Hitler at the South Pole

by Ernst Zündel

Foreword

It is typical of our time that in order to be heard, one must resort to rather unusual methods. One would actually assume that in our age of lightning-fast, wireless communication, through radio, television, teleprinters, and telephones, not too many things could remain secret for long, or even be suppressed. Today, almost everyone knows everything about everyone else. Argentinians know what happens in Germany, Australians know what happens in America, and we, the white people in America, Canada, and Europe, know within a few hours if anything happens to a Negro terrorist in a prison in Africa. So one would think that universal reporting, which has turned the world into a "global village," would be a wonderful tool for raising the general knowledge of all peoples! At least, that's how the liberal dreamer, the uncritical idealist in the West, sees it. The people living under the red terror of opinion control also know this, but they see it less idyllically, and they know that in the communist state, the transmitter of news, i.e., the state itself, controls all the information that the receiver gets. Therefore, they are skeptical and develop an extremely watchful eye to learn to distinguish between lies, half-truths, facts, and propaganda tailored to specific purposes. For the reader in the communist sphere of power, reading between the lines is often more important than reading the actual lines.

In the "free world," where everyone from the rooftops and politicians of all ideological shades loudly proclaims that freedom of speech exists, censorship does not, and everyone is free to express their opinions. It sounds so wonderful and looks so great on paper that almost every state today has included it in their fundamental laws and constitutions. The right to free expression is officially guaranteed to the Chinese in Red China, just as it is to the Soviet Russians and the Palestinians in Israel, the Germans in the "GDR," or the so German and so democratic citizens of the rule-of-law state this side of the minefields and death strips. This sacred right is even enshrined internationally in the United Nations Charter, thus accepted worldwide—on paper, of course!

If you are lucky, you may be able to express your opinion freely, but what good does that do for you or your ideas if (a) no one is present when you express them, or (b) if they listen but don't understand you due to linguistic or content-related reasons, because they lack the necessary historical, scientific, or educational background? Or what happens if the person listening to you understands everything but holds an opinion diametrically opposed to yours? When that happens, there are only three possibilities: (1) They listen to you and simply say, "What nonsense," and that is the end of your freedom of expression. (2) They could cause you trouble because of your statements by slandering, betraying, or even legally prosecuting you for insult, incitement, hate speech, or conspiracy, depending on the content of your expression. So, in the second case, your freely expressed opinion can be quite dangerous! That's why staying silent, often seen today as nearly a "first duty of the citizen," is equally popular in both East and West. (3) But if, against all odds, you find a good and intelligent listener who takes your expressed opinion for what it is—something personally experienced or personally learned—then the course is set, and the possibility exists that the freely expressed opinion will continue to spread, constantly challenged and modified, and finally find a larger audience, becoming an integral part of common knowledge. Wonderful! That's how it used to be, and that's how it could be if we had already arrived in the paradise of liberal dreamers.

In today's world, however, the harsh reality is that certain intellectuals, of particular ideological orientations, have infiltrated the vast majority of mass media and are thus able to sort, edit, condense, and filter everything, heavily influencing—meaning, in truth, manipulating—the media and the information they produce. Press agencies, whose reports are simultaneously sent worldwide via teleprinter, operate in this way. Telegraph agencies work the same way, and thus, news is either transmitted or printed truthfully, twisted, or not at all. If a single ideology dominates or is prevalent at the moment, for example, in today's Germany, only good things about Jews are reported, while only bad things and gruesome stories about the evil Nazis are brought to the public, just as Dr. Goebbels had little good to report about Jews.

In addition, in both the West and the East, the dominant ideology is accompanied by racial elements and religious orientation, or even the economic views of the news transmitter—from the reporter to the newspaper owner, or in North America, the owner of the radio or television network—and it becomes easy to see that free expression of opinion might exist here and there, but there is no free dissemination of opinion, accessible to all and censored by no one, anywhere today, nor is there likely to be in the future.

We are all subject, in the East and the West, more or less openly or covertly, to censorship—sometimes by individuals, sometimes by interest groups, economic blocs, parties, ideologies, or states. To break through this existing censorship, in the case of Germany's Antarctic claims, this book was partly rewritten and reissued. Why a book in the German language had to be published in distant Canada about Germany's territorial claims in the even more distant Antarctica is also a sign of the times.

The deep slumber that seems to have fallen over broad sections of the populace and leadership in the three German states since 1945 is to blame for this. On one side, the over-satiated, intellectually lazy West German citizen, made complacent by the economic miracle, is at fault, and on the other side, the DDR official, who wants to be even more papal than the Kremlin's pope to his red advisors in Moscow, shares the same guilt. The proportional compromiser in Austria also does not seem inclined to let his gaze wander beyond the Alpine mountains to distant continents, even if perhaps the survival of his own people could be decided there.

This world-weariness of the three German states is the true great tragedy of the post-war period and is unfortunately all too characteristic of the last thirty years. This book aims to lift the veil of silence and break through the invisible censorship that, perhaps within a generation, could strangle the life of the Germans due to a lack of raw materials and the need for expansion.

With this book, a new generation asserts its claim to a vast area of Antarctic territory that the Germans explored and mapped in great detail with many dangers and at great expense. Especially now that the great international debate has erupted over how Antarctica should be divided, who owns what, and who has claims to which regions, why, and for what reasons, it is now high time for us Germans, in all three states, to quickly reassert our right to participate in those discussions down there in the last uninhabited continent. The censorship of the Allies has nearly succeeded in denying the Germans the fact of their claims. Through legal, diplomatic, and propagandistic tricks, they want to cheat Germany out of its rightfully earned claims in Antarctica.

Much like tsarist Russia dealt with a weakened China, they want to handle German interests since 1945 in the same way. That the Allied-installed governors of German nationality first dealt with rebuilding after the total collapse is understandable. That, considering the circumstances and the limited manpower and leadership material that survived the war, no grand world politics could be conducted at the time, is also understandable. Today, however, the German states have grown strong again, thanks to the industriousness and work ethic of their citizens, and thus have the right for their economic and political interests to be recognized worldwide by the respective governments in Bonn, Pankow, and Vienna! Just as today's resurgent China actively asserts its interests worldwide through missions, delegations, visits, advisors, trade agreements, and military activities, so too must the Germans learn once again to stand tall with heads held high, as equals among nations.

How This Book Came About

I am a German, born in 1939. I grew up in a small German village and emigrated to Canada before I was even 19 years old. Until my emigration, I lived like most Germans at the time, always on the brink of hunger, regardless of age. My main focus was on survival, moving forward, and, after completing my apprenticeship, experiencing things for myself!

It was the time of large advertisements in German newspapers and magazines calling for "immigrants wanted" to Canada, America, Australia, Argentina, and South Africa. After reading the colorful brochures that painted a world of endless expanses, wild mountains, shimmering lakes, adventures with Indians, bears, wolves, canoe trips, and campfires à la Karl May, the decision to emigrate was quickly made. Wanderlust drove me, and the eternal dream of youth to conquer the world did the rest.

So, I found myself, wide-eyed, cold, and hungry, one morning at four o’clock, 5,000 kilometers away from home, lonely, a bit frightened, and all alone in front of the main train station in Toronto, Canada. I could only speak a few scraps of English, just what a distance course for tourists had taught me. I had no acquaintances, friends, or relatives anywhere in Canada. I didn’t have a job either. In my suitcase, I carried an axe and work clothes for a lumberjack, in case I couldn’t find work in my trade as a graphic designer. In my pocket, I guarded my $200, which I had painstakingly saved and exchanged ... the dollar was worth DM 4.36 at the time. It was my entire treasure, not even enough to get back home. So, there was no turning back.

After some fears and hesitation, the will to survive quickly took over. Soon, I found a room with "running" water that flowed into old buckets, cans, and bowls from several spots in the ceiling whenever it rained! But the landlady was charming and, most importantly, spoke "German," though in a peculiar dialect I couldn’t place anywhere in the German regions I was familiar with. Later, I learned that what I was muddling through with my landlady was nothing other than Yiddish. Thus, I saw and experienced my first Jews.

I soon found work, thank God, in my profession. My thorough German apprenticeship helped me land a good "job," and learning English posed little difficulty. As I began to understand the new language, a whole new world opened up to me. In further education courses and evening schools, I met young people of other races and nations. In one English class, there were no fewer than 32 participants from 21 nations.

Contact with peers of both sexes brought me into contact with a beautiful French woman, and soon the greatest adventure on earth—marriage—was on the horizon. Communication was in English at first, but soon in French, and more and more horizons and deeper insights into the soul and mindset of my new home opened up to me.

At first, I was astonished, then bewildered, and finally horrified by what I discovered. Canadians and Americans, whose radio and TV programs could be received without any trouble in Toronto, lived in a completely different mental world from us Germans. What I experienced back then is called "culture shock" today.

I couldn’t believe it was possible for adults, seemingly intelligent people, to be so politically naïve and so poorly educated in history. I decided to get to the bottom of it. I began an intensive study and devoured the Toronto library.

Professionally, things were going well. In the meantime, I had a son, and with full confidence, I made the decision at the age of just 21 to start my own business.

By that time, I had mastered the English language, and thus I was drawn to Montreal, the largest French-speaking city outside of France. Without hesitation, we moved to Montreal, in the province of Quebec, and I began my language studies anew while working independently in my profession.

Once again, I experienced a great shock, this time in learning French. Here, the separation from the German worldview and post-war reality that I was familiar with was even more striking, and the gap even wider.

Through my profession, I earned good money and was able to go on study trips by car, often for months, across Canada and America. I got to know the great thinkers, historians, politicians, and church leaders, often in interviews or private meetings. My theoretical history studies, particularly about the period after the turn of the century in Europe and America, were reinforced by several years of studying political science at the University of Montreal.

Alongside this packed program, I wrote articles for Canadian, German, and American magazines. Soon, my book collection needed its own room, and my files required entire rows of folders.

One of those files was on Hitler, and what initially irritated me and later fascinated me was the possibility of Hitler's survival, which was often discussed in the foreign press. Like most post-war Germans, I grew up firmly believing that the "bloody dictator and tyrant met his well-deserved end on April 30, 1945, in Berlin." In all my years, I had never met a German, regardless of age, who didn’t believe the same. Everyone was absolutely convinced of Hitler’s suicide. However, I found the English, French, Canadians, Americans, and especially Jews to be equally convinced that Hitler had escaped from Berlin.

Not a month went by that I didn’t hear on the radio, see on TV, or read in newspapers or magazines that Hitler, Bormann, Mengele, or whoever else was alive and well, living in luxury in hidden haciendas or estates in South America. Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal often made headlines and is still a frequent guest on American and Canadian television. He seemed to have good sources, which often led to the arrest, deportation, abduction, or even assassination of former SS, Gestapo, or Wehrmacht members.

Through reports from—and correspondence with—Germans in South America, my suspicion grew that there might be some truth to the wild stories of the Americans and Jewish Nazi hunters.

Part of my research resulted in the following documents, which I present to the German reader and skeptic only because these articles and reports brought me into contact, for the first time, with the historical fact of the "German Antarctic Expedition," about which I had learned nothing in school or anywhere else in Germany. Now, questions began to arise that sought answers. To save space, I will refrain from a literal translation and will instead translate the content meaningfully, with particular reference to the source and the date of the cited news.

Time Magazine (America’s equivalent of Der Spiegel) published a report on May 7, 1945, on page 70, under the headline "Hitler Story," based on information from the "Free German Press Service" in Stockholm, often cited and printed in America during the war. Figures like Wehner and Brandt were allegedly close to it. The report stated: "The ‘Hitler’ who was in Berlin was not Hitler at all, but a grocer from Plauen named August Wilhelm Bartholdy, whose misfortune was that he looked exactly like Hitler. Bartholdy was well and thoroughly trained for his role and then ordered to Berlin to heroically die on the barricades ... He was Hitler’s trump card, with which he could weave a heroic legend around himself and his death in the ruins, while the real Hitler escaped underground and would carry on."

Reich photographer Heinrich Hoffmann was also mentioned. His task was supposedly to document everything photographically.

Since Time Magazine was one of the most conservative journals in its field and subject to the same American wartime censorship as all other newspapers, it is surprising that such a story was allowed by official censors.

Shortly thereafter, an article appeared on the front page of a major daily newspaper in Buffalo, New York, with the headline: "Local Man Sends Truman $5,000 to Start a 'Catch Hitler Reward Fund'." The article further reports: "Attorney William J. Brock, believing that Hitler survived and is being hidden and protected by his followers, today sent President Truman a certified check for $5,000, which was intended as the initial capital for a reward of $500,000 for those who would deliver Hitler to the Allies for trial."

According to recurring newspaper reports, Hitler was still alive and might one day emerge from the underground. This article was circulated worldwide by major news agencies at the time.

Then follows the frequently cited suspicion of all Allied powers that Skorzeny might have contributed to Hitler’s escape, and indeed may have even smuggled the real, genuine Hitler out of Berlin. Skorzeny, by his own account, was in Berlin until April 10, 1945.

In the book by an Englishman, Charles Foley, about Skorzeny, Commando Extraordinary, Ballantine Books, pages 134-135, we read: "Skorzeny voluntarily surrendered to the Americans in the Alpine region after the end of the war. One of his first interrogators was none other than the head of counterintelligence for General Eisenhower’s Supreme Allied Command, personally. For six hours, Skorzeny was cross-examined by him. At the end of this marathon interrogation, the counterintelligence chief suddenly asked Skorzeny: 'What were you doing in Berlin at the end of April?' Skorzeny replied that he wasn’t there. The counterintelligence chief then mustered all his interrogation skills and pressed further: 'Come on, you know full well that you personally flew Hitler out of Berlin on April 30. Where did you take him?'"

Skorzeny denied the whole story. Nevertheless, he was asked the same question hundreds of times, repeatedly, by GIs and generals, reporters and judges, by the British, French, Russians, and everyone else who had the chance to ask. Even up until shortly before his death, thirty years after the war, he was still asked: "Where did you really leave Hitler?"

Skorzeny always answered the same: "I am sure Hitler is dead. If I had brought Hitler to safety, why would I have voluntarily returned to American captivity?"

To which most of his high-ranking visitors and interrogators always replied: perhaps he returned voluntarily precisely to divert Allied search parties from Hitler's real trail? After all, he was a fervent National Socialist and admirer of Adolf Hitler.

From Skorzeny’s own books and articles, we know that the American Counter Intelligence Corps (C.I.C.) repeatedly interrogated him and also Hanna Reitsch after 1947-48 about how, where, and when they smuggled Hitler out of Berlin.

What possibilities still existed at that time for such a deception and escape operation will once again be indicated from several mostly Allied sources. On September 17, 1974, at 7:15 p.m., on the Canadian radio program As it Happens from C.B.C. Radio, a professor from the dental faculty of the University of California in Los Angeles stated that Hitler ordered a special plane to fly to Berlin with the task of removing all X-rays and other documents about the health of the higher party and state leaders to an unknown destination. Therefore, all drawings and documents are recreations by assistants from memory of the originals. From the German side, for the last 30 years, a picture of total chaos has been spread about the events of that time. From the Allied side, it looks quite different. The French flying ace Pierre Clostermann, bearer of the D.S.O. and D.F.C., reports in his book, The Big Show, published by Corgi Books, on page 238, under the heading "The Last Test, May 3, 1945," about the situation in northern Germany and Denmark: "The evacuation of the Luftwaffe was carried out in perfect order. All airfields in Denmark were overcrowded with German transport and fighter planes. There was enough fuel to guarantee effective defense for quite some time."

A large naval convoy from Kiel and an endless stream of airplanes over the Skagerrak, as well as the tenacious defense of the ground troops, were clear witnesses... of the German will to defend."

On page 244, he reports on an air battle that was common only at the beginning of World War II when Germany held air superiority: "Near Fehmarn, close to Heiligenhafen, we suddenly encountered the large airbase of Grossenbrode with its seaplane bases and runways, overflowing with heavy, multi-engine transport aircraft. Several ships were anchored off the coast. As we broke through the clouds in our Tempest machines, we were suddenly surrounded by swarms of German fighter planes, in groups of 30 to 40. About 100 German fighters were in the air. On the airfield or taking off, there were more than 100 large transport planes. I had only 24 Tempests."

He then continues to describe how he saw a whole row of enormous Arado 232 transport machines, with their two decks and 24 wheels, sitting on the runway.

This was the enemy picture, as seen and described first-hand by the world-renowned Frenchman Pierre Clostermann on May 3, 1945. Could Hitler have escaped from Berlin in a jet plane with appropriate fighter protection, if such a wish or plan existed?

But back to other witnesses. H. Trevor Roper, who, as an Oxford professor and Germany expert, was part of British Intelligence, mentions in his book The Last Days of Hitler on page 101, Heinrich Himmler's remark: "The Führer has some sort of plan." Goebbels also expressed himself in similar terms at the end of April with these words: "Germany is still the land of loyalty! It will celebrate its greatest triumph in danger!"

Hitler supposedly committed suicide with Eva Braun on April 30, 1945, at 3:30 p.m.

The book The End of the Hitler Myth mentions on page 339 that Hitler arrived at Tempelhof Airport at 4:15 p.m., so 45 minutes after his death, he was still alive! According to Mattern in his book UFO: The Last Secret Weapon of the Third Reich, on page 48, he cites the Chilean newspaper Diario Ilustrado of January 18, 1948, which prominently reported the following, based on a sworn witness statement:

"On April 30, 1945, Berlin was in full dissolution. But little of this was noticed at the Tempelhof airfield. The ground organization, such as harbor signals, radio, and navigation aids, gave the pilots all the instructions needed for smooth landings. It was very busy. Every six minutes, a plane landed. Ten planes took off every hour, sometimes more. Fast fighters of the German Luftwaffe raced across the horizon, securing the airspace. As a result, the airfield suffered no major damage. Amid the roar of engines, one could hear the harsh hammering of the onboard weapons and the approaching sound of battle. Reports came in that the Russian army had already advanced to Kochstrasse and Oranienstrasse. The connection to the city center was cut off. There was only one escape route left: by air, or capture. In the next few minutes, the feverish pulse of Tempelhof airfield would cease. At 4:15 p.m., a Ju 52 landed, hastily bringing 55 soldiers from Rechlin to defend Berlin. They were all boys under 18 years of age.

On this plane, as a gunner, was Engineer B., whom I had known for years and for whose military exemption I had repeatedly intervened. He was eager to refuel and get out of Berlin as quickly as possible.

While refueling, he suddenly received a sharp nudge from the radio operator, directing his attention to a specific spot. At a distance of 100 to 120 meters, he saw a Messerschmitt turbine jet, Type 332. With an auxiliary tank, this plane had a range of 4,000 kilometers. Engineer B. and his comrade, the radio operator, attentively watched the plane with their sharp eyes. Before it, unmistakably, stood their supreme warlord: Adolf Hitler!

He was in field-gray uniform and was gesticulating animatedly with some party officials, apparently bidding them farewell. For ten minutes, the two men observed the fleeing Führer closely amid the haste of refueling. Then the fuel was loaded. At 4:30 p.m., their plane took off again. Seven and a half hours later, at midnight from April 30 to May 1, 1945, Admiral Dönitz announced over the military radio that Hitler was dead and that he had taken command. A few minutes later, German radio broadcast the same news. Goebbels also announced that the Führer had entered Valhalla. According to a report from the Soviet Union's information office on May 3, 1945, Fritsche stated during his interrogation after his capture that Hitler, Goebbels, and the newly appointed Chief of the General Staff, General of the Infantry Krebs, had committed suicide.

Lieutenant Colonel Heimlich of American Intelligence, who investigated all reports of Hitler's death, concluded that Hitler, Eva Braun, and Bormann were still alive. There was not a shred of evidence that Hitler was dead. The report (INS) also stated that the U.S. Army's investigation into the events of the last days of fighting revealed that it would have been extraordinarily easy to escape from Berlin. Experts also pointed out the impossibility of completely burning a body in the open without leaving remains. A working party of American, British, French, and Russian soldiers discovered a pit containing two hats supposedly belonging to Hitler, as well as a pair of underpants with Eva Braun’s initials; however, no bodies or remains were found.

Engineer B. rules out any mistake on his part and insists emphatically that on April 30, 1945, when he landed at 4:15 p.m. and observed Hitler in the bright light of the setting sun, it was no longer possible to reach the Reich Chancellery. For this reason, it could never be true that he committed suicide in the Reich Chancellery on that day. When Engineer B. heard the radio announcement from Admiral Dönitz, he was extremely surprised and at first thought that the Führer had died in a plane crash."

Once again, major American news agencies such as "Associated Press" and "United Press," which were published all over the Western world except in occupied Germany, which was under strict censorship, ran detailed stories about the events in Berlin in late April 1945. On January 16, 17, and 18, 1948, they published the story of a German flight captain, Peter Baumgart. As it was clearly stated under his photo in a leading article in the Chilean magazine Zig Zag on January 16, 1948, Baumgart claimed to have flown Hitler and Eva Braun, along with other loyalists, from Tempelhof to Tondern on April 30, 1945, and from there, with another plane, over the Skagerrak to the Norwegian port of Kristiansund, where a submarine flotilla had been waiting for the Führer since April 24.

The American news agency AP reported on December 4, 1947, from Warsaw, regarding a sworn statement during a trial before a Polish court, that an SS captain, P. Bandgart, testified that Hitler had sailed to South America on a German submarine two days before the fall of Berlin. Whether this was the same Baumgart mentioned in the above article could not be determined after 30 years.

Under the headline, "German Tank Man Claims He Saw Hitler Escape," on January 17, 1948, the American news agency United Press published an eyewitness report in Chile stating that Hitler left the Reich Chancellery on April 29 in a "wounded transport tank."

The American news agency Associated Press, on March 5, 1948, under the headline "Hitler Escaped," mentioned that a German girl denounced a Luftwaffe pilot to American Army Intelligence in Nuremberg, leading to the arrest and interrogation of a Luftwaffe pilot named Arthur Frederick Angelotte Mackensen in Wollfrathshausen near Munich. He claimed that he had seen Hitler and Eva Braun fleeing Berlin by plane to Denmark at the end of April.

The Jewish writer and Ben Gurion biographer, Dr. Michael Bar-Zohar, in his book The Avengers, reports in precise detail that there was an escape or relocation plan at the highest level, which was prepared on August 10, 1944, at the Maison Rouge Hotel in Strasbourg in front of high-ranking Reich officials and German industrialists. The American intelligence service, the "Office of Strategic Services," soon uncovered this. Two main decisions were made: first, that part of the Reich’s wealth should be hidden within Germany, and second, that German capital should be sent abroad and invested there.

A report from the Allied intelligence services, transmitted to the U.S. State Department, detailed the German leadership’s plans for the postwar era. Everything was planned—from the use of German patents, whose registration in neutral countries increased dramatically in 1943-1944, to the establishment of German vocational schools and technical institutes in neutral countries, from where the work on German inventions and weapons technology would continue.

German foreign companies were to continue the Reich's research and production. German companies that had been seized by enemy states at the outbreak of the war were to be reclaimed after the war through legal proceedings financed by this "escape capital" or administered by proxies on behalf of the Germans. The necessary funds were already held in accounts in banks in Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Portugal, Spain, and South America.

The Allied intelligence services soon compiled a list of 750 companies headquartered in neutral countries that had been bought with German money. Switzerland accounted for 274 companies, Portugal 258, Spain 112, Argentina 98, Turkey 35, and others in South American countries. There were companies of all kinds—manors, airlines, shipping lines, railways, travel agencies, banks, hospitals, workshops, and more. One marvels at such foresight. Was this plan for the survival of Germany, even after a defeat in Europe, implemented?

Again, our prominent Jew should have his say. In the already mentioned book The Avengers, we read on pages 110-111 about Bormann the following:

"When the fighting ended in Berlin, some men of the Russian Fifth Army came across a burned-out tank at Spandau, and lying near it was the body of a man wearing a long leather jacket. In one of the jacket pockets, they found a small book which turned out to be the diary of Martin Bormann, the Führer’s deputy and one of the most astute of the Nazi Party leaders."

After the battle for Berlin had ended, some soldiers of the 5th Russian Army found a burned-out German tank near Spandau, and next to it lay the body of a man in a long leather coat. In one of his pockets, they found a small book. Upon closer inspection, it turned out to be Martin Bormann's diary. The dead man was not Bormann, as was soon verified, but an entry in the diary, in Bormann's handwriting, said: "May 1, attempt to break out."

How this relocation maneuver across the ocean to southern regions was supposed to happen is explained by Michael Bar-Zohar in his book The Avengers:

"A telegram that the Reichsleiter had neglected to destroy was found in his office: 'April 22, 1945. Agree with proposal of dispersal in southern zone beyond the ocean. Signed, Bormann.'"

These two sentences clearly conveyed Bormann's intentions to flee to South America and showed that he had begun to put his plans into effect on May 1.

Michael Bar-Zohar repeatedly mentions in his book, The Avengers, that there must have been a plan. He quotes Admiral Dönitz, who, during a speech in 1943, reportedly said: "The German U-boat fleet is proud to have built an earthly paradise, an impregnable fortress for the Führer, somewhere in the world." The Dutch-American writer Michael X, in his early 1960s work We Want You! Is Hitler Alive?, quotes a speech by Dönitz with nearly identical content.

Mattern, in his book UFOs: Last Secret Weapon of the Third Reich, on page 15, quotes Dönitz at a naval cadet ceremony in Kiel at the end of 1944 with the following words: "The German navy still has a great task to fulfill in the future. The German navy knows all the hiding places of the seas, and it will be easy for them to bring the Führer to safety, where he can calmly make his final preparations in case of extreme emergency." Grand Admiral Dönitz denies ever saying such things today and threatens legal action against anyone who claims otherwise.

However, Dönitz has yet to sue Michael Bar-Zohar, Michael X, or Mattern. Publishers are also unaware of any legal proceedings.

Mattern quotes from Erich Kempka’s book I Burned Hitler, on page 190, where Günsche, Hitler’s personal adjutant, allegedly shouted at Kempka with wide-eyed fury: "The boss is dead! I was stunned. Then I hastily asked: How could this happen? I spoke to him just yesterday! He was healthy and completely open."

On page 139 of the same work, we read further: "A German U-boat commander, during an interrogation by the C.I.C., stated that since April 25, 1945, his U-boat had been on standby in Bremen, at the Führer’s disposal. He declared that at least ten other U-boat commanders had received the same order!"

When asked about this, Kempka responded: "I could only smile wistfully." During the C.I.C. interrogation, it was further stated: "We have established that 12 flight captains were ordered to be ready for the escape of Adolf Hitler, under a secret order from the Führer’s headquarters."

In the Spanish book Hitler está Vivo, the escape or strategic retreat of Hitler and his loyalists is written as a fact. Special mention is made of an ultra-secret U-boat convoy that reportedly set sail from Kristiansund on May 2, heading toward South America. The book claims that two German U-boats, U-530 on July 10, 1945, and U-977 on August 17, 1945, surrendered to Argentine authorities. It turned out that these U-boats were crewed by improbably young sailors. Mattern describes this in his book UFOs: Last Secret Weapon of the Third Reich, on page 85.

The Argentine authorities found it interesting and noteworthy that none of the crew members were older than 27, except for the machinist, who was already 32. The captain was 25 years old, and the second officer on board, Felix Schubert, was only 22, while most of the U-boat crew were even younger. Later inquiries with the Reich Naval Ministry in Kiel revealed that Otto Wermoutt was not the correct captain of this U-boat and that U-530, like many others, was a double for the listed units. Otto Wermoutt also remarked that he was completely alone, as his entire family had died during the bombings of Berlin. The family circumstances of the other crew members were similar.

On August 17, five weeks after U-530 surrendered to Argentine authorities, a new sensational news story broke, reporting that another German U-boat, U-977, under Captain Heinz Schäffer, had surrendered at the same location under similar conditions. His crew numbered only 32 men, as 16 married non-commissioned officers had been dropped off in time along the Norwegian coast by order. This was proof that command and oversight extended even into the personal affairs of each individual.

Crew List of U-530

Officers: Captain Otto Wermoutt (25), Karl Felix Schubert (22), Karl Heinz Lenz (22), Petri Leffler (22), Gregor Schluter (32).

Non-Commissioned Officers: Jürgen Fischer (27), Hans Setli (26), Johannes Wilkens (30), Paul Hahn (45), Georg Rieder (27), Kurt Wirth (24), Heinz Rehm (24), Rudolf Schlicht (26), Rolf Petrasch (26), Ernst Zickler (24), Georg Mittelstaedt (26), Robert Gerlinger (24), Viktor Wajsick (27), Günter Doll (21), Rudolf Bock (22), Werner Ronenhagen (24), Arny Krause (25), Karl Kroupa (25).

Crew Members: Herbert Patsnick (22), Sigismund Kolacinsky (22), Friedrich Mürkedick (23), Arthur Jordan (21), Eduard Kaulbach (23), Rudolf Mühlbau (22), Franz Hutter (22), Harry Kolakowsky (21), Franz Rohlenbücher (22), Johannes Oelschlager (20), Willy Schmitz (21), Heins Hoffmen (20), Heins Paetzold (21), Gerhard Nellen (20), Ernst Liewald (21), Reinhard Karsten (22), Hans Wolfgang Hoffmann (22), Arthur Engelken (22), Hans Sartel (21), Erhardt Piesnack (21), Joachim Kratzig (20), Erhardt Muth (25), Friedrich Ourez (21), Werner Zerfaz (20), Erhardt Schwan (20), Hugo Traut (20), Engelberg Rogg (20), Franz Jendretzki (23), Georg Wiedemann (21), Günther Fischer (29), Georg Goebl (24).

Crew List of U-977

Officers: Captain Heinz Schäffer (24), Karl Reiser (22), Albert Kahn (23), Engineer Dietrich Wiese (30).

Non-Commissioned Officers: Hans Krebs (26), Leo Klinger (28), Erich Dudek (23).

Crew Members: Gerhard Meyer (23), Karl Kullack (21), Wilfried Husemann (20), Heinrich Lehmann (21), Rudolf Schöneich (21), Walter Maier (19), Rudolf Neumirther (20), Hans Baumel (21), Hermann Heinz Haupt (21), Hermann Riese (21), Johannes Plontasch (20), Heinz Blasius (21), Alois Kraus (20), Kurt Nittner (21), Heinz Rottger (20), Heldfried Wurker (19), Heinz Waschek (20), Kurt Naschan (20), Gerhard Eofler (19), Harry Hentschel (19), Helmuth Maris (20), Alois Knobloch (19), Karl Homorek (19), Heinz Franke (21), Adwin Baler (19).

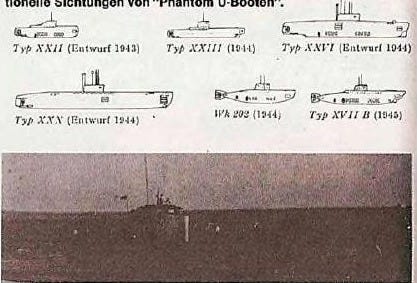

None of the massive U-boats, which were under construction during the war and which led Hitler to propose scrapping all large surface ships, ever fell into Allied hands. In contrast, units of this class were handed over to the occupying powers in Japan. The fate of these U-boats occasionally surfaced in the public eye, but they were typically described as "presumably of Russian origin" or as "unknown nationality."

Michael Bar-Zohar, the Jewish Ben Gurion biographer and specialist on Germany, who wrote a book about the Allied hunt for German scientists and had good contacts in both Jewish and National Socialist underground circles in Europe and overseas, reports on page 105 of his book The Avengers that:

"Two more U-boats, according to reliable sources, appeared off an uninhabited stretch of the coast of Patagonia between July 23 and 29, 1945. Two sailors from the Admiral Graf Spee, Dettelman and Schulz, who were sent to Patagonia by Captain Kay with several of their shipmates, later described their 'mission.' They were lodged at an estancia belonging to a German-owned firm, Lahnsen. From there, they were taken to a deserted part of the coast and saw two U-boats surface. The Graf Spee men went aboard the U-boats and collected some heavy crates which they ferried ashore in rubber dinghies. Then the crates were quickly loaded onto eight trucks and taken to the estancia, but very soon afterward, the trucks set off again with their load, heading inland. The rubber dinghies also served to bring about eighty people ashore, a number of whom were in civilian clothes. Judging by their manner of giving orders, they were obviously important people. They got quickly into cars waiting for them with engines running and were driven off."

After the Allied landings in Normandy and then in the south of France, the land route to Spain became impossible for the Germans, and Bormann gave orders for "Operation Land of Fire" to be continued by air. On May 22, 1944, Faupel had already sent the following letter to Dr. Hans von Merkatz at the Latin American Institute in Berlin:

"Reichsleiter Bormann, who has received two reports from von Leute and Argentine General Pistarini, requires the resumption of the transfers to Buenos Aires. Ask General Galland to place two aircraft at our disposal, solely for night flying, and to inform Rudel and Hanna Reitsch. The bearer of this letter, Kuster, must start preparations at once. Kohn must come on the first plane to assist Sanstede, who has been ordered to report here tomorrow."

“The planes took off from Berlin with crack pilots of the Luftwaffe at the controls Galland, Baumbach, Hans Rudel, and Hanna Reitsch, They landed at Madrid and then took off again for Buenos Aires.”

As far as Dr. Michael Bar-Zohar is concerned, regarding the possibility of a German plan: Was it the one that Bormann set in motion as "Operation Feuerland" on April 22, 1945? What role did the German Antarctic Expedition of 1938-1939 play in it?

I’m not sure about that! But one thing I do know is that absolutely incorruptible and highly renowned historians, writers, state officials, and other personalities have been occupied with the subject of a "Hitler escape" since 1945.

Again, let foreign sources and non-Germans speak about the real situation concerning Hitler’s corpse, that of Eva Braun, or even Bormann. First, regarding Reichsleiter Martin Bormann. The oft-declared-dead and much-hated shadow of Adolf Hitler has been circulating in countless articles, books, and press reports for over 30 years. Most of the time, he is said to be alive! Particularly, Jewish Nazi hunters, experts in their macabre trade, seemingly equipped with endless funds and access to the highest offices and most secret documents, insist that Martin Bormann and many of his party comrades and sympathizers not only escaped alive from Berlin and Germany but have also been living without financial concerns in South America for over 30 years. Especially the Hungarian Jew, Ladislas Farago, now living in America, is 100% convinced of Bormann's survival. His most well-known book, Aftermath, published by Avon Books, New York, in 1975, documents in a thick volume of 550 pages, complete with many photos and photographed documents, how Bormann escaped, how he fled to South America, and how he and his friends seem to have been protected by the highest authorities to this day. So, if Bormann managed to escape at such a late stage, is it not possible that Hitler and his loyalists could have also succeeded?

The American monthly magazine The Cross and the Flag, from April 1948 on pages 8 and 9, published a lengthy article written by Pastor Gerald L. K. Smith, in which seven theories about Hitler's death or escape are examined. He concluded that, based on the information available to him in America over three years (from the end of April 1945 to the end of April 1948), he was convinced that Adolf Hitler had escaped from Berlin to Argentina in April 1945!

He points to the book Frankly Speaking, the autobiography of the former U.S. Secretary of State under Truman, Jimmy Byrnes, in which he quotes a conversation with Stalin during the Potsdam Conference: "I asked Stalin, 'Marshal Stalin, what is your theory about the death of Adolf Hitler?' Stalin answered, 'He is not dead. He escaped to Spain or Argentina!'"

This rare book is in my possession. The passage is included in it. I find it unbelievable that such a sensational statement from Stalin, whose troops ultimately captured the Reich Chancellery and Führerbunker and examined them inch by inch, has not become more widely known. It must be emphasized once again that here the U.S. Secretary of State, at one of the most important post-war conferences, recounts a personal conversation with Stalin himself in his own autobiography. How much more official does it have to be for humanity to be convinced of a fact? Are there other ways to shed light on this dark history? Perhaps? Let’s take a closer look at certain details!

The Allies, from 1945 until today, have yet to produce a definitive document that informs all the nations involved in the war against Germany of Hitler’s death through indisputable evidence. This fact alone is unique in history, where the entire world fights a world war against the devil in person, only to move on without ever having proven him to be absolutely dead.

Goebbels was never believed in the enemy camp. He was always suspected as the master of lies, the fabricator of webs of falsehoods, and the orchestrator of the wildest rumors and legends. And yet, this same world accepts the Wagnerian ascension of his operatic hero and Führer, Adolf Hitler, who rises from the smoking ruins of his capital up to Valhalla.

To this day, the world accepts the "Goebbels version" of Hitler's death, with a few cosmetic adjustments, of course. Hitler must not go down in history as a hero but rather as a cornered suicide. Soon after the defeat, they even produce a pair of Eva Braun's panties with her embroidered name and a hat belonging to Adolf Hitler.

Rumors chase rumors, former servants, adjutants, dental assistants, and so on are interrogated and confess. Anyone familiar with the methods of the victors of 1945 won’t be surprised as to why. All more or less agree with the Goebbels legend about Hitler's death. The Russians collect hundreds of corpses in the vicinity of the Führerbunker. Entire battalions of women dig up every inch of ground around the Reich Chancellery, searching for the bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun. Several "Hitler bodies" are found. Several different ones are positively identified as "the Führer" by members of his entourage.

The world-renowned American author Cornelius Ryan, in his book The Last Battle, published by Pocket Book by Simon & Schuster Inc. in 1966, reports on the Russian search for Hitler in 1945 on page 473: "A special team (of the Russians) quickly found Hitler’s body under a thin layer of soil. The Russian history expert, General B. S. Telpuchovskii, felt certain it was Hitler. The body was quite burned, but the head was intact, except for the back of the head, which was destroyed by a bullet. His teeth lay beside his head."

He continues: "But soon, uncertainty began to spread. More half-charred bodies were found; one looked like Hitler but had darned socks, and it wasn’t accepted as Hitler because we didn’t think the Führer of the Third Reich would wear darned socks! Then there was the body of a freshly fallen man, who had not been burned."

"Then two bodies resembling Hitler like twins (two doubles) were found. Hitler’s bodyguards and bunker staff were asked to identify the bodies, but no one could or would."

On page 474, he writes that the Russians showed Hitler’s dental assistant, Käthe Heusermann, Hitler’s lower jaw with a dental prosthesis for identification. She confirmed its authenticity. Shortly afterward, she was arrested and spent the next 11 years in solitary confinement in Russian prisons.

On page 475, Ryan writes, "What happened to Hitler's body? The Russians claim they burned it outside of Berlin, but they won’t say where. They further claim to have found Eva Braun’s body…"

In a footnote on page 475, he also mentions that the Russians remained silent to their Allies about the results of their Hitler investigation for over 18 years. The first proof of Hitler’s death from the Russian side came on April 17, 1963, when Marshal Vasili Sokolovskii confirmed it to Professor John Erickson (as fact?). Ryan, unfortunately, does not inform us which of the many "Hitler bodies" the Russians presented to us as the real one, given that even the Germans couldn’t distinguish them.

William Shirer, the infamous "Germany expert" who reports on Hitler’s table-pounding rages, writes in his book The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, published in New York in 1959, on page 1134: "Hitler's remains were never found, which gave rise to rumors that he had survived the war."

Another foreigner who has written extensively about Hitler also deserves mention. Alan Bullock, in his lengthy anti-German tome Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, writes on page 800 of his revised edition, published in New York in 1962: "It is absolutely true that no incontrovertible proof in the form of Hitler’s own dead body was ever produced."

Lieutenant Heimlich, an American Jew from the Counter Intelligence Corps tasked with investigating all traces of Hitler's disappearance, wrote several times in the U.S. magazine for amateur detectives with millions of copies, Police Gazette, about his investigations into Hitler's whereabouts: "There is no proof that Hitler really died! (There existed not one iota of proof that Hitler had actually died)."

In 1968, the Christian Wegner publishing house in Hamburg made headlines with the book by the Russian Jew Lev Bezymenski, The Death of Adolf Hitler*, which was later published in America under the title The Death of Adolf Hitler by Jove/HBJ Books, New York. The book is a typical piece of communist propaganda, vaguely hinting at an axis between fascism, capitalism, and NATO. It is evident that Hitler is being used here to bait the gullible. The Hitler now officially declared dead and dissected by the Russians (with one testicle) supposedly poisoned himself with cyanide. However, on page 96, we read that Günsche saw a gunshot wound in Hitler’s right temple. Linge, on the other hand, saw it in the left temple. Kempka saw it in the mouth.

Since cyanide acts instantly, it is impossible to first poison oneself and then shoot, as even the Russians admit that the dead do not shoot themselves. Therefore, one must assume that Hitler first shot himself in the temple, which again seems odd, as he was said to be trembling like a leaf the entire time. Afterward, he supposedly took the poison. However, Kempka claims that the Führer shot himself in the mouth, so after either killing himself with a head or throat shot, Hitler still had the presence of mind to quickly bite down on a cyanide capsule to ensure his death.

Even the most gullible contemporary would find this suspicious. Therefore, someone must be found to give the dead dictator the "coup de grâce" (the final shot). A few names are mentioned; now Hitler's greatest admirers and closest followers are being turned into accomplices or suicide assistants. On page 90 of The Death of Adolf Hitler, Adjutant Günsche, servant Linge, head of the bodyguard Rattenhuber, Führer-pilot Baur, and Reichsleiter Bormann are all suspected one after the other of having delivered the final shot to Hitler. In the end, Günsche and Linge remain. However, neither of the two later remembers which side of Hitler’s temple they saw the wound on, nor which side they themselves shot into for the coup de grâce. The Soviets still suspect Günsche to this day. On page 100, Professor Smolyaninov insists, "all speculation about gunshots is inconclusive, Hitler died from poison."

According to Father Lamb in his article "Hitler lives in Russia," the three main eyewitnesses changed the confessions they gave to the Russians after being released from imprisonment. Professor Dr. Wilton M. Krogman of the University of Pennsylvania proved that Hitler could not possibly have been burned in the way described by the eyewitnesses.

And to clear up all confusion, the head of the "Autopsy Commission, Chief Expert, Forensic Medicine, 1st Byelorussian Front, Medical Service, Lieutenant Colonel Dr. Faust Shkaravski," the man responsible to Stalin, also insists on page 100 that: "All imaginative reconstructions of a shooting" are nonsense. "The fact of poisoning is indisputably proven. No matter what is claimed today. Our commission could not find any trace of a gunshot wound in May 1945."

They couldn't make sense of Kempner's words back then, and certainly not today. To be honest, I don't fully understand what's going on here either, and I still can’t quite figure it out. But one thing I’ve learned in the past twenty years of political study is that when a Jew of the caliber of Robert Kempner makes such statements in public, we Germans should be on guard.

Of course, I’m personally interested in whether Hitler managed to escape in 1945. It would certainly be an adventurous story, detailing how it was accomplished, where the journey or flight led. What did Hitler do in exile? How long did he live? Did he ever return to Germany incognito? Or does he still live today?

Do you know where? Possibly in NeuSchwabenland.

What really happened in the world between 1946 and 1948? In Europe, it was a time of hysterical anti-German propaganda. It was the time of the war crimes trials, of arbitrariness by the victors, and of severe physical and emotional distress for vast segments of the German population. Numbed by the many shocking events, everyone fought for bare survival.

However, in the militarily victorious countries abroad, rumors of German submarines in South America were circulating, often substantiated by facts. For instance, the renowned French newspaper France Soir published a sensational article on September 25, 1946, about a German "phantom submarine": "Nearly 1-1/2 years after the end of hostilities in Europe..."

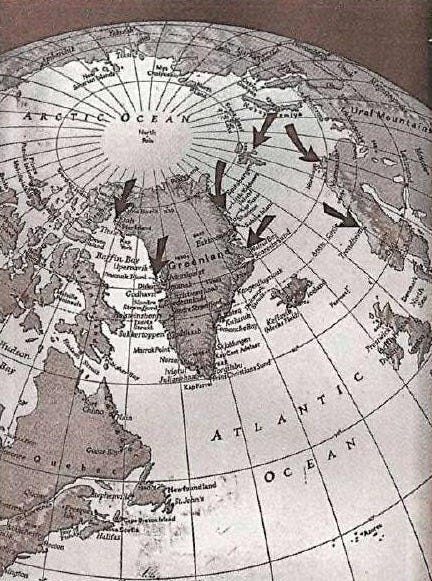

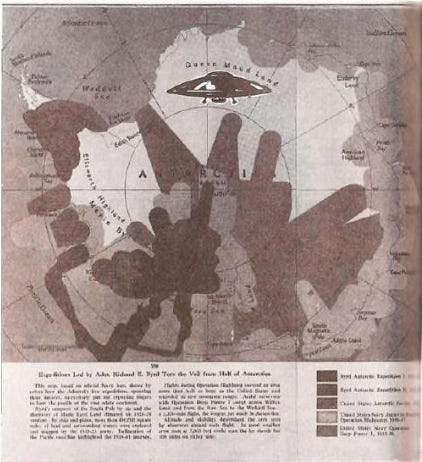

This prompted the Americans to decide to investigate these rumors. On the orders of U.S. Navy Secretary James V. Forrestal, they undertook the largest Antarctic expedition, officially named "Operation Highjump." In collaboration with U.S. Navy Fleet Chief Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Vice Admiral Forrest P. Sherman, and Rear Admiral Roscoe F. Good, the operation was swiftly implemented. Rear Admiral Richard H. Cruzen handled the detailed planning.

In his nearly 100-page report in National Geographic Magazine, Vol. XCII, No. 4, October 1947, about this U.S. expedition, the famous American Antarctic explorer Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, U.S.N. (Ret.), the actual leader of this largest expedition of all time, wrote that the U.S. Navy was unfortunately severely hindered because "this operation had to be hastily and hurriedly planned." (Page 430)

One might ask: Why did a supposedly scientific expedition have to be organized so hastily? Why the rush? Why the urgency?

It quickly became apparent why such haste was necessary. Shortly before his departure on December 2, 1946, Byrd assured attending reporters, "My expedition has a military character." The expedition participants consisted solely of 4,000 sailors and marines who carried provisions for eight months.

The fleet consisted of an impressive convoy in size and firepower. The lead ship was the Mount Olympus, with Rear Admiral Richard Byrd on board, accompanied by the icebreaker North Wind, the seaplane tender Pine Island, the destroyer Brownsen, the aircraft carrier Philippine Sea, the submarine Sennet, the icebreaker Burton Island, the two support ships Canistead and Capacan, as well as another seaplane tender, Currituck, and a second destroyer, Henderson.

On December 26, 1946, it was announced from England that a British-Norwegian expedition stationed in the polar waters of Bahia Marguerite was available to assist Byrd. Meanwhile, eight other nations, including Russia, were also engaged in "weather studies and climate questions" in Antarctica at the same time.

Although Europe, America, and Russia were already at military odds in the "Cold War," in Antarctica, they were suddenly united.

Byrd’s report is filled with numerous black-and-white and color photographs, all practically military in content, showing soldiers, tanks, snow tractors, bombers, helicopters, and so on.

Under the headline "Encirclement of a Continent Planned," Byrd wrote, on page 437, that his plan was to "attack" the continent from three fronts. On page 432, he claimed that under his leadership, a reconnaissance network would span the Antarctic continent within a few weeks. On page 434, he proposed planning a combined army and navy expedition for next time.

The expedition quickly became active after arriving in Antarctica. Amphibious tanks were landed, bulldozers and other tracked vehicles were unloaded, and with the stars and stripes fluttering, they sped inland through the snow. Where or against whom this was intended, the article does not mention.

However, it is interesting that Byrd's aircraft, in its attempt to reach the pole and fly over certain Antarctic areas, experienced engine failure (page 460). For unexplained reasons, the heating failed, the autopilot malfunctioned, the windows froze over rapidly, and the fuel in the tanks began to evaporate. The entire crew was threatened by oxygen deprivation, and they lost their sense of orientation.

Another aircraft flew into a weather front that resembled a large bowl of milk; there was no horizon, and the experienced pilots didn’t know where they were. None of them could tell whether it was fog, drizzle, water vapor, or snow. Shortly afterward, the plane crashed. Three crew members died when the aircraft exploded.

These and other accidents, along with the experience of simply not being able to break through to certain areas, led to the early termination of the expedition.

It should also be mentioned that on this "purely scientific" expedition, the press was heavily represented, with nine newspaper reporters, two radio commentators, and representatives of the three major news agencies: UPI, AP, and Reuters, as well as several people from the largest daily newspapers and major radio and television networks. But no purely scientific expedition to the eternal ice of the uninhabited Antarctic has ever attracted such "press interest." What news was expected down there?

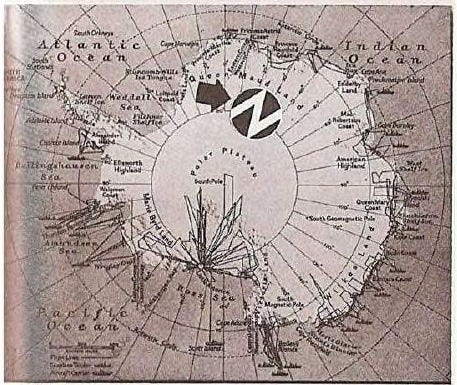

According to the Spanish book Hitler está vivo (Hitler is Alive), page 161, Admiral Byrd, when pressed by reporters, responded: "He was prepared to break and destroy Hitler’s last desperate stand if he managed to capture him in his 'New Berchtesgaden' within New Swabia, in Queen Maud Land!"

Admiral Byrd concludes his report with a warning to America to prepare for an imminent conflict in the polar regions, which he predicted would be of the utmost strategic importance as battlefields in future conflicts. (Page 520)

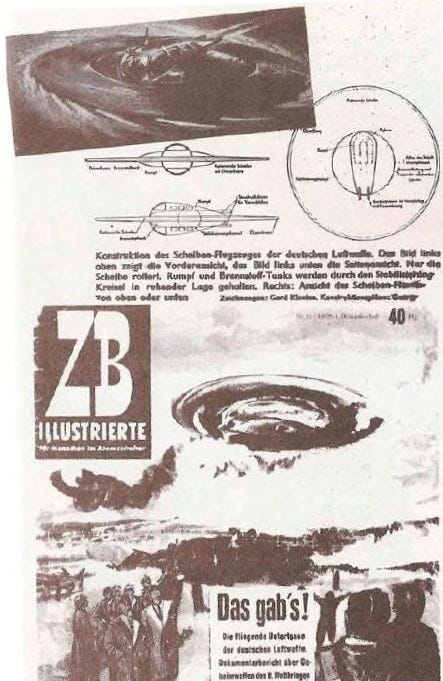

We leave it to our readers to draw their own conclusions from these thoughts, with one final reference from a book published in America. The authors of the book, a well-known Jewish writer couple, Ralph and Judy Blum, titled Beyond Earth, report an incident of great importance on page 65. An experienced pilot of the 415th Night Fighter Squadron was flying over Hagenau, Germany, at six in the morning on December 22, 1944. Suddenly, he and his co-pilot saw two large, orange, glowing discs rapidly rising from the ground towards them. As soon as the discs caught up with the American fighter plane, "the discs remained at the same altitude and followed me for two minutes through the most difficult flight maneuvers with perfect precision. After a few minutes, they turned away under perfect control and suddenly disappeared."

On page 67 of the same book, they include a report from the Technical Intelligence Division of the U.S. Strategic Air Force in London, 1944. "We received alarming reports from various sources that bombers returning from Germany increasingly complained about mysterious engine failures. Spies and German prisoners reported a mysterious weapon responsible for this.

"After extensive discussion among intelligence experts, we concluded that the Germans were using a new secret weapon that disrupted the electrical systems of our bombers. It gave us great concern because we knew it would take the entire electrical production of Europe to cause a short circuit in a B-29 engine. However, Germany had already lost Europe."

"A special aircraft was equipped with all kinds of measuring instruments. The pilot was a volunteer, and he returned from his mission like a madman. He raged, screamed, was furious and hysterical. No one could find out what had happened to him."

"The next day, he had forgotten everything. The instruments showed nothing. Later flights revealed nothing new."

Is it possible that Admiral Byrd and his pilots in Antarctica fell victim to such weapons? Admiral Byrd returned to America and was shortly afterward admitted to a naval hospital, where he never emerged alive. His papers and records are still treated as classified by the government and his family to this day.

Why? If these were merely scientific documents from a purely scientific expedition, why the secrecy? Or perhaps it wasn’t purely scientific after all?

Do you now know the solution to the mystery?

"Fireland" is the closest to the German territory in Antarctica. Could that have been Bormann’s destination on May 1, 1945?

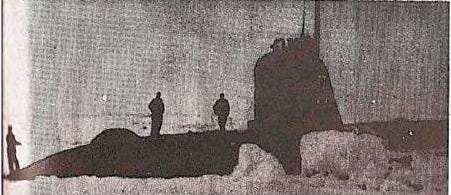

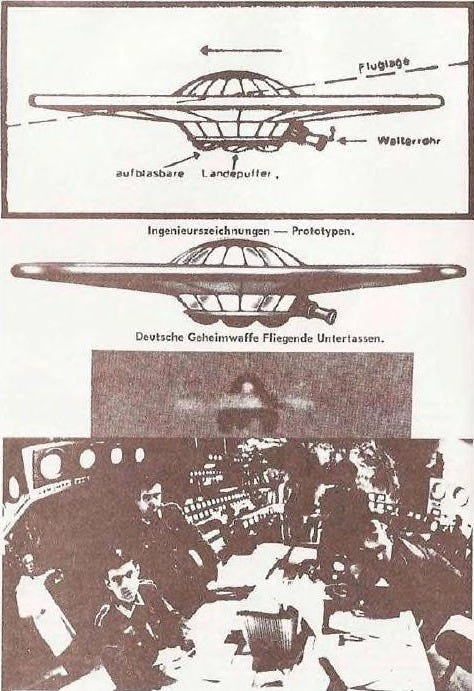

An American NATO reconnaissance aircraft, whose shadow can clearly be seen on the water, photographed an unknown submarine just diving. Compare again here the tower and the streamlined shape with the German designs from 1944-45.

Another submarine, without identifying marks, which surprised the Americans on the high seas. Hardly a month passes without sensational sightings of "phantom submarines."

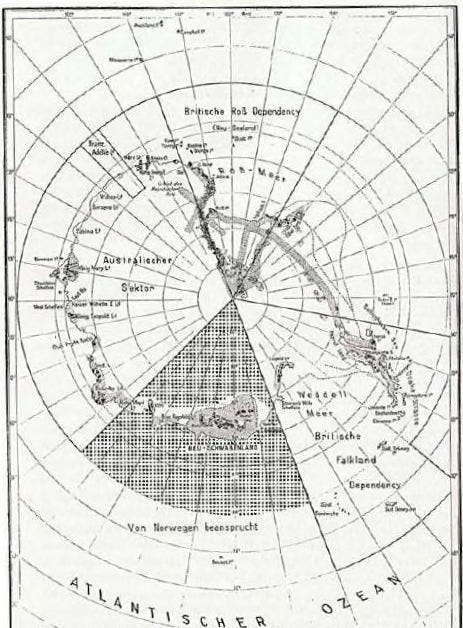

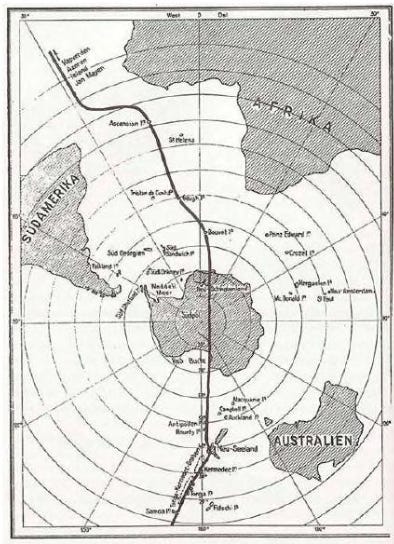

Before we now come to the super-secret weapons brought up by our opponents, the flying discs, etc., which caused the Allies so much trouble in the last months of the war, we want to briefly convince ourselves of the authenticity of the German Antarctic expedition, and thereby of the right of the Germans to large parts of Antarctica, with its abundant uranium, oil, coal, ores, and fishing grounds.

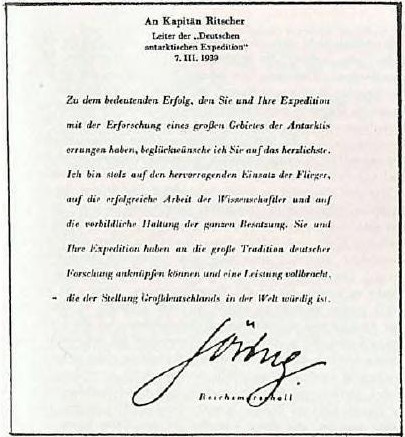

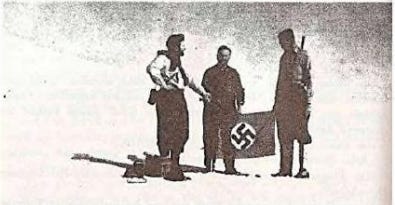

The report, the photos, and the drawings come from an interim report submitted to the Führer — all are genuine.

The badge specially created for the participants of the German Antarctic Expedition 1938-39 highlights the German claims by precisely indicating the area of the explored territory.

Introduction

This popular work on the German Antarctic Expedition of 1938/39 by Dr. Ernst Herrmann provides a vivid picture of both the course of the 117-day sea voyage, during which the expedition ship reached its working area at the end of the world in front of the ice-covered coast of the Antarctic continent and then returned to the homeland, as well as the multifaceted activities that stood out in the lives of the 82 expedition participants during that time.

The undertaking was commissioned by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, as commissioner for the Four-Year Plan of the German Reich. The aim was to continue earlier German exploratory work (e.g., E. v. Drygalski, W. Filchner) in those distant parts of the world, and at the same time to create a foothold to secure that Germany, alongside other major powers, would secure areas that could one day be of importance. A staff of experienced young scientists, accompanied by experts in transoceanic air traffic, was deployed for the scientific exploration. The Deutsche Lufthansa A.G. contributed personnel and an excellently organized radio crew to accompany the expedition. Captain Alfred Kottas of the expedition ship "Schwabenland," an air base of the D.L.H. for training air transport pilots, was assisted by the renowned whaling captain Otto Kraul as an advisor for ice guidance.

The fortunate circumstance that Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring had taken over the fundamental organization of the undertaking and placed it in the hands of his deputy and with expanding powers appointed Ministerial Director and former State Secretary H. Wohlthat, was to thank for the success of the expedition. State Secretary Wohlthat was the spiritual father of the expedition and its patron until the end. For the timely preparation of the ship, the necessary equipment with nautical instruments, the scientific and flight equipment for the research and the careful collaboration of the seamanship with the scientific staff of the Kriegsmarine, Luftwaffe, and the Ministry of Nutrition and Agriculture, as well as the Deutsche Luft Hansa A.G., the Deutsche Werft Hamburg, and the Norddeutsche Lloyd each provided invaluable assistance. The cooperation and the fortunate selection of participants corresponded to the results of the expedition. The tasks set for them were successfully completed in full.

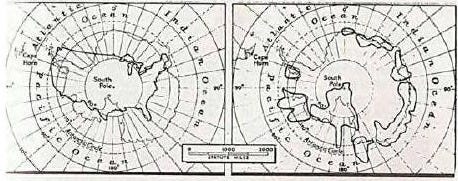

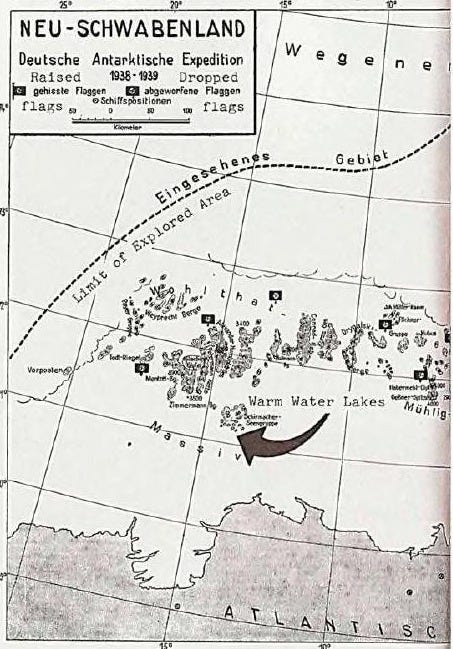

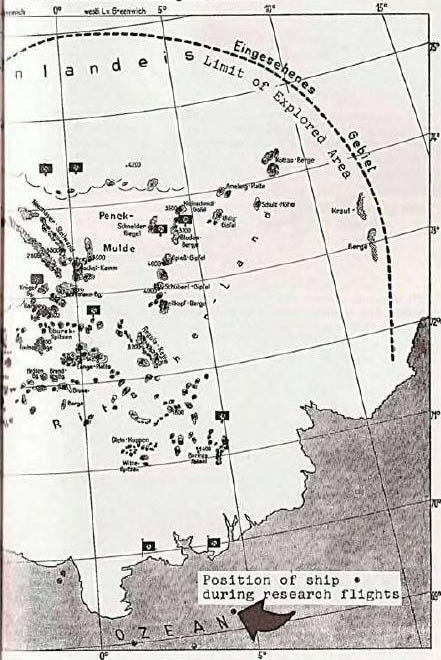

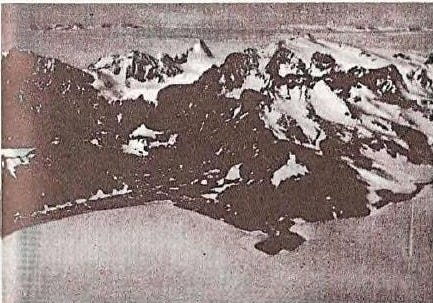

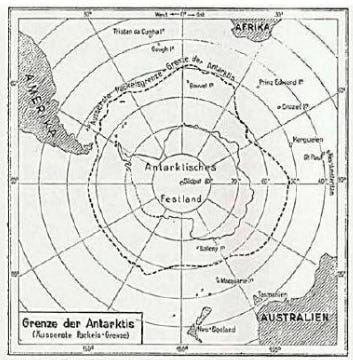

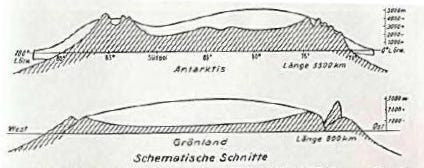

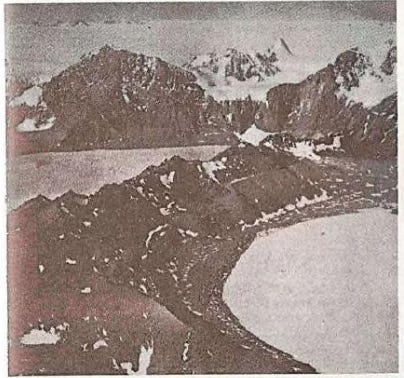

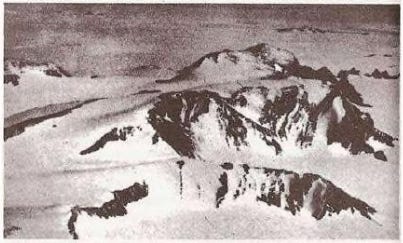

The publication of the scientific findings will be reserved for the scientific expedition work, the first volume of which is in the press and the second volume will be published after the war. The flight and air exploration success was recorded in the provisional overview map of the explored area included in the appendix, between 11½° W and 20° E and south to 76¼° S latitude, which was found in Antarctica. It has been named "Neu-Schwabenland" and covers an area of more than 600,000 square kilometers, consisting of terrain never seen by human eyes, with mountain ranges, some peaks reaching 4000 meters in height.

Although organic life in Antarctica is limited to the lower regions of the shores, there is an abundance of marine life, penguins, and seals, as well as many whales and other fish species that provide substantial food reserves. The vast, untouched snow-covered landscape, which appeared overwhelmingly impressive under the clear skies, left an unforgettable impression.

Whatever the eye sees, it is overwhelming, the endless expanse of the landscape, the indescribably clear air above the airport often allowing visibility of more than 200 km in all directions, with mountain ranges 200 to 400 km distant, whose pointed peaks reach heights of 4000 meters into the frosty sky. The wide, unbroken ice horizon that arches upwards in the distance, where the giant flat ice dome rises towards the Pole, pierced by storm systems typical of the polar world, unseen in any other place on Earth, painted in a brilliant array of colors, especially at sunrise and sunset.

The letters from expedition participants constantly showed me anew how great an experience the trip was for each of them. None would want to forget this, even if a return trip were to be considered one day.

A. Ritscher, Expedition Leader

Test Run

Do you know the noise of a steam hammer? Or have you ever been in a boiler forge? That's how you must imagine my first visit to our new expedition ship. A deafening noise, a crashing, clattering, screeching, whistling—Oops! The hat slips off your head, and you suddenly stumble into the dark. "Sorry! Excuse me!" One hears from a great distance, and when you manage to get your hat back on, you see that the man with the 5-meter-long beam on his shoulder is now paying attention again.

You see with some Schadenfreude that the man with the beam also bumps into other people. Then you get hit by a piece of iron. "Hey guys, you need to move, it's dangerous here. There’s a high-voltage line over there." With one jump, you're three steps to the side. Of course, you’re now standing in someone else's way again. You just shake your head. From this mess of iron plates, cables, beams, this almost unimaginable chaos, a ship is supposed to emerge in 14 days. At the moment, it looks like a scrap yard for all screws and junk ships.

We are all very curious to see which phoenix will rise from this pile of dirt and ashes. That is, we already know exactly! One is the chief engineer of the shipyard, and the other is the chief engineer Uhlig from the ship itself. These two men have undertaken the transformation. They stand there quietly and confidently in the midst of the chaos as if this were completely normal. The two know exactly what they are doing! And then no one on the ship believes anything is amiss, as the expedition leader seems to know what he’s doing, having supposedly consulted with all the gods of old and disassembled sewing machines, old plans, and crumpled measurement marks. He stands on top of all this and then makes a brilliant proposal—everything will be finished in two weeks. Also, one stumbles over all the cables, wires, and old screws, but one is grateful for them. Thank God! Thank God! The more wires there are, the more quickly people work, and the sooner the boat is finished and ready to go, the sooner we can depart... The expedition leader seems to believe in using unguarded words to praise all the old companions who were apparently bribed by him... and... indeed they achieved that the entire screw scrap was miraculously removed on the fourteenth day.

But as far as we know today, we fled from all the noise into the "salon," where, fortunately, not much was being riveted and welded, and the dents in our knee-high boots were beaten out again. Along the way, one curses a bit, but then looks at each other in the dim light with Kraul, Pregula, Amelang, and their respective subordinates. With a slight friendly smile, one recognizes each other, as if seeing an old friend in the underground. What is one supposed to say to Mr. X. or Mr. Y. What did the inexperienced man say, the name "Kraul"? It wasn't until 8 days later that we realized that it should actually be "His Majesty" Kraul, as the first person had to learn. But more about that later.

First, the expedition leader, Captain Ritscher, welcomes us all and introduces the expedition plan for the first time aboard the "Schwabenland," the ship that will take us to the Antarctic continent.

At this first meeting, six scientists, the pilots, and all the ship's officers and engineers participate. It is good to hear about the full scope of this well-equipped expedition with the most modern research tools. Each of us knows only a narrow area of our field.

I look at the individual faces, and I can see on each one how a sense of pride and joy rises in them, being part of such a grand undertaking.

Captain Ritscher finishes, and there is a glimmer in his eyes, a joy in leading an undertaking that has significance for the future. The rest of us, too, are excited to be part of something much larger than any of us. Perhaps we will discover something new about the world and, who knows, maybe even change it. I leave with the thought that this expedition might be one of the greatest events in my life, one that I will always remember.

Fourteen days later, the "Schwabenland" is scheduled for its test run. The German shipyard has invited 50 prominent figures, including all the gentlemen from the ministry. No women! Women do not belong in this prominent circle. Even the stewards know the decorum. Every "Dr." today is at least a professor or secret councilor. If he wears a sailor's cap, then he is an admiral.

The weather is not bad; it is not too hot, so it is worth lounging on deck in a deck chair, but unfortunately, there are no chairs available. Even if we had deck chairs, there would be work to do. In addition to everything else, Dr. Todt, the secretary of the expedition, makes a timid attempt to store hundreds of boxes and crates on the ship. No one knows what's inside them, but we are sure that the expedition will manage, even with these unexpected shipments. With a bit of luck, at least some of us might be able to open the first boxes and see what's inside.

Meanwhile, all sorts of meetings are taking place. That's why the gentlemen from the ministries have come, after all. They have some important special requests, mostly for more funding, and they want to see how their money has been spent. The heads of the various scientific institutes also have special requests. Some even receive free refresher courses. There stands Dr. Regula, the meteorologist, blowing into his wind gauge to simulate a 25-meter storm for a finance official. When the finance official blows back into the gauge, he is praised: "Yes, you're doing just fine!"

This is no ordinary expedition! Anyone who did not realize that before can see it now, surrounded by the invited dignitaries, hearing all the formal and special requests. An assistant stumbles and asks: "Are we really going to the South Pole?"

"So? Tell us more about that."

And now, gentlemen, in conclusion, as participants of the German Antarctic Expedition of 1938/39, which, after 26 years, will again try to gather valuable scientific knowledge in this still largely unknown territory, I wish you and our esteemed expedition leader the best of health and work power. Return home safely and bring back excellent results. Heil Hitler!"

These were the parting words of Ministerial Director Wohlthat, the spiritual father of the expedition, after he had gone over all the scientific special tasks with each of us.

After the train journey from Cuxhaven to Hamburg, we had one more opportunity to receive valuable advice from the knowledgeable scientists.

Departure

The "Schwabenland" is now fully prepared for departure. The chief engineer, now called the "chief," is already standing, ready to switch on the diesel engine. But have you ever seen a sailor with a Friday departure phobia? Well, that’s not happening here. So we’ll spend the whole day onshore, finishing up the last little things before we depart.

Now, here we go! The tugboat honks, and slowly our 8000-ton ship moves down the Elbe. When we round the corner near Cuxhaven, we set a direct course for the South Pole, nearly reaching 70 degrees south latitude. The German Antarctic Expedition 1938/39 is now on its way to its destination.

It's getting warmer, day by day. Today, December 21, we pass Cape Finisterre. So, Spain is behind us. A few hundred kilometers inland, people are fighting. Aircraft are dropping 500-kilo bombs on age-old buildings. You are reminded of Fontane's bridge over the river Tay: "Death and the land, the waves of the sea, do not care about the fight above."

We focus on our mission, testing our modern scientific instruments and equipment, trying out new and unknown territories. With Paulsen, the oceanographer, and Braun, the electrician, we get to work on the sounder, measuring the ocean depths. We compare our readings with the nautical charts, and everything seems fine. Each sounding brings back accurate results, which we will later verify with over 6000 data points!

The invention of the sounder is credited to the German engineer Alfred Behm from Kiel. He was the first to think of using underwater sound detection in a new way, which was later implemented during the World War. He managed to measure sea depths using sound. The sound waves bounce off the ocean floor and are detected by a microphone. The time it takes for the echo to return is used to calculate the depth. For instance, if it takes 7 seconds for the echo to return, with sound traveling at 1500 meters per second in water, you can calculate the depth as 5250 meters.

The most important thing is the accuracy of the measurement, which takes less than 7 seconds. Every deviation, whether from water temperature or salinity, is accounted for in the results. We recently discovered that our wire got tangled at 4127.63 meters, nearly causing the oceanographer to be lynched!

Christmas — New Year

On December 22, we pass Cape Roca, the entrance to Lisbon. The weather is as wonderful as ever.

Our electricians have set up a loudspeaker system, and Reich Minister Hess's Christmas speech reaches us even under the Canary Islands. Unfortunately, we have to cut the broadcast short due to atmospheric disturbances. Our second officer, Röbke, leads us as the political officer of the "Schwabenland" with a final "Sieg Heil" to the Führer and the Reich as we celebrate the holiday onboard.

Captain Ritscher follows with a Christmas story, his own. For 26 years, he has celebrated "Christmas Eve" either in ice or snow, something unfamiliar to those who have never experienced it. He tells us what it is like to celebrate Christmas surrounded by snow and ice, setting the tone for our introduction to the Antarctic expedition.

In 1912, Captain Ritscher had the nautical command of the ship "Herzog Ernst," which brought the "German Arctic Expedition" from Schröder-Stranz to the northern coast of Spitzbergen. A series of unfortunate coincidences, financial difficulties, and so on had caused a very late departure for the expedition. Summer came to an end too quickly, autumn lasted only a few days in these latitudes, and winter surprised them, trapping the ship in ice. Since this is the account Captain Ritscher retold, I will recount the whole story of the fear surrounding the ship, the division of the expedition into different groups, one of which perished, and Ritscher’s own march from Schröder-Stranz with three companions in the wild northern part of Spitzbergen, in North-East Land. One group of eight men, under Captain Ritscher’s command, remained from September until December in an abandoned trapper’s hut on Petermann’s Cape near Wijdefjorden. They lacked food and ammunition and could not shoot even a single bird for weeks. They survived by rationing their last provisions. By early December, Ritscher set off alone on foot with his dog Bella to reach the nearest settlement of Longyearbyen. He didn’t know if he would make it, but he walked every day and every night. He had no tent, no map, no cooker, no pot, and not even a piece of bread. He walked and walked... it was a fight for life, a fight of one life against the other. His dog Bella stayed with him, his consolation and comrade. Sometimes she would walk ahead, as if she had scented a fox, but then she would return, too weak to catch any game. Temperatures of minus 30 degrees Celsius meant it was always night. He couldn’t see the moon or stars, just the blackness overhead. For nine days and nights, without eating, he continued. He felt more like a machine than a human, and Bella’s soft footfalls echoed, "trab, trab, trab."

The machine keeps walking, the body too numb to know when to stop. But Ritscher found reserves of strength and moved onward. Ridiculous, he thought, how the body simply must go on, and he went on, step after step, southward, ever southward. Away from the pole star above, through the cold, not toward the North Pole but away, toward warmth. Maybe he would reach the tropics, he thought absurdly, as his body continued, conserving strength, walking mechanically, feeling the first signs of madness creeping in. He began to laugh at his own ridiculousness, but still, he walked.

Ritscher invented a trick: he would lie down, rest his head on his hand, and tick off the minutes on a pocket watch. He slept for 15 minutes, waking when the alarm sounded. This trick helped him avoid freezing, and after a few hours, he would rest again. And Bella kept walking beside him.

Finally, Cape Thordsen came into view. The ice fjord stretched ahead, and on the far side lay the settlement. But the fjord was 25 kilometers wide, and the ice wasn’t fully frozen. It was Christmas Eve. They had waited, hoping the water would freeze solid. By now, Ritscher was ravenous, the hunger unbearable, but still, he marched. Bella walked beside him.

A favorable wind came up, and the ice began to solidify. Ritscher jumped from floe to floe, running southward again. At one point, he fell into the icy water but climbed back out. His clothing, boots, and gloves were soaked. Now walking was no longer fun; it became deadly serious. He continued in a frenzy of fear, until finally, on December 27, he reached the settlement. And Bella was still with him.

The experiences were hard, costing him several toes and fingers to frostbite. But within days, Captain Ritscher led a rescue expedition back to Schröder-Stranz to save the rest of his party, including the group at North-East Land. Everyone was saved except for the Schröder-Stranz group. Even the ship was salvaged.

Captain Ritscher reflected on the joy and relief of that rescue, the sense of triumph. As he recounted the events, we all realized he was no newcomer to the ice and snow. He had been through bitter trials and emerged with life.