys from our revolvers over the grave, and built a “stone man” (a small pyramid of stones) above it. This find of a woman evidently buried alive with her child gave the first inspiration for the present poem.

On the Peoples Named

The Harlungen or Hegelingen (Latin Heruli) lived on the upper Danube. As late as the reign of Louis the Pious, a charter of 831 still mentions the ruined “Harlungoburg” in the “Harlungofeld” on the Erlauf, where today lies the village of Harlanden.

Within this Harlung territory lay the Roman town of Arelate, today’s Stadt-Pöchlarn on the right bank of the Danube. Opposite it, on the left bank, lay the Germanic vicus (settlement/market), still called Alt- or Groß-Pöchlarn, which forms its own market-town. This left-bank Pöchlarn is the Bechelaren of Ruodegar, although the Nibelungenlied wrongly gives the right-bank Pöchlarn this role.

All Germanic royal or ducal seats on the Danube lay on the left bank, opposite the Roman towns on the right—thus explaining the “twin towns” along the river, e.g. Passau–Ingolstadt–Ilzstadt; Urfahr–Linz; Stadt-Pöchlarn–Markt-Pöchlarn; Mautern–Krems; Komorn–Szoni; Pest–Ofen, etc.

Downriver from the Harlungen were the Rugians, with their royal seat at Chremisa (Krems), opposite the Roman Favianis (formerly Epurerburch, i.e. Ebersberg, today Mautern). Further east lay the Goths with their seat at Vindomina. North of the Goths, Rugians, and Harlungen dwelt the Marchmen and Quadi in the “land of horses” (Mährenland), which then also included the “horse-field” (Mährenfeld), today’s Marchfeld with the March River.

The chief town of Moravia was Ptolemy’s Eburodunum, German Eburodun (“Ebersburg”), from which the name gradually became “Burodun,” “Bur’dun,” “Bur’un,” “B’r’un,” and finally Brünn (Brno). Burodun’s Castle is today’s Spielberg above Brno.

These small kingdoms of the Harlungen, Rugians, Türkilinger, etc. (with the exception of the Gothic realm) were undoubtedly dependent on the powerful Moravian/Marchman kingdom. This is likely why Ruodegar bears the title “Margrave of Bechelaren” both in the Vilcina Saga and the Nibelungenlied, even though he was the head of the Heruli and thus properly their king.

So may this song of German womanly loyalty resound through the lands of Germania, in praise of the German woman—who has always preserved, and will preserve, the dignity of the high priestess, despite all the fleeting profanations of a present age hostile to all ideals.

Guido von List