Germanien 1933 Issue 5

The Fire Wheels of Lügde

By Rector R. Wehyan, Frankfurt a. M.

Occasionally, during the Pentecost meeting of the Friends of Germanic Prehistory, the participants take an excursion to Pyrmont and also visit the nearby town of Lügde, the "villa Lichidi" in ancient Westphalia. This town, already mentioned during the time of Charlemagne, still presents a medieval image with its walls, town gate, towers, and church. But it is also due to a tradition reaching back to the pagan past, especially the fire wheel ceremony, that this town receives visitors every year.

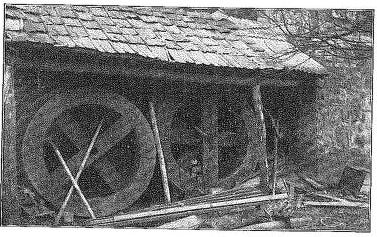

On the first Pentecost evening, a young man from the town prepares the fire or straw wheel, as shown in illustration 1, and brings it to the Osterberg for the procession. The town’s surroundings, particularly the Osterberg hill, serve as the stage for the fire wheel event. The participants climb the hill, and the onlookers gather at the bottom, eager to witness whether the wheel, once lit, will remain intact as it rolls down to the valley.

The process is ancient: on "Silent Friday" the participants collect straw and wood for the preparation of the wheels. Once they are made, they are moved as close to the fire site as possible. The straw is firmly packed into the wooden wheel, secured with rope, and made ready for the fire.

The exciting moment arrives when, just after dusk, the wheel is ignited and begins its journey down the hill. If it reaches the bottom without falling apart, it is seen as a favorable omen for the harvest. The responsible participants guide the wheel and ensure its safe rolling down the Osterberg.

This custom, unique in the region, carries significant local pride. The fire wheel tradition continues to evoke excitement and attracts the attention of both locals and visitors. Though rooted in pre-Christian traditions, the event is a symbol of Lügde’s cultural identity and enduring spirit.

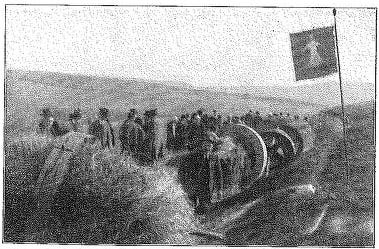

After these preparations on the Osterberg, the “Dechen” (assumed to be local villagers or participants) descend into the valley, where a communal meal is taken. However, two or perhaps more remain behind to guard the wheels, ensuring that the straw is not prematurely set alight by some mischievous hand. In the valley, a large pile of brushwood is set up, which will be lit in the evening as soon as the actual procession of the wheels is completed. Naturally, at the foot of the hill, on the riverbank where the valley stretches, many people are already gathering to watch the spectacle. There is no lack of joviality here, as the people enjoy their refreshments. When the burning is about to begin, a choir sings the following chorus:

"This is the high Osterberg,

Upon it the Dechen dwell,

In the evening, when the sun has set,

The wheels roll down

Triumph of ancient custom."

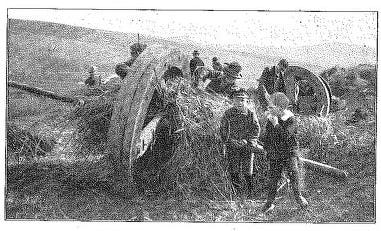

The oldest board member of the Dechen now lights the brushwood pile, upon which a fire also flares up on the mountain. A shot is fired, and this is the sign that the first wheel is to begin its fire ride into the valley. One of the Dechen, who remained on the mountain, takes a small bundle of straw, ignites it at the fire, quickly runs to the first wheel, and sets the straw on it ablaze. Immediately, the wheel bursts into flames. A push with a long fork sets it in motion, and like a fiery roller, it first rolls slowly, then increasingly faster, down the slope, trailing blazing flames of straw behind it.

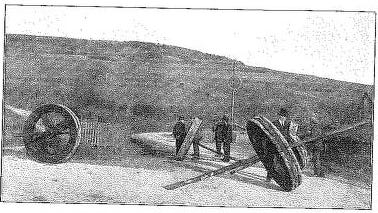

The irregularities of the mountain slope are easily overcome by the wheel; it jumps over ditches and slopes, here and there receiving a little help. So that the wheel does not topple over, a rod that protrudes about three meters from one side of the wheel is used as a stabilizer. Under the loud cheers of the crowd, the wheel reaches the valley. Here it is awaited by the Dechen, who are armed with water buckets, with which they extinguish the wheel as soon as it reaches the bottom.

It is said that when the wheel is extinguished too late, the harvest will be less bountiful; when a wheel reaches a large brushwood pile without being extinguished, which has happened in previous years, the resulting fire can spread greatly.

As soon as the first wheel has completed its journey and fulfilled its duty, the second one follows, until all six wheels have arrived in the valley. Then the Dechen return to the mountain to bring their fiery wheels into the valley. Afterward, with this spectacle in their minds, the crowd returns to the town, where the more pleasurable part of the custom begins.

How old the sensible custom here in Lügde is, can no longer be determined; however, it is assumed that it reaches far back into prehistory. We are justified in this assumption because the custom of firewheels has also been preserved in many other regions of Germany. The Brothers Grimm, for example, report a similar custom in the Moselle villages of Konz, where the firewheels, however, are not burned on an open field but are instead rolled down St. John's Day. The men of Konz climb the nearby hill on St. John's Eve and wrap a mighty wheel with straw, which is then delivered by the community. A pole is inserted through the wheel and held at both ends by two men. The citizenry gives a sign to the bearers of the pole, who then set the wheel in motion. The men accompany the firewheel down, following it with the hope that it will reach the water of the Moselle, for if it does, a good vintage is expected.

Other places where the firewheels are practiced include Ramersdorf, Beuel, and Küdinghoven (near Oberkassel) in Rhineland, in Carinthia. This custom of pushing firewheels down a mountain has also been maintained by the Grafschaft, whose sides and slopes are not to be overlooked.

Today, a similar custom is also observed with a "tarter barrel," which is rolled down a hill. The empty tar barrel, which still contains plenty of tar at its inner walls and bottom, is filled with straw, ignited, and rolled down in a similar manner to the wheels. Mannhardt reports from Schleswig. However, besides these, no further such customs have been noted.

Perhaps we should remember that as boys, we used to enjoy making offerings on such fires. If we could get hold of an old tar barrel, we would fill it with straw and pitch, ignite it, and roll it down the hill in the same way as the big boys did with the real firewheels. Also, we added as much wood to it as possible, placed woodchips and chips into it to our hearts’ content. Sometimes, people would argue whether a firewheel should be used or not, but despite such disputes, the fire customs were kept alive.

These firewheels are lit and burned today not only at Easter fires but also at other important natural dates, like when corn should be harvested or even at the autumn harvest, or when sacrifices to water were once made. People used to fear evil spirits, and these fires drove them away.

Finally, it should be noted that fire customs in these regions are not limited to open fires (whether lit at Easter or on St. John's Day).

The wheels, discs, hoops, and other objects, including the tar barrels that have somewhat taken their place, are obviously symbols of the sun, which rises again in the spring on its arch, bringing summer.

Symbolic Elements in the Image of Elstertrebnitz

By Dr. H. O. Plassmann

A coincidence occurred when, in the February issue of this journal (alongside my statement "Coincidental and Symbolic"), Wilhelm Teudt's work "The Heidenstein of Arnau" once again brought up the image of Elftertrebnit as an example of Germanic-Christian religious convergence. This coincidence prompted me to thoroughly compare the formal structure of the mentioned image with the sequence of forms I presented in my work. What is strikingly surprising is that we find almost the entire formal structure of that sequence on the image of Elftertrebnit, the fullest expression of which can be seen in the images on the baptismal font of Selde (see "Germania" 1933, 2.6.39).

It would hardly be appropriate to speak of mere coincidence here. What is truly astonishing is the realization that we are, in a sense, only just learning to see our own early monuments in their full symbolic meaning. Furthermore, the fact that the image-poor Germanic art, which traditionally showed an aversion to the portrayal of religious thinking, gradually reveals to us a pictorial language that allows us to peer into the origins of higher religious thought better than corrupted and distorted myths. This is a new perspective in the history of religion, which Teudt undoubtedly sensed correctly. For indeed, we must fundamentally revise our understanding of that intellectual process called "instruction," when we recognize that the new religion not only — as has long been known — connected to the external practices of old beliefs but also utilized the symbolic forms of the preceding faith to make itself comprehensible to the former adherents of that faith. This is far more than a superficial adoption of vanishing forms; it is an internal grasp of the creative thought that lived in the religion being surpassed or to be surpassed. Thus, it is the exact opposite of the "eradication" that a more blind era believed to be the precondition for "instruction." It represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the "anima naturaliter christiana" (the naturally Christian soul), as spoken of by an enlightened Church Father, even in the case of the Germanic "pagans."

These conclusions arise, at least when a significant portion of the formal structure of this undoubtedly Christian image can be shown to be northern and thus Germanic. This formal structure, however, is so numerous and meaningful here that no doubt seems possible to me. Let us first consider the "throne" on which God the Father or Christ appears: a structure of five steps, with a rectangular stone at the top, the front of which has a semicircular space carved out. Except for the number of steps, this "throne" corresponds exactly to the rock tomb uncovered last year at the foot of the Externsteine (illustration in issue 3 of this journal, 1932). While the Elftertrebnit image shows a proper stepped pyramid seemingly accessible from all sides, the "rock tomb" has only two steps at the front, yet it is also marked by side steps as climbable.

This stepped pyramid plays an important role in Germanic law, whose religious origins are becoming ever clearer. It is known as the "stafflum regis" in Frankish law, the standing place of the ruling king. Even today, the "staffel stones" recall the old form of these judgment stones, which were usually crowned with a post ("stick and stone"). Originally, they were apparently marked as signs of divinity. The French "perron," the "broad stone," like the "stafflum," later took on the meaning of a stairway. The tiered stone pedestal, even if it later appears as a symbol of the godly peace introduced from the West, can be demonstrated as Germanic, or rather Old Norse.

The most striking similarity lies in the front side with the semicircular arch, which corresponds to the equally empty arch on the baptismal font at Selde. From the perspective of religious history, the entire motif seems to fall into the category of "empty thrones," which were symbolically regarded as seats of the invisible divinity. Schuchardt, in my opinion, rightly interprets menhirs throughout as "thrones of honor" (the phallic interpretation seems to me a much later, degenerate layer of thought). The post on the Germanic judicial stone, in particular, appears to me originally much more as a symbol of the invisible god than as a "pillar god" or "fetish"—terms that I believe were arbitrarily imposed on our scholarly worldview from the conceptual world of lower peoples. If the interpretation of this cultic post had been as primitive and idol-like, the post, which also appears as a cross (galgo), would not have been so easily transformed into the Christian cross; rather, it would have been removed by all possible means. Here too, we are dealing with a genuine adoption of a symbol from a related primordial concept—never, however, has the symbol of something intellectually or morally inferior become the symbol of something intellectually and morally immeasurably superior; we find spiritual degeneration throughout history, but nowhere do we find elevation of a moral and spiritual concept.

The throne with five steps can certainly also be traced back to an Iranian origin in this sense as an empty throne; it has long been preserved in the cult of Mani. "Every year, the memorial festival of the founder was celebrated, which was called 'Bema' after the empty, decorated chair symbolizing the invisible presence of Mani. The five steps of the chair represented the five degrees of the 'Father of Greatness.'" The world mountain with five steps appears as the "Olympos eschatos" as early as in Parmenides and Anaximenes. However, I do not believe that in our case, with the image of Elftertrebnit, the five-step throne of God is of Iranian origin, possibly mediated through Byzantium; the empty throne already appears on an old Christian gem as a symbol of the invisible divinity. "The stone shows, in very good workmanship, a throne in frontal view. On the seat of the throne lies a crown, in which the monogram of Christ, formed from I and X, is inscribed in a star shape." This monogram is the well-known rune "hagal" = X, which also in Norse symbolizes "God." In place of this crown, as a symbol of the invisible divinity, the post appears on the Germanic stepped pyramid. I also cannot see why, when we must compare our own religious treasures to those of other cultures, we should seek these comparisons specifically among the peoples of Africa and the South Seas, rather than among the closely related, highly developed Indo-Germans. Perhaps because a simple post is "more primitive" than a crown or a throne?

Let us therefore initially stay with this working hypothesis: the stepped pyramid is originally the empty throne of the divinity. One step further along the path toward representation, and the divinity itself appears on this throne—not, however, seated or standing or otherwise depicted in a naturalistic way, but in a thoroughly symbolic form, closer to the pure concept. This symbolic interpretation brings us back to the sequence of forms discussed in my previous article: it is a pictorial extension of the upward-stretched pair of arms, as seen in its purely abstract form on the baptismal font at Selde, and in a more naturalistic form in the Tübingen Connenstein. Here, one more step has been taken: the concentric solar circle has become a halo, in the center of which the face appears; the left hand holds the book with the Alpha and Omega (the arm is shortened as the elements collide), because the ideas must be unified; but the relationship of the image components to one another is undeniably the same, and it is hardly a coincidence that this combination of motifs, which on the two other stones represents the high summer, also appears here at the summit of the "world mountain."

I may cite a passage from mystical literature to show how these pictorially abstract ideas truly persisted and bore fruit in the imagination of the Middle Ages. In a vision, it says: "I saw a great mountain, which was high and wide and of unspeakably beautiful shape. Five paths led up the mountain, all leading to the noble mountain, to the highest seat that was there at the top. They rose higher and higher, so that the seat itself was the highest, and the highest being itself. And I was taken up and led to the mountain. There I saw a face in eternal bliss, in which all the paths ended, and in which all who completed the paths became one." It is "the true face, which sees and illuminates all . . . it was like a great fiery flood." This points to a solar meaning, for Helios, the sun, is the one who, according to the great Orphic hymn, "sees all and oversees all." From the rest of the content, it is clear that the five "paths," which "rose higher and higher," can only be five steps; the "fiery face" at the top of the stepped mountain can be nothing other than the solar disc, which is still recognizable in Selde and Tübingen, while in Elftertrebnit it truly appears as a "face" in the radiant halo.

The thematic correspondence continues: on the second panel of the stone from Selde, the developing "tree of life" appears, which reappears as the "Irminsul" at the Externsteine—a designation, however, that I cannot completely suppress some reservations about. This structure appears here in a form much closer to the abstract primordial shape, as the so-called "lily," which became most famous in the ornamental design of the French Oriflamme. It also shows here the form of the blooming tree, though the three "roots" are better discernible than in the other images. Thus, we have here again the formulaic sequence: blooming tree of life – raised pair of arms; may we assume that in the crucifix to the right of the throne, the sequence continues, and that the dying Christ thus represents the dying, descending year; that he descends from the wood of the cross into the "underworld"?

With so much meaningful agreement, we cannot attribute everything to coincidence. One more thing must be pointed out: the strange decoration on the breast of the figure of Christ-God. If the central line were extended upward, it would form the Christogram or the Hagal rune, which, as already mentioned, is the sign of the invisible God on the ancient Christian gem. In this case, the representation would consist of the divine image growing out of the divine sign; originally, as on the ancient Christian depiction, the sign alone may have been on the empty throne. Be that as it may: if we indeed find the cross of Christ integrated into a pre-Christian religious sequence of ideas, then this would confirm our assumption that the propagators of the Christian faith, who created this monument, had indeed made a profound adoption of a religious concept they found, to make their own ideas visible within it. Evolution, not revolution! It is hard to imagine what the image would have looked like if this approach had been applied universally. — As for the time period to which the Elftertrebnit stone belongs, I will leave that to the judgment of art historians; however, the stone from Selde also dates from the early 13th century, yet it almost purely reflects a body of thought that cannot be explained by Christian origin. That this body of thought was not suddenly uprooted is shown by the history of our mysticism, which continued to develop old forms of thought in religious intellectual life, as was also done by the art of stonemasons and carpenters in religious architecture.

Incidentally, the stepped pyramid also appears on early Nordic monuments, such as on an Irish harp from the 13th century in Trinity College, Dublin; it has three steps and bears an upright hand at the top, with the symbol Y above it, which we regard as the abstract primordial form of the hand. Here too, probably related to the high summer. The six-spoked wheel has practically become a symbol of godly peace, much like the "perron," with which it frequently appears together; such a "perron" as a stepped pyramid also appears on a Swedish gravestone. In any case, one cannot understand a religious attitude, whose basic principle is iconoclasm or rather symbolic representation, from the intellectual stance of the image-rich religions, and even less from that of primitive peoples who have remained in religious dullness. A fundamental rethinking is required, and that will always, in large part, be a matter of good will.

Nordic architecture in Bolivia?

By Edmund Kiss

Anyone who visits the prehistoric ruins in Bolivia and Peru will typically have the desire to explore Indian prehistory through their buildings and craftsmanship. There are plenty of opportunities to do so, and one can admire the architecture, which appears strange—strange to the traditional artistic taste in both structure and decoration. And for those who wander through the ruined cities with calipers, camera, and field book, they are often astonished by the gigantic architectural elements made of polished andesite, whose artistic treatment in terms of decoration and stonework does not at all align with the distinct characteristics of Indian art, which can, however, be compared in the nearby vicinity. As sketches and measurements fill page after page of the field book, a peculiar suspicion arises, a question that almost seems absurd: Is this Indian architecture?

The author of this article initially sought only Indian architecture in the prehistoric capital of Tihuanaku in Bolivia. However, what he found at an altitude of nearly 4000 meters above sea level was a masterfully developed, mature architecture that is by no means Indian.

What now awaits the researcher in historical terms on the Meseta of Bolivia, the highlands between both South American regions on the southern hemisphere of the Earth, are the powerful ruins of the ancient city of Tihuanaku, revealing an architecture that deserves the name "Hall" just as much as the so-called styles of historical periods. That this is not Indian architecture but something entirely different cannot be proven with words; here, the illustration and the architecture itself must speak.

Amidst the ruins of Tihuanaku lies a low, artificially elevated stepped structure, crowned by the remains of an old building, which the native Indians call Puma Punku, or roughly translated as "Water Gate." The designation seems to be correct, as the stepped structure is located directly next to two silted-up harbors that were in use in unknown ancient times, when Lake Titicaca had a larger expanse than it does today. The structure on the hill's platform is heavily decayed, but the ground plan is so well preserved due to the use of enormous stone blocks that it is possible to form a vivid image of the original building. The exterior construction is not primarily missing here, but rather the sculptural works, which lie in abundance in the form of heavy, well-preserved building blocks scattered around or protruding from the ground. Particularly noticeable are the numerous niches, which may have led some researchers to believe that the structure was a mortuary house, with the niches perhaps intended to hold urns or small deity figures.

It is relatively simple to assemble the existing building parts in such a way that, by considering the ground plan of the layout, an almost accurate image of the building's original state emerges. This is made easier by the fact that some stones are shaped on both sides, allowing the rear wall to be reconstructed at the same time. The author has undertaken this attempt and, using only available stones, has reconstructed the architecture of Puma Punku.

Fig. 1 shows part of the interior with niche rows, Fig. 2 the corresponding exterior. Fig. 1 depicts a niche wall, designed with such security and artistry in construction and proportions that many readers might agree with me in calling this building style "classical." The same applies to the exterior, which displays a row of crosses in raised work with outstanding shadow effects. Above it lies a main cornice, finely balanced in its proportions. It instinctively feels like an old acquaintance from classical architecture of historical Greek antiquity, and one inevitably wonders how such forms found their way into South America, into the land of the Indians. It seems the Greeks did not invent their beautiful cornice arrangements themselves, for there is no doubt that the builder of Tihuanaku had already been lying in his grave for several millennia before the sound of the Greek stonemasons’ hammers echoed on the Acropolis.

The main cornice of Puma Punku has once again been singled out as a model of its perfection in Fig. 3.

Figures 4 shows another interior of the mortuary house with niches, connected with the cross motif, which Figure 2 depicts on the outer wall in a slightly modified form. It is probably unnecessary to assure that these crosses have nothing to do with any Christian thought processes. The niche wall in Figure 4 itself provides the proof that words cannot convey: it is a classical architecture from which even we, people of our time, can still learn. The restoration of this wall was achieved primarily using a single block of stone, as can be easily determined by examining the joint cuts. Only the uppermost stone band was used arbitrarily, but it is likely that the upper closure was formed in this simple way. The hall enclosed by such walls had no roof. In Puma Punku’s mortuary house, there were also rooms covered with large andesite slabs. However, these covered rooms seem to have had no decorative walls inside, partly because the mausoleum had no windows.

In Puma Punku, there are two main cornices, which probably—at least one of them—belonged to neighboring mausoleums, of which there are several in the ruin field. The cornices are depicted in Figures 5 and 6. In Figure 5, the temptation was to restore it by adding an architrave beam so that the triglyph-like consoles would have a similar effect as in the Doric triglyph-metope cornices. There was no indication, however, that the builder of Tihuanaku assembled his cornice in the manner known to us. It can be assumed with high probability that the main cornice in Figure 5 looked as it is drawn. The restoration of Figure 6 was more certain. Here, only the existing proper cornice with the slab and the simple but very effective frieze were combined.

Only one window from Tihuanaku has been preserved; it is in the National Museum in La Paz, Bolivia. It is not known where in the walls of the numerous buildings of the ancient city of Tihuanaku such windows were used. It is likely that they were closed with thin, translucent alabaster slabs, unless they were left open due to the possibly better climate conditions in the past. Such approximately square-meter-sized alabaster slabs were apparently found on the ruin field of Tihuanaku at the time of the Spanish conquest, as one such slab today serves as a window cover in the chapel basement of the Christian church of the new town of Tihuanaku, dating from the late 16th century.

The shape of the window in Figure 7 shows the characteristic stepped form, also present in the niches, in its lower section. The lintel is closed by a parabolic arch. The free window space is divided by a simple but highly effective tracery, formed from two interlocking parabolas. The entire window, including the tracery, is carved from a single slab of andesite lava. Clearly, this sculptural work from prehistoric times presents an architectural mindset of great inner maturity, which has nothing in common with the spirit of Indian art, as that lacks inner clarity.

Figure 8 serves as an example of the artistic treatment of door openings. It represents the restoration of the west wall of the so-called Sun Gate in Tihuanaku from the interior of the solar observatory Kalasasaya; restoration in the sense that the side sections, barely indicated in Figure 8, are supplemented. The central piece with the gate, the large side niches, and the smaller niches of the upper row is carved from a single block of lava, and—even though heavily weathered—it is fully preserved. The top of the gate wall was completed by me with the slightly slanted slab, fragments of which are also present. It is not known, however, whether this slab originally crowned the gate in this form.

On the ruin field of Puma Punku, there are three other similar gates with side niches, also carved from a single block, and several similar gates lie scattered in other ruin sites of the ancient city.

The sight of the precisely and carefully executed architecture of the gate in Figure 8 will further reinforce the suspicion that such a work of art could not possibly have been created by the ancestors of the Indians. Indeed, anyone who carefully examines and reflects on the illustrations will come to the conclusion—without any particular mental effort—that a Nordic people, perhaps related in nature to the Greeks of antiquity, must have left their high art here. It is certainly incomprehensible how this could have occurred on the southern scale of the Earth, near the equator and at an altitude of almost 4,000 meters above sea level. And yet, this seems to have been the case, especially since the old Kalasasaya, the solar observatory of the prehistoric city, revealed a buried stone sculpture, deep in the gray clay of the former Lake Titicaca. A photograph of this sculpture is included in Figure 9. It is hardly necessary to say that this half-finished head is not the likeness of an Andean native.

Without delving into how such completed architecture could have reached the highlands of Bolivia: in the city of Tihuanaku, people of Nordic type with high culture must have lived, and the works of art in the prehistoric city are certainly not of Indian character and architecture, but very likely the work of Nordic men who once, as bearers of a particular culture, also came to the highlands between the Andes.

Germanic Astronomy

Gustav Hegel and the Germanic Sanctuaries

(Excerpt from Issue 4, p. 99)

By Wilhelm Teudt

The recognition of the findings at the Externsteine naturally raises the question of further signs of astronomical activity in the landscape around the Osning Mountains, especially regarding a place that shows indications that the necessary preconditions for the Externsteine phenomena could have been established there. The developments have reached the point where someone who has accepted the findings at the Externsteine can no longer overlook the facts that reveal the Ofterholz estate not only as a prehistoric settlement but also as an ancient sacred site—even if one initially ignores the question of astronomy. For me personally, the direct impression of the site and then the astronomical considerations preceded the historical and other reasons; but now my experiences must step back in favor of the logically correct sequence.

a) From an archaeological standpoint, the Ofterholz estate, with its surroundings, is identified as a site used from the Stone Age and the earliest Bronze Age, through the Roman period, and all periods of the Iron Age up to the present day.

b) Topographically and in terms of settlement history, the site possesses qualities that were demonstrably utilized by settlers of the Bronze Age and earlier (water supply, soil conditions, and location at the edge of a heath and a large forested hunting area).

c) Historically and archivally, there are rich records that necessarily refer to this very estate, going back to the time of Louis the Pious. These records show that from the beginning, it was a public estate, as the first known owner, Bevo, son of the Saxon Duke Egbert, an Anglo-Saxon, could only have received this piece of territory (directly or indirectly through his father) from the king. From the year 1002, the estate remained a fiefdom of the Paderborn Church until 1591. The Schwarzmeiershof, now Sternhof, is the only estate in question for the donation by Queen Oda in 1002, as only it was a Paderborn fief in Ofterholz, as confirmed by the oldest feudal document (1492), which states it was "always" so. The often-circulated objection that the estate is only a few hundred years old is a complete reversal of historical truth.

With high probability, the estate was the site of a monastery foundation (Sethi) between 815-822, which, in its details, strongly suggests that it must have once been a Germanic sacred site.

d) Of great importance for the cultic character of the Ofterholz estate is its location in the middle of a prominent landmark area, which demonstrates its cultic significance through the presence of other sacred sites (sacred groves, countless megalithic tombs, courts of law, "Hünenkirche" or "Giants' Church"). On the estate itself is a remarkable spring construction under an artificial mound, whose origin is unlikely to date from the Christian centuries.

As a historical document, the report from Wasserbach (circa 1690) of a "fanum Ostarae Deae prope Oesterholz" (sanctuary of the goddess Ostara near Oesterholz) is of great value. Additionally, there are various local legends and oral traditions that have persisted.

e) Linguistically and onomastically, the names that accumulate around Ofterholz, such as "Hünnenkirche" (Giants' Church), "Heidentor" (Heathens' Gate), "Debingerheide," "Gudenslau," and the names of the enclosed groves like "Königslau," "Langelau," and "Edelau," must not be overlooked by anyone who wishes to let the unique characteristics of the Ofterholz landscape influence their judgment on the questions connected to the estate.

f) The estate has a peculiar fortress-like enclosure, consisting partly of walls with ramparts, and partly of walls alone. This construction appears puzzling to both agricultural and military experts because neither military considerations at any time nor agricultural needs or other criteria justify the estate's size, layout, or design.

This is not an ordinary estate but an archaeologically significant object in a most striking environment, to which the peculiar astronomical findings are an additional plus. If such an object has so far escaped the attention of researchers, the reasons are obvious: the neglect of a thousand years cannot be rectified in a few decades, and the focus of our archaeologists on soil finds has not yet allowed for sufficient attention to the historical evidence visible in the landscape.

g) The astronomical findings, as documented in the report, stand firm; no astronomer or anyone else has disputed the fact that the natural features and lines of the estate's enclosure, as depicted in the cadastral extract, exhibit the claimed astronomical properties. The objections raised by opponents merely concern the extent to which the presented facts should be considered as evidence. Even if, for example, one were to give more weight to the longer (disturbed) section of line I rather than the shorter (undisturbed) section, or if other stellar positions were considered, or if similar astronomical meanings could be found in many comparable places—which is all still to be contested—this would in no way change the fact that the astronomical study of the estate's enclosure yields the specific findings in question. These findings, whose purely astronomical quality could rarely arise by chance (the number can be determined through the most modest arithmetic to be at least 30 to 60), far surpass all other comparative attempts at other locations, and their inner mythological and cultic value can hardly be theoretically surpassed.

If planets cannot be considered here, if the midday line of the sun and the northern extreme line of the moon must be recognized as cultic lines of the highest rank, and if, as we shall now see, the selection of the Ofterholz azimuths presents us with an astonishing picture, then this accomplishment reflects an extraordinary consistency in the possible understanding of the task before us.

The fact that we are dealing here—as with the astronomical conclusions drawn by the expert reports—with matters subject to subjective judgment is the same situation faced by anyone engaging with history, especially prehistory. The star azimuths are measurable and countable, but the conclusions drawn from them by the experts are subject to personal interpretation. Anyone unable or unwilling to spend time and effort delving into astronomical concepts has no choice but either to abstain or to submit to the authority of one or another astronomer. Neugebauer, a leading specialist in astronomical chronology, disproved the objection that the time calculation for the Ofterholz phenomena was insufficiently clear by conducting comprehensive calculations of all relevant bright stars (Mannus XX, 1-3, p. 222). His conclusion, that the only period between -4000 and 1800 (Goethe’s time) during which a suitable constellation of bright stars for Ofterholz could have occurred was around -1850, is, in my opinion, of overwhelming significance. It is a special stroke of fortune that such striking constellations like the one at Ofterholz did not occur more frequently, even though they could theoretically have been possible. Had they occurred more often, the evidential strength of the Ofterholz phenomena would have been diminished in the same measure; but they simply did not occur. Medel's cautious stance towards the astronomical elements of my book, particularly regarding Ofterholz, is primarily based on his view that the correspondences I drew from Oriental astral mythology are unprovable or unacceptable. He assumes that a mythological significance of the Ofterholz stars is an indispensable foundation of the Ofterholz case, and its absence would lead to the collapse of the thesis. This, however, is not the case. This is evident from the fact that, as presented in the first edition of my book, the Berlin astronomer and I merely pointed out the noteworthy fact that the same stars seen at Ofterholz play the primary role in Oriental astral mythology. Surely that is permissible? Only in the second edition did I then add further, as a valuable confirmation, that all four stars significant within a "fanum Ostarae Deae prope Oesterholz" were associated with the attributes of the female deity in the Orient—namely a goddess whose name Ishtar or Astarte shows a plausible connection to the name Ostara. It cannot be required that, due to ongoing differences of opinion on this matter, I should refrain from pointing out such a coincidence, to which, if necessary, the highest evidential value must be ascribed.

However, the foundation of our Ofterholz thesis stands independently of such Oriental correspondences, indeed independent of any mythological interpretation, well-supported by the facts that are found here in Germania.

These facts consist in the selection of stars at Ofterholz, even purely from an astronomical perspective, representing a fine selection: Sirius, Capella, Orion, and Gemini. According to Neugebauer (Mannus XX, 1, p. 222), there are only 16 non-polar, bright stars; four to six of them are excluded because they belong to already counted constellations. The exclusion of stars such as Praesepe and Fomalhaut, scarcely mentioned in otherwise verbose Oriental astronomy, is unlikely to provoke much objection. Thus, aside from the sun and moon, only eight to ten stars remain relevant. The fact that in the 58 time periods (each 100 years) since -4000, there has only been one period—around -1850 (and not again until around -1800)—in which the horizon position of four of these eight to ten stars aligned with Ofterholz azimuths, and that furthermore the 5th azimuth aligns with a significant moon line, and the 6th azimuth marks the meridian, represents an undeniable fact. This fact, even without proof of mythological significance, makes an explanation by chance seem a bold assumption.

Even if one does not believe in a linguistic or conceptual connection between Ostara and Ishtar (perhaps a remnant of once-shared primal conceptions of peoples), even if the goat Heidrun has nothing to do with the Capella star, and even if Freya’s spindle is to be separated from Orion’s belt stars—then the astronomical foundations of the Ofterholz case remain unaffected. However, some acceptable and plausible explanations would fall away.

If I believe, therefore, that such peripheral elements playing a minor role should not be overly emphasized, let alone lead to disbelief, Medel's concluding remarks on the astronomical question still reveal that, even for him, the Germanic astronomy derived from my observations is far from being dismissed. He writes: "This rejection does not mean that the outrage and scorn with which Teudt has been showered is justified. The observations at the Sazellum of the Externsteine, and similarly those presented by Teudt in several places regarding 'sacred lines' and similar matters, provoke thought in anyone who considers the question thoughtfully and without prejudice."

We saw that the doubts regarding the justification of explaining Germanic matters through Oriental elements play no decisive role in the assessment of my astronomical findings. However, I neither intend to diminish the great importance of this question in itself nor—should the doubts be dispelled by scientific progress—reduce its very high value, especially for the Ofterholz thesis.

In my view, the research results of archaeology and comparative studies in religion, mythology, symbolism, and linguistics have so far tended to move more in the direction of a positive answer to this question than a negative one.

If the cultural connections between Germania and the Orient, claimed by recent archaeology (Schuchardt and Rosinna) for the 3rd millennium BC, are accurate, then there is no reason to deny spiritual-cultural connections during the Bronze Age. And if the plausibly argued unity of certain religious, mythological, and cultic ideas among peoples from their earliest times (Herman Wirth!) must also be considered, then the value of seemingly uncertain Oriental correspondences rises to the level of "evidence" (with a grain of salt) for Germanic astronomy.

Taking Medel's critique and suggestions into account, I will, in future treatments of the astronomical question, only incorporate the Oriental correspondences and linguistic aspects in a way that avoids overemphasis, and the Externsteine facts will be more strongly highlighted as the core of the other astronomical arguments. In doing so, the different levels of the hypothetical nature of a case, on the one hand, and the facts that appear to me as proven, on the other, will become even more clearly distinguished.

***

When Medel's critique takes up as much space concerning the part of my book related to Germanic astronomy as it does for the rest of the content, there is a clear reason for this. For the proof of an already advanced astronomical science on Germanic soil during the Bronze Age undoubtedly presents a very compelling argument for the high level of ancient indigenous intellectual culture. It is necessary for this to be thoroughly examined in all directions. It is worth fighting for this stronghold, and so my defense against the objections had to take up a broad scope. Nonetheless, I must point out that the astronomical aspect forms only a fraction of the content of my book, and the rest concerns Germanic sanctuaries and cultural questions, which, I believe, are also of considerable importance for understanding the Germanic past of our people. I especially mention the insights provided by the sacred groves of the Leistrup forest and the Ofterholz district.

Medel agrees with some points, questions others, and rejects yet others. That, as Medel expresses it, some concessions may appear "trivial" to some is possible; nevertheless, it would not be difficult for me to demonstrate that they are capable of fundamentally transforming common understandings of important cultural issues. Medel himself mentions stone and lime mortar construction and adds a valuable contribution—the ancient word "Leim" with its meaning "mortar."

Medel, as a linguist, took little pleasure in my linguistic interpretation proposals. These have brought me much opposition, but also agreement and much stimulation. In this area, I am more than willing to accept correction, as my rather sparse interpretations of place names can often be dispensed with without significant harm.

Medel’s approval of Schuchhardt’s identification of the Grotenburg with the Teutoburg, which I believe I have illuminated strongly, is immensely valuable.

I cannot claim that I consider all "folk traditions as ancient and indigenous." If I perhaps did not emphasize sufficiently that it should remain undecided to what extent the traditions may be regarded as ancient and indigenous, I have considered such a limitation as self-evident. In this field, as in many others, it must be left to the historical sensibility of each individual reader to decide the value they ascribe to tradition, legend, or hearsay. In doing so, the factual elements often contained in the legend (e.g., in the devil's legend of the Externsteine), or the moments explainable only from a specific cultural environment (e.g., the cattle sacrifices in the Rohlstädter Hünenkirche), or the concentration of traditions at a particular location (e.g., the Ofterholz estate), will naturally play a role.

Regarding the Edda question, I will limit myself to quoting what Medel writes to me: "If one declares the Eddic material as distorted a priori, one renounces any deeper insight into Germanic mythology. It is by no means certain that it was 'the hands of priests' that recorded the pagan traditions from Iceland. Sacred and secular matters can be clearly distinguished almost throughout the Icelandic manuscripts, and the gods' stories are divided into priestly fables and genuine myths. The content of Snorri's Edda (Thule, Vol. 20) consists largely of myths, as do the Edda poems (Thule, Vols. 1 and 2). Priestly fables, in which the gods appear as devils or unclean spirits, are found in the sagas of kings (Thule, Vols. 14–16), especially in the great collection of the Flateyjarbók. This is precisely the advantage of ancient Iceland over all other West Germanic regions: it shows both the distorted and the genuine side by side, with the latter in superior and richer abundance."

Regarding Arel Olrik's book in Danish and the materials he provided on the Irminsul question, I cannot yet comment. As for my historical assertions about the destruction of an Irminsul at the Externsteine by Charlemagne in 772, they stand entirely independent of North Germanic and Lappish accounts.

In conclusion, I repeat my expression of satisfaction with Medel’s fundamental agreement with my exploration into the obscurities of the Germanic past, and I hope that after further research and discussions, only a small, insignificant residue of the more important differences of opinion will remain. Then, as a result of Medel's response, we will not only see a clear path forward, but also a significant progress in the exploration of Germanic cultural life from the remnants found in our landscape.

"We must freely admit: the spiritual writers of the Middle Ages have misled us with their monastic mindset and falsified our history. We must adopt another belief in order to reclaim the place for our ancestors that rightfully belongs to them in the annals of the world." – Johann Clement von Amrum, 1836.

"Our past determines our fate from within, and the more familiar we become with it, the more familiar we will become with ourselves." – Moeller van den Brud.

Treasures of the Soil

Names in the Folklore of the Lausitz. A report about a peculiar folk belief is found in the very rare book: *Pison. The First Part. Of Cold, Warm, Mineral, and Metallic Waters, Together with the Comparison of Plants and Earthly Growths,* ten books by Leonhart Thurneisser zum Thurn, Frankfurt an der Oder, by Joh. Eichhorn, 1572. Folio. – On pages 357-359, the town of "Lüben in Lower Lausitz" is discussed; it states:

"There is in this area, not far from the town of Lüben, a wondrous kind of pots ('Haefen' - 'pots,' only in Upper German and part of the Central German dialects), which (as people say) are said to grow in this form by themselves. The story goes as follows: Around the time of Pentecost, especially during the Pentecost holidays, the country people go with sticks or spades to this area, and when they dig into the ground about an elbow's depth, they feel where the pots are. Usually, large stones are lying on top of them, and they dig around the pot with shovels and spades. (For the pots are soft, as if they had just been made by a potter, but not damp.) Once the pot has been dug up, they leave it to stand for a short time, after which it hardens. However, if they touch it before it hardens, it disintegrates like dust.

They tell me that in winter, fall, and spring, these pots lie about 20 feet deep in the earth, but around Pentecost, they are found only an elbow's depth below. It is a marvelous matter, as one finds not only pots of various forms but also pitchers, bowls, cups—large and small—of many kinds, as if one should carry them to market. What's even more wondrous is that sometimes brass rings, lead, and other materials are found with them, and occasionally even inside them. There are various opinions about this: some believe that they grow in this manner, which cannot be the case because nature does not replicate things so precisely. These pots are made so skillfully, round, and even that one can see little marks all around them, as if they were made on a potter's wheel. Moreover, they have handles, and some are broken, just as potters or pot-makers have the habit of pulling their work, which is why they cannot grow by themselves. If they grew, they would only come in one form, and they wouldn’t be so finely crafted. Also, they would not disappear, because in winter they are found very deep, while in summer, they lie very close to the surface, which likely has a natural cause, possibly due to the sun, which around Pentecost, when it is near us and in the sign of Gemini, is very strong. In winter, however, when it is farther from us and in the sign of Capricorn, it is weak. Moreover, they are found only in one location. As I have been informed, it is a large area where they are found, and one might occasionally find a mix of other materials in them, for nature can err at times, just as it does with fruit or even humans.

Therefore, these cannot be a natural growth, as they are so precisely and deliberately formed, as if ready for sale at the market. They are also not made by human hands, for if they had been fired, they would not become soft again. If they softened due to age, they would not harden again so quickly, but these do so within a short time after being found. At that point, they can be used for all kinds of purposes (for which vessels are usually needed). Thus, they remain at the spot where they were placed by people and do not rise or sink over time, which happens in other cases. Therefore, this must be something beyond the common course of nature. As a result, the Lausitz and Lusatian farmers have a saying that these pots are prepared by dwarfs who live in secret caves and place them there. While no one can show definitive proof of this or claim to have seen such dwarfs alive, there are some indications that bones of such small people have been found there. The most credible account involves a complete body that was only two feet three inches long, though only the bones remained, including the skull, which many trustworthy people have seen. While I could say much more on this, it is not the place here.

Nevertheless, these pots, whether they come from where they may, are certain to be found in Poland, near Rodaw and Paludy, as well as between the rivers Bóbr and Meuse, not far from Guben and Lobersberg, though they are said to be of a different kind. Returning to my point, it is certain that the first shards of these pots, when ground into powder, are among the best remedies for drying up moist wounds, especially for healing joint water that begins to ooze from wounds. Similar pots or vessels are also found at the Güldersberg, located half a mile from Sagan in the Via region, between Bergsforst and Greys, as well as near Trybel on the Bodholkerberg."

The fact that burial urns are seen as something uncanny is also reported from other regions of Germany; one need only think of the "Nulkenpötte" in Westphalia (see P. Jaunert, Westfälische Sagen, Jena 1927).

**Paleolithic Finds from East Thuringia**

So far, tools from the older Stone Age have mainly been discovered in caves, under overhanging rock shelters (French *abri sous roche*), or at sites where they were found alongside bones of Ice Age animals. In East Thuringia, Paleolithic cave settlements are known from the famous Lindenthal Hyena Cave in Gera, the "Wüsten Scheune" in the Orlagau between Neustadt and Pößneck, the newly excavated "Anie Cave" near Pößneck, the Hertha Cave near Ranis, the Fuchsloch on the Rote Berg near Saalfeld, the Rapfenberg near Pahren, and the Bat Cave near Ranis. The Stone Age cultures discovered at these various sites range from the simple Mousterian stage to the Magdalenian stage.

In addition to these settlements from the early Stone Age, the Paleolithic, open-air settlements have also been identified in recent years, which only recently started receiving attention.

In the Saale River region, or in the karst-affected Orlagau and the rugged nearby East Thuringian Slate Mountains, the Paleolithic human found sufficient shelter in caves, rock fissures, and under rock ledges, while in the northern foreland, open-air settlements predominate.

The northernmost open-air settlement of East Thuringia is located at the Schneidemühle near Breitenbach, close to Jena. It belongs to the Aurignacian stage and provided bones, some of which were burned, from mammoth, horse, deer, and wolf. The tools included blade scrapers, blades, and sickles. Further open-air settlements were recently excavated near Silmitz, not far from Kahla, and near Saaletal in the middle Saale Valley, which belong to the Magdalenian period. In the middle Elster Valley near Tan Berndorf, south of Gera, two clustered settlements and workstations of Magdalenian humans were found on the commanding Bockberg. They left behind their characteristic stone tools in various stages of processing.

Less attention was given to the deposits of gravel and sand from the time of the main glaciation and the subsequent interglacial period (Second Interglacial), which are found in East Thuringia, particularly in the northern part, covered by sandy clay and overlying loess. These are deposits from the second northern glaciation, the only one that reached East Thuringia up to the edge of the Slate Mountains. The most prominent traces are found in Windischendorf, Beutelsberg, and Meucha. Bruno Brause, a researcher in Gera, has dedicated the last ten years to studying these glacial gravel and sand deposits for Paleolithic stone tools. He succeeded in making Paleolithic finds at two locations near Gera, at Roschütz and Smirchau, which currently represent the oldest tools in eastern Thuringia. Most of the tools, struck from chert, include scrapers, knife-like tools, and sickles, with the exception of a quartzite hand axe from Smirchau near Ronneburg.

At Smirchau, along with the artifacts, pieces of charred wood and a fragment of a mammoth ivory wheel, along with bones, were found. The sand and gravel exposed by quarrying represent fluvial diluvium. The alternating layers of sand and gravel were formed by the retreating and advancing ice margin, which deposited the gravel or whose meltwater washed and redeposited the freshly deposited layers. The early Ice Age humans of the Mousterian stage must have lived as hunters near the ice margin in open-air stations, as the tool deposits between these earliest glacial layers cannot be explained otherwise.

On a disturbed interglacial terrace in the Elster Valley near Caaschwitz, north of Gera, the author found a site of stone tools (Mart Zick, No. 144, 1932) in a mixed diluvium beneath very thick sandy clay and loess. This site reveals a new open-air settlement from the primitive Mousterian stage. The humans must have followed the retreating northern ice margin of the second northern inland glaciation as hunters, settling for a longer time in this open-air settlement in the already deepened Elster Valley.

These new finds of Paleolithic tools supplement our knowledge of the Ice Age humans in Central Germany.

Rudolf Hundt.

-

Regarding Question 2 (Issue 1), Gymnasium teacher Werner-Detmold reports: "The name (mentioned by Jellinghaus in Lügde) is found on the Overbeck map of Lippe. G.A.B. Schierenberg had seen it and placed an Irminsul at that location without investigating the origin of the name. Prof. Dr. Meerth(t) determined that a member of the von Exterde family had been killed between Elbrinxen and Lügde." He asked Mr. W. to check if there might be a memorial stone in that area. Mr. W. found such a stone on the old road to Lügde. "Whether it still stands there, I do not know. The current road runs along the base of the mountain, where it joins the road from Harzberg. The old road leads steeply over the mountain from the last house on the road from Elbrinxen."

Regarding the same question, the following letter has also been received: It seems, after all, that the old claim that the name "Externsteine" means "Easter Stones" is gaining weight. Whether the Low German name for Easter—"Exter" or "Höxter"—is connected to the word agister or not, it is certain that there are "Easter Stones." Such stones include the "Heister-Steine" in the Seeblänken forest north of my residence in Waren in Mecklenburg. These are erratic boulders, only rising a few decimeters above the forest floor on undulating terrain, and they are considered to be megalithic burial stones. Heister or Heester, like Exter or Höxter, is the same as "Elster" (magpie). And the black and white magpie is called the "bird of death" in Hel in Weber's Dreizehnlinden. Before I even knew this, it occurred to me, as a layperson, that the strikingly black-and-white bird must have been a cult bird associated with the solstices and solstice sanctuaries. Professor Dr. Herman Wirth, to whom I recently posed a question about this, seemed to agree with me and was able to provide me with some important information on the "Easter question." It is clear that the qualities of the bird as the "bird of death" in Hel and as a solstice symbol do not exclude each other but fit well together: both the "son of God" and man "enter the earth at the winter solstice, die, and are reborn from it" (H. Wirth in Issue 1, 1933, p. 11).

Graves were also places of worship, and vice versa! Solstice sanctuaries, like the one near Horn, were therefore, like every megalithic tomb, "Easter Stones," although they likely had other, even more sacred names before and beyond this name. It may have been the intent of those who suppressed the sanctuaries of our ancestors, or perhaps even the intention of our persecuted forebears themselves, that the "harmless" name of "Easter-, Exter-, Heester-, or Heisterstones" displaced other more dangerous or sacred names of those sites.

To avoid the distracting association with the Latin "externus" ("external") for those familiar with Latin, it would be helpful if all friends of Germanic prehistory, both within and outside of our circle, would support the spelling "Exter-Steine" to gain prominence, as is practiced on the back of the image referenced in Question 2, which shows the yet-to-be-localized "Exter-Steine" of Mr. Wehmann.

Dr. med. Brenke.

The Book Scale

Ernst Tabeling, WaterLarum, Regarding the Religion of the Lares. Klostermann Verlag, Frankfurt a. M., 1932, 104 pages, 8°, 6.-

Tabeling's work appeared as the first volume of the Frankfurter Studien zur Religion und Kultur der Antike, edited by W. F. Otto, which—according to the editor’s announcement—aims to "lay the groundwork for a new comprehensive view of Greek and Roman antiquity." The initial focus is on ancient Roman religion, which serves as the primary subject of investigation. The discoveries made in recent years in Italy, along with the objections increasingly raised against certain fundamental assumptions of the Mommsen school (emphasized by me, D. H.), urgently call for a new examination of Roman tradition, whose results will continue to reflect the appreciation we owe that school, even in contemporary terms.

One might notice the absence of the name Bachofen in this announcement. However, the fundamental ideas of Bachofen, the great opponent of Mommsen, whose works classical philology is only now beginning to engage with—after Ludwig Klages first pointed out their significance—are clearly represented here. For example, the attempt is made to use Roman myths to explain Roman religion, just as Bachofen did, whereas the Mommsen school refused to recognize the value of Roman mythology. These studies from the Frankfurt seminar will hopefully also prepare the long-overdue confrontation between classical philology and Bachofen's individual assertions. However, we believe that this confrontation with Bachofen, like the foundation of a new comprehensive view of antiquity, can only succeed if classical philology acknowledges that a comprehensive understanding of Roman and Greek antiquity necessarily involves a comparison with ancient Germania. "These European South-Indo-Germans (Italics and Greeks) are nothing more... than the descendants of ancestors of the Brennus-era, the Infubres, Cimbri, Goths, and Lombards" (Medel). It is only the prejudices inherited from theology by humanism that still prevent classical philology from applying this new perspective, which alone guarantees an organic understanding. The exceedingly close kinship between the Italics and the Germanic peoples is becoming ever clearer. This, in turn, makes it the duty of Germanic studies to pay the utmost attention to the new research on ancient Roman religion.

With that, we return to the study at hand. Tabeling seeks to contribute by clarifying the nature of the "Mother of the Lares" as a preliminary step toward resolving the debated meaning of the Lares themselves. Several theories currently coexist in modern research. According to Tabeling’s findings, it can be considered settled that the view of Wissowa, who saw the Lares merely as "divine field guardians," must be definitively abandoned. What remains are the views of Samter, who considered the Lares to be ancestral spirits, and Otto, who regarded them as earth deities, emphasizing their generative nature. Tabeling’s investigation seems to point toward a synthesis of these two views as the final resolution of the Lares problem.

In a careful and thoroughly convincing manner, Tabeling demonstrates that the "Mother of the Lares" Mania—who was also called Lara, Larunda, Dea Tacita, and Dea Muta, and in earlier times Acca Larentia, meaning "the mother belonging to the Lares"—was originally both a life-giving and death-bringing deity, identical to Genita Mana, i.e., Mother Earth, who gives birth to all life and reclaims it into her womb. This understanding, which was already found in Bachofen’s 1870 study Die Sage von Lanaquil, where Larentia is described as "Mother of Life and Death," has now been reestablished and affirmed on all sides.

The main festival of the Lares is the Larentalia, an ancient festival for the dead celebrated with a sacrifice at Larentia’s grave on December 23, the time of the winter solstice. It is precisely during this time that the souls of the dead roam in Germany (and all of northern Europe)! The Lares, as Tabeling shows in his third chapter (to which special attention is drawn), were originally identical with the laruae, i.e., ghosts of the dead. They were also called maniae, a word that cannot be separated from manes, which refers to spirits of the underworld. Another festival of the Lares that also takes place around the winter solstice is the Compitalia, during which masks (maniae) made of wool were hung on doors in honor of the Lares and Mania. Tabeling notes that larva can also mean "mask." This leads to connections far beyond what Tabeling discusses. He compares this to the "Harlequin," the always masked devil of medieval plays, who was originally the leader of the Wild Hunt (the army of the dead) in France. Furthermore, Tabeling points out that the German word "schemen" (phantoms) means both ghost and mask. The classical philologist, in particular, is reminded of the swarm of laruae. Again and again, throughout his study, Tabeling discusses the connection between the Mother of the Lares and Hekate. The Lares, who later wore dog skins or were accompanied by dogs, were originally dog-shaped souls of the dead, just as Hekate herself appears in the form of a dog. At this point, the clear association with the Wild Hunt should have been made, where dogs always accompany the dead and are generally interpreted as spirits of the dead. Additionally, this army of the dead frequently has a female leader (Perchta, Frau Gode, etc.).

Furthermore, especially during the wintertime, when the main festivals of the Lares and their mother took place, ecstatic cult celebrations also occurred at this time. These continued secretly in Germany, as a forthcoming ethnological study will likely show, until recent times. Compare the Perchten dances, in which masks play such a significant role. All this is to be understood as follows: Even the living can join the raging host of the dead souls if they succeed in transformation. This is indicated by the donning of the mask: no longer human, but transformed into a demon, the mask wearer mingles with the wild host. Where they pass through, corn grows in abundant richness. A strip of tall, vigorous grass reveals the trace of the Wild Army...

From all this, a very important conclusion can be drawn regarding the derivation of the Latin word manus (manuus, manius, mana, mania, manes, etc.), which seems inseparably connected to the Germanic manu (in mannus, "primordial human, ancestor" cf. mensch, i.e., manisko, "descendant of Mannus") and the ancient Indian manu-manus (primordial human, judge of the dead). See my treatise on Janus, note 163 – Latin manus originally referred to a blessing-bringing spirit of the dead, then simply (not inversely!), and the root of the word (man-) is likewise present in, for example, Greek μαίνομαι (mainomai), to rage, to be wild, to be out of control, to rave; μανία (mania), madness, frenzy, possession, inspiration; μαντις (mantis), seer (= divinely inspired) among others. Thus, manus means "one from the raging host, one from the wild troop."

We hope that after Tabeling’s valuable study, a larger, perhaps definitive work on the Lares will follow, which will also take into account the Germanic-German tradition, whose treasures are known to few, in a richer context.

Dr. Otto Huth (Bonn).

-

Seeger, C., Prehistoric Stone Structures of the Balearic Islands (Including the notes of Dr. B. Seeger, with pictures (12 plates) and lists by Dr. B. Seeger and C. Seeger, Leipzig, Rochler & Amelang (1932), 123 pages, large 8°. Cloth-bound, 4.80 RM.*

The first part covers the smaller island of Menorca in twelve sections (pp. 1-104), while the second part (pp. 105-124) covers the larger island of Mallorca in four chapters. The apparent contradiction is explained by the fact that Menorca, due to its much more limited economic potential, has preserved its monuments significantly better, though they are not completely intact there either. The numerous pictures provide a rather good impression of the different types of megalithic stone structures on the islands. The purpose of the book is to offer a supplement and to encourage one's own work, rather than a systematic examination of the individual monuments and their classification into broader contexts.

At the same time, the book (in the first section and scattered throughout) provides highly useful practical remarks for a visit to the islands from someone thoroughly familiar with the land and its people; tips that will surely save a visitor many mistakes. However, it would be desirable for the archaeological map of the island of Menorca to be presented in a form that truly allows for practical use, and similarly for the works mentioned in the text to be compiled somewhere in an overview. The lists of the various monuments (with location details) are very useful.

This review cannot address individual questions; it must be limited to a brief enumeration: caves and niches, shaft tombs, megalithic dwellings, salas hipóstilas (semi-underground columned rooms), talayots (huge tower structures with a circular base), potarrás (massive well systems), taulas (enormous single-stone tables, unique in the world), Cyclopean walls, nauetas (a type of vaulted structure, with a ground plan resembling a compressed horseshoe; based on the finds, they are likely graves; some consider them solar sanctuaries), and finally the frares (a type of stone column made from one or more stones). Perhaps Germanien will later publish some illustrations.

The Balearic Islands, along with Corsica, Sardinia, today only known for their prehistoric sites to antiquarians and specialists, may one day provide crucial insights into the path of human culture, and upon closer inspection, one recognizes that they are more distant from the North in space than in substance.

F. Friedrich.

-

Bernhard Nunner, Hearth and Altar: Transformations of Old Nordic Deities in the Conversion Era. 1st delivery: Introduction, Leipzig 1933 (A. Klein Verlag), 24 pages, 8°. Price: 0.60 M.

The long-awaited and highly significant new work by Nunner has just begun to appear in installments. The introduction is now available, and during the course of this year, 5 volumes will follow, each priced at 2.50 M, with a subscription to the entire work costing 2.00 M. The starting point of the investigation is Old Iceland, that is, the living Germanic world as we can come to know it from the sagas. The subject is the transformation of customs during the conversion period. As the well-chosen title suggests, Nunner seeks to understand these transformations as a result of religious change and religious losses. In my view, this approach is indeed crucial. One can look forward to how this will be developed.

Nunner sets his goal very high: ultimately, he intends to provide a historical foundation for our "national ethics." The highlighting of the Germanic ethos is meant to be a guiding force in today's confusion. This much is already clear from the introduction: here, ingrained errors, to which the previous view of history had succumbed, are rigorously corrected. The fact is confirmed that German history can only be properly understood from its Germanic roots, which had previously been denied. We consider Nunner's approach of reinterpreting German history through the lens of Iceland as the last bastion of Germanic culture to be entirely justified. However, we do not believe it is the only path.

Nunner runs the risk of falling into an overly one-sided perspective. He underestimates both the significance of German folklore and the Indo-Germanic comparison and ethnology, which has long moved beyond the search for individual parallels to compare larger complexes in order to grasp cultural cycles. Nevertheless, this in no way diminishes the value of Nunner's findings. The path through Old Iceland is still too little known, and much remains to be done here.

Dr. Otto Huth.

-

Bürger, Willy, Johann Carl Fuhlrott: The Discoverer of the Neanderthal Man. Wuppertal-Elberfeld, A. Martini & Grüttefien, 1930, 40 pages (with 3 illustrations), large 8° (pp. 36-39 contain a chronological list of Fuhlrott's publications), 1 RM.

There is hardly a prehistory book where Fuhlrott’s name is not mentioned, but, well-known as the name is, there has so far been a lack of a comprehensive presentation of his scientific activities, which culminated in the discovery of the Neanderthal man and the correct identification of the bone remains. Bürger provides this account with commendable clarity and factual accuracy, corresponding to Fuhlrott’s life. Fuhlrott, who could be called a "Studienrat" by today's standards, worked in a time when narrow specialization had not yet replaced versatility. Thus, his zoological, botanical, and geological works are discussed, with particular emphasis, of course, on his work in cave research.

Especially enlightening is the report on the lively scientific debate that arose around the Neanderthal remains—mostly against Fuhlrott, who correctly recognized their temporal and evolutionary significance. One point we would like to emphasize: "It is noteworthy that the well-known English geologist Lyell (in England, the significance of the find was recognized early on) was the only researcher who found it necessary to personally inspect the discovery site." After half a human lifetime of struggle, Birdhow delivered his devastating verdict in 1872. For a full generation, there was silence, enforced by authority, until at the beginning of the 20th century, Schwalbe and Klaatsch took the scientific risk of a new investigation, finally bringing Fuhlrott’s view to recognition in Germany.

Suffert.

-

Hend, Hans, Armin the Cheruscan. A Novel. 1st edition, Leipzig: Staadmann Verlag, 1932. 337 pages, 8°. Price: 4 RM; Cloth-bound: 5.50 RM.

Hans Hend, the son of historian Eduard Hend, wrote a book that particularly appeals to those interested in Germanic prehistory. According to the author, among the key influences in writing his book were the works of Rosinna, Aummer's "The Decline of Widgards," but primarily Teudt's "Germanic Sanctuaries." By incorporating the insights of these prehistory scholars into the portrayal of the cultural state of Germania during the time of Arminius-Erminos, this novel sets itself apart from the numerous other books (especially youth literature) that have poetically exploited the era of conflict between the Romans and the Germanic tribes. Additionally, Hans Hend proves himself to be a truly German poet, presenting us with a vivid depiction of Arminius's time, one that, shaped by his poetic prowess, speaks with striking relevance to us today. The heroic leader Arminius emerges, fighting for the unity and freedom of the Germanic tribes, yet dying with the cry: "Tiusland! Tiusland! When will the Reich come?"

We can warmly recommend this work of German literature by a living German poet to all our friends.

-

Edmund Kiss, The Glass Sea. A Novel from Prehistoric Times. Leipzig, 1930, Roehler & Amelang, Publisher. Hardcover: 5.40 RM.

A tragedy of the Earth and humanity from prehistory comes to life here, scientifically based on the premise of the catastrophe theory and the associated flood theory (World Ice Theory), which, viewed from a cultural-historical perspective, touches on new ground in the research that extends human prehistory far beyond our usual historical field of vision.

-

Edmund Kiss, The Last Queen of Atlantis. A Novel from Around 12,000 B.C. Leipzig, 1931, Roehler & Amelang, Publisher. Softcover: 3.30 RM; Cloth-bound: 4.80 RM.

As a scientist, explorer, artist, and architect, the author has traveled the Andean land and followed the traces of a distant past with the confident instinct of having discovered a part of the globally spread Atlantean culture. He sensitively portrays the geological events that disrupted this culture and how it nevertheless preserved itself in the Nordic soul. One senses that a part of that same soul is alive within the author, a soul that we must rediscover today. Hans Wolfgang Behm has contributed a detailed afterword to both "The Glass Sea" and this novel, clarifying the scientific aspects underlying the material.

-

Groh, Georg, Godless Theology. Rig-Verlag Schweinfurt, 8 pages.

A sharp philippic, a reckoning with godless theologians who feel the need to inspire and defame a German faith. It is a rather sad chapter and does not align well with true "peaceful tolerance" when one occasionally hears the response to Hermann Wirth’s "What Does it Mean to be German?": "I can do without such Germanness." A contribution to the problem of Germanness and Christianity, and certainly not a poor one. An eye-opening piece for those in doubt.

Review of Periodicals:

Germanic Migration Paths and Tribal Cultures

Gustaf Rössinna, The Map of Germanic Finds in the Early Imperial Period (circa 1-150 AD). Introduction by Crest Petersen in Breslau. Mannus Vol. 25, Issue 1, 1933.

In the latest issue of Mannus, an important posthumous work by the late master of Germanic prehistory research, Gustaf Rössinna, has been released to the public. This work focuses on the find locations of the free Germanic tribes in the so-called early Imperial period. Rössinna had worked on this map for nearly ten years without being able to publish it, given certain unavoidable shortcomings in the current state of research. The map, which shows the tribal divisions of the Germanic peoples during the first century and a half of our era, illustrates three major tribal confederations: the Ingvaeones, Irminones, and Istvaeones. The map highlights a close alignment with the accounts of contemporary Greco-Roman writers, while archaeology provides more precise details. These major confederations and their territorial settlements are clearly recognized.

-

Karl Waller, Chauci Burial Fields on the North Sea Coast. Mannus Vol. 25, Issue 1, 1933.

Previous efforts had been unable to fully understand the Chauci tribes either through written records or archaeological excavations. However, Waller's investigation of the burial fields at Silberberg near Sahlenburg and other sites has helped illuminate the distinct burial customs and ceramics of the Chauci, and he traces their spread as far as Holland. He proposes that the Chauci were pushed into the marshlands by the advancing Saxons, where they settled while the Saxons remained on the higher land.

-

W. Gaerte, The Eastern Boundary of the Gothic Vistula Culture in the Roman Imperial Period. Mannus Vol. 24, Issue 4, 1932.

Recent finds allow for a closer definition of the eastern boundary of the Gothic settlement area in East Prussia during the early post-Christian centuries. This boundary extends from Braunsberg along the Passarge River and beyond Passenheim, with the Galindians and Sudavians occupying areas to the east.

-

Walther Schulz, Germanic Tribes between the Elbe and Vistula from the 5th to 7th Century. Volk und Rasse Vol. 8, Issue 2, 1933.

Contrary to the widespread belief, particularly stressed by Polish research, that the Slavs settled in a completely depopulated eastern Germany, Schulz demonstrates that significant Germanic populations remained. These populations, though scattered, gradually merged with the Slavs, and evidence for their presence can be seen in numerous Germanic finds from the region. The continuation of old Germanic names in Slavic forms also supports this.

-

Fritz Wiedemann, Are the Upper Silesian Wooden Churches Remnants of Germanic Cultural Heritage? Volk und Rasse Vol. 8, Issue 2, 1933.